In our family, to think of Roger Federer as anything but the greatest player in the history of the game of tennis is nothing short of heresy; to extol his virtues would be like trying to fit one more angel on the head of a pin. And this was it, Federer versus Robin Soderling at the 2009 French Open, a historical event on par with witnessing Lord Nelson versus Napoleon at Trafalgar, Henry V versus Charles d'Albret at Agincourt. Now, Federer's grail, his first win at the French Open, lay in sight, and with that victory, a chance at canonization like Saint Sampras before him. The red clay at Roland Garros never looked so promising.

And then, during the second set, with Soderling to serve, a man wearing a red shirt leaped from the bleachers and descended onto the court and ran up to Federer and put a hat on our hero's head. My father was following the match on a very high-definition television, a device which renders all sporting events and nature shows so immediate that 15 minutes in, I get a headache and have to remove my glasses. Thus, I was in the next room, watching on a far less resolute screen, as security guards chased down the spectator. Then a more familiar disruption of play took place: The phone rang. After years of such calls, I already knew who it was, and already knew not to pick up the phone.

My father answered. I could hear him as he spoke with clipped yet patient pauses between his sentences. "They've stopped play. A spectator's run onto the court. Yes, you heard correctly. He's carrying a flag. No, not Soderling or Federer. Darling, the spectator! It's a red flag. Moderately sized. About a foot by a foot and a half. He's run to the other side. Now they're carrying him off. No, I do not know which country has a red flag."

Roughly five games into any Grand Slam match -- especially during the finals, but sometimes as early as the qualifiers -- one of our phones will ring, and my mother will be on the other end, calling from some far away country (or as close as the living-room), wanting our take on the play-by-play. My father is the most patient of us, though we have all taken our turns, narrating tie-breakers and describing volleys, drop-shots, facial expressions, doing our best to channel our inner Patrick McEnroes, our voices tinged with mild-to-moderate annoyance. This time, my mother was in Italy with my sister, and had been calling home on five-minute intervals for the latest news from Roland Garros.

I'm not sure when I became aware that tennis was something more than a game to our family, but if I were to point to a beginning of our family's tale, it would be the afternoon, many years ago, that a 22-year-old woman went for tea at the President's Hotel in Cape Town. A young doctor, formerly of the Royal Air Force, was at the next table. They struck up a conversation, and he asked her if she played tennis. Though she was already a top junior player in her country, she responded with a casual nod. A match was set for the following day.

And so, my parents' first date was played over a game of tennis, where my mother beat my father 6-0, 6-0, 6-0. They were engaged two weeks later, and in their many decades of marriage, the only time my father took a set off my mother was on February 25, 1981. (We know the date because she was eight and a half months pregnant, and I was born the next day.)

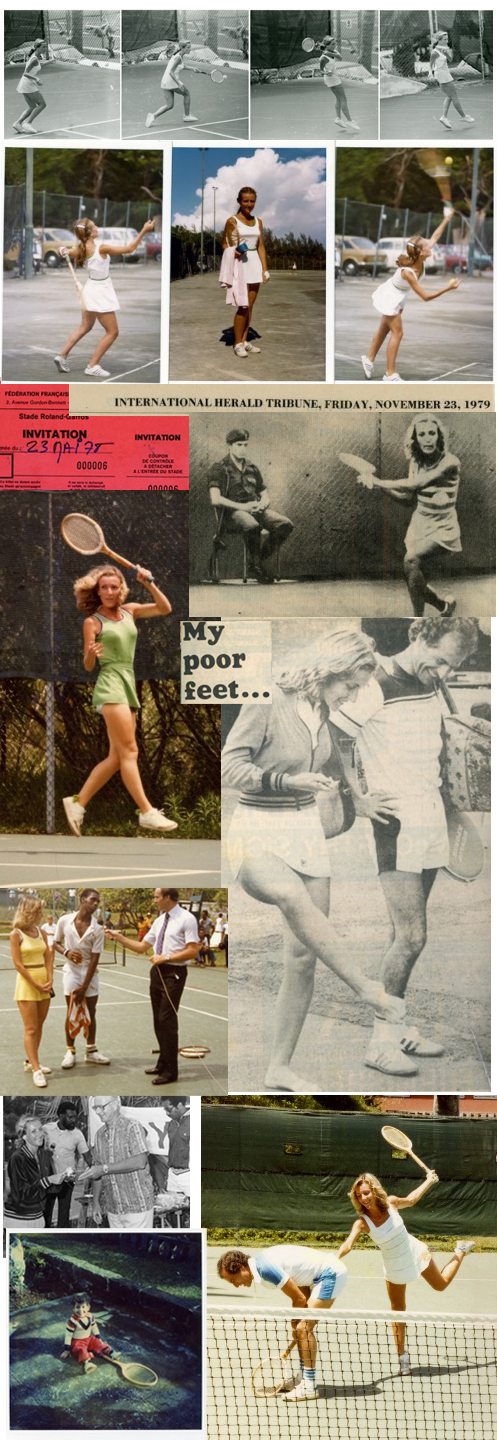

Our family scrapbooks are filled with old photographs and yellowing newspaper clips and other apocrypha from those early years. There's my mother's invitation from the Federation Française de Tennis, marked with a 23 Mai 1978 court date at Roland Garros, and another clip telling me that she lost 6-1, 6-1 to Great Britain's Anne Hobbs in the qualifying rounds. A few years later, there were the qualifiers at Wimbledon, another shot at the French Open, a round at the Scottish Open, and a trip to the Bahamas Open. One of her most impressive clips came from November 23, 1979 (see below), when she was playing in the Hansa International Tennis Tournament in Windhoek, Namibia -- not the safest of places back then. Soldiers armed with rifles served as the linesmen on center court. An Associated Press photographer snapped some shots of the match, and one of these pictures appeared in the International Herald Tribune. The soldier armed with the rifle seems to be mildly bored, whereas my mother's sliced backhand looks ferocious. (I still wonder how many soldiers qualify as International Tennis Federation line judges.)

It could be said that for a time our lives were demarcated by the baselines and sidelines of tennis courts, the images I have of my parents being forever linked with the game -- my father's striped Sergio Tacchini shirt-shorts-socks combinations, and my mother's Fila tennis uniforms, socks with little pom-poms on the heel, and white Adidas sneakers with powder blue stripes. This was her golden era of tennis, when she entered and exited the court in full make-up -- pink nail polish with matching lipstick, the preternaturally turquoise eye-shadow that she didn't give up until the early 90s -- and feathered blond hair, the likes of which hasn't been seen since Charlie's Angels went off the air.

Alas, though I enjoyed playing, I had inherited the Marks family rib cage, an anatomical trait that my father credits with saving his life when a bomb tore through his house during the blitz -- good for defending oneself against aerial attacks, but not so great for attacking one's opponents with drop-shots. My volleys were clubfooted and my serves were lopsided and flimsy. I had a series of tennis coaches who, as I like to imagine it, were the collective inspiration for Uma Thurman's sensei in the Kill Bill series. But this didn't help. No amount of time spent on the courts -- or running around them, or falling down upon them -- would ever make me a medal winner, allowing for my early yet graceful bow-out from competitive play.

We stole onto the courts less frequently, our games having already entered a phase that my mother called, in her spirit of understated euphemism, "a period of serious decline." We could play, but our lusty sinews weren't quite so lusty anymore. The only time I wore tennis clothes was when I fished out my father's old Lacoste tennis shorts and Rod Laver sneakers for Halloween, my go-to costume for the past several years.

Tennis still produced a whole range of emotions -- jumping, yelling, crying, throwing -- that came to a head each summer with the Grand Slam Season, watched on our old Sony front projection television. This was when networks would still do unthinkable things, like interrupt a match for Saturday morning cartoons, or presidential addresses. Players started using graphite racquets, and punctuated their volleys with -- horror of horrors -- audible grunting. Soon, they strode onto the courts in tennis uniforms of fluorescent pink, neon green, electric orange -- sacrilegious hues, in that the players wore vestments of something other than white.

As the years passed, modern technology finally caught up with our fervor. We replaced the projection television, and full-on tennis networks could be found among the many hundred cable channel that piped through our home. Unfortunately, another implement of modern technology soon started to interrupt the day's proceedings -- my mother's mobile phone, and her feverous usage of it, especially during match play.

The first and last time I narrated a match was the 2007 Australian Open's Women's Finals, Serena Williams' comeback, after a year spent on the sidelines, against Maria Sharapova. I was watching the match at a friend's house, vaguely unaware that my mother and father were in the airport lounge at Frankfurt Airport, waiting for their flight back home. For some inexplicable reason, the German television station cut from the live coverage.

And so, for the first time of many, my phone rang. Not knowing what was to come, I picked up. Thus began the match volleyed back and forth on our cell phones. How's one supposed to detail returns and slices and backhands, let alone enjoy the game, when Serena's serving so fast? I narrated a good portion of the second set to my mother, through her many questions -- "How high did she serve? Where were her feet? How was her landing?" -- and then swore that I'd never again pick up my phone during a game.

Federer won the French Open, the summer of 2009 progressed, and the play switched from the clay courts of Roland Garros to the grass courts of Wimbledon; Federer now had a chance at besting Sampras' record. I returned to New York to teach a pre-college course up at Columbia and spent most of my spare time in front of my television, for the summer of 2009 had not just been a summer of tennis. It had also been a summer of financial downturn and oppressive heat, of personal uncertainty and earnest longings, of shattering, unexpected miseries. Thankfully, there was now the calming, metronomic rhythm of a yellow ball being played across the lawns at Wimbledon, and the ascension of our hero Federer, higher and higher and higher.

Perhaps on account of this trance, I hadn't noticed an odd calendar glitch, that I had a class scheduled on June 7, the day of the Men's Finals, of Andy Rodick versus Federer. On that day, I watched the television while I showered, while I dressed, while I gathered my notes. The sets progressed endlessly, one onto the next, and into a fifth set, and into a seemingly eternal tie-breaker. I waited until the last possible moment, and then the next last possible moment, and then the next, and the next, before sprinting from my apartment and away from that match, already nearing its fourth hour.

As I ran to the subway station, I called my parents, for I knew they would be sitting at home, and I knew that they would be watching on that very high-definition television, and that they would, as parents sometimes know they must do, stay on the phone with their son. My mother picked up. Without saying much of anything, she understood what needed to be done. Across the several avenues I scrambled on foot, she detailed the snap of Rodick's spring-trap serves, the force of Federer's one-handed backhands -- patiently, intricately. And then, when I descended the subway stairs and into the darkened tunnels of limited-cell-phone-reception, my father started sending me updates by text message, on the off-chance that I'd receive any news from the courts.

Sitting on that train, waiting to find out if Federer had won, my thoughts of the match stopped for a moment, and for some reason, I began to consider the images in our old album, that the woman leaping through the air like a gazelle is my mother, and that I was once smaller than a wooden Dunlop racquet, and that Federer would set new records, and that he, like the greatest of the greats before him, would one day retire, and that I -- at that moment, on that train -- was several months older than my mother was when she bore me. The passage of time suddenly became all the more palpable; trivial things began to take on seemingly universal scope.

To some, no matter how powerfully or gracefully it's done, tennis will always be the simple act of bouncing a little yellow ball off of catgut and across a 78 foot expanse. But to a few of us, tennis is more than just tennis. It is the otherworldliness of the words and images in our old photograph albums, the way that ages and dates and time start to roil around in our heads. It's the returning to our memories, now and again, willfully forgetting the calluses and the blisters we have caused one another, and indeed, being thankful for them, for they are the meager price we pay for having played at all. It's the great swelling of emotion that crowds over us when we think back to the times we have spent on the courts, and the gratefulness we feel to have enjoyed them. But we all grow older; we all, at some point nearer than we could ever predict, must leave the courts.

And so, perhaps it's the thought that tennis could be more than just tennis, that it could be some timeless, ageless place, where we might flit about on courts unseen, our serves and our volleys forever bathed in that sun before the dusky twilight, where we remain young and agile and at the height of our games, and where, but for a still while, we are with the ones we love -- always, always. But until such a time, at least we still have the clay of Roland Garros, the grass of Wimbledon, the hard courts of Melbourne Park, and the greens of Arthur Ashe Stadium -- both on the television and over the phone.

(By the time I exited the subway station at 116th Street, Federer had won.)