Before vampires swooped into popular culture and satiated our appetite for sexualized supernatural characters, there was a time when witches, witchcraft and general feminine maleficium held a prominent place in our hearts.

Our collective obsession with witches has been exaggerated over the years thanks to the literature, film and television shows that gave us the Weird Sisters, the Wicked Witch of the West and Sabrina the Teenage Witch. Whether we feared them, envied them or were utterly enchanted by them, witches held the attention of readers and cinephiles for as long as the media existed.

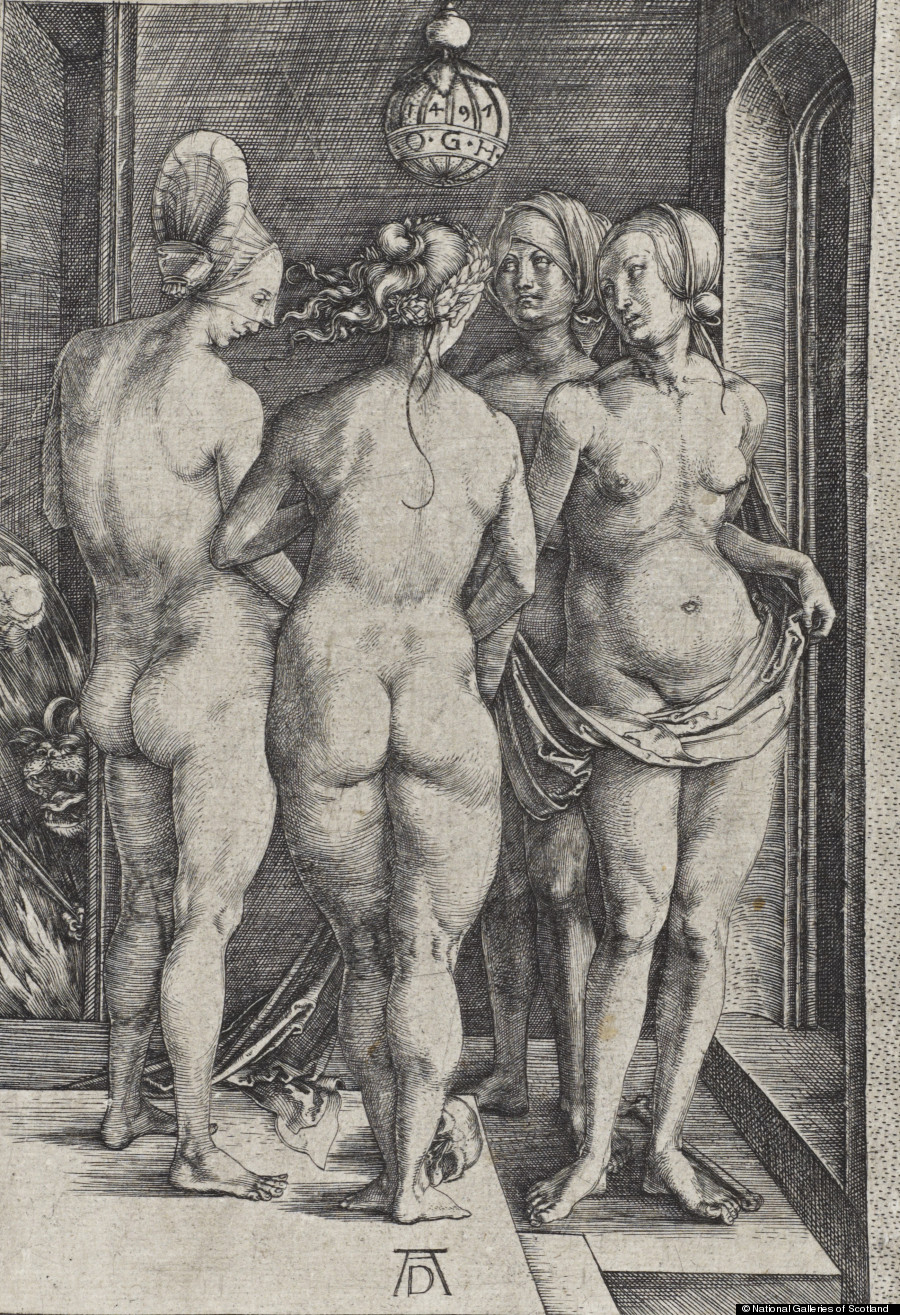

The art world has certainly played a role over the last few centuries too, amping up our fear and infatuation with wicked women. For over 500 years, artists from Albrecht Dürer to Cindy Sherman have had an indissoluble fascination with the phenomenon of witches. Art history anthologies are filled with images of female characters endowed with magical, sometimes malevolent abilities, echoing the general long-lasting cultural obsession.

Henry Fuseli, Three Weird Sisters from Macbeth, 1785, Mezzotint on paper 457 mm × 558 mm, © British Museum

A new exhibit at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, aptly titled exhibition, "Witches & Wicked Bodies," is paying homage to art's heated affair with witches. The show dives into darker depictions of witches hidden in prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures and more, shedding light on attitudes perpetuated by everyone from Francisco de Goya to Paula Rego.

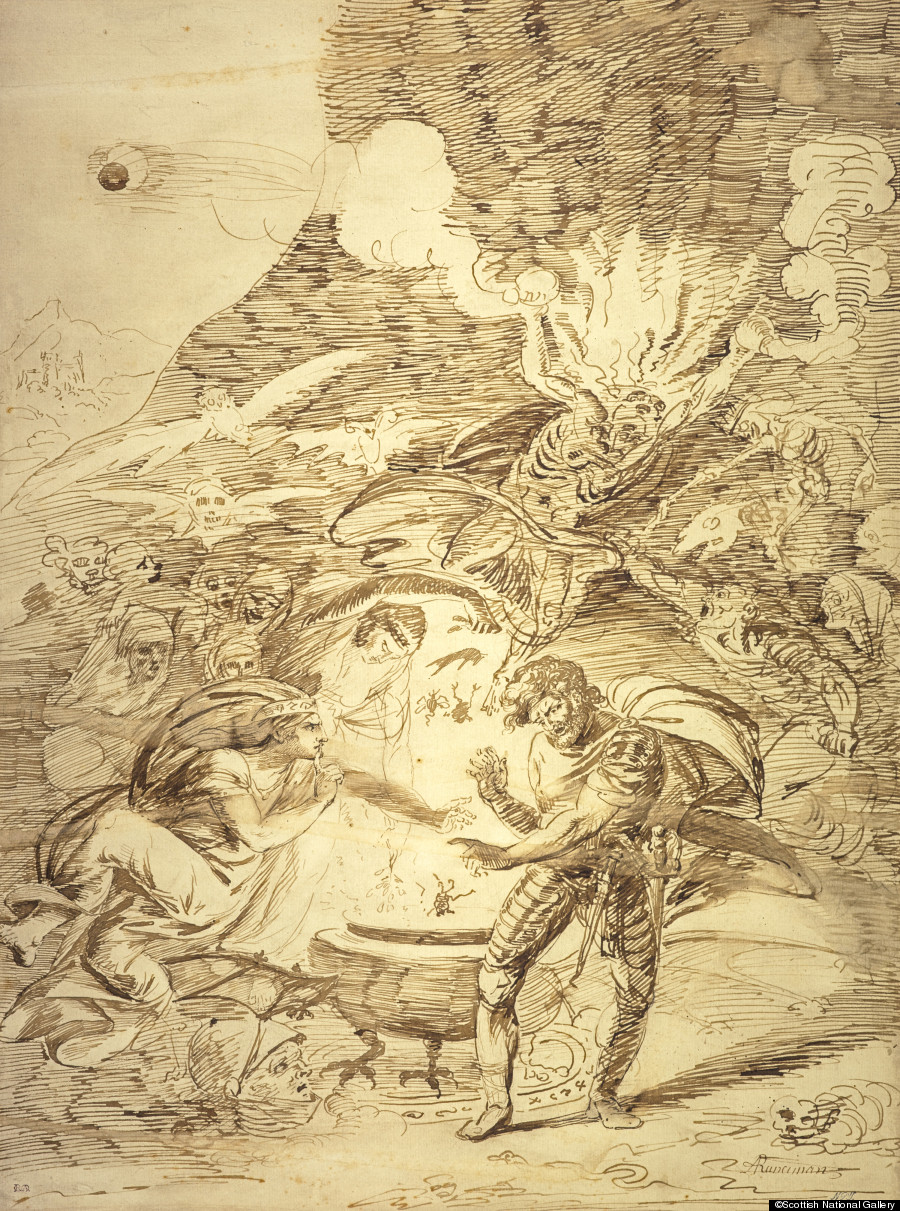

Across the extensive survey, seductive sirens are situated next to dowdy hags, as artists ogle and revel in the witch archetype. For artists like William Blake, Albrecht Dürer and Salvator Rosa, their witchy representations also act as reflections of their artistic moment. Blake pointed a finger at the moral hypocrisy of 18th century Britain with his "Whore of Babylon," while Rosa painted the late night séances that mystified even the cultured intellectuals of the 1600s. The works offer a glimpse into the paranoia and hysteria embedded in high European culture, when woman were tortured and executed for garnering the loose label of "witch."

William Blake, The Whore of Babylon, 1809, Pen and black ink and water colours, 266 x 223 mm, © The Trustees of the British Museum

Salvator Rosa (1615 – 1673), Witches at their Incantations (Scene of Witchcraft) c. 1646, Oil on canvas, 72.5 × 132.5cm, © National Gallery, London

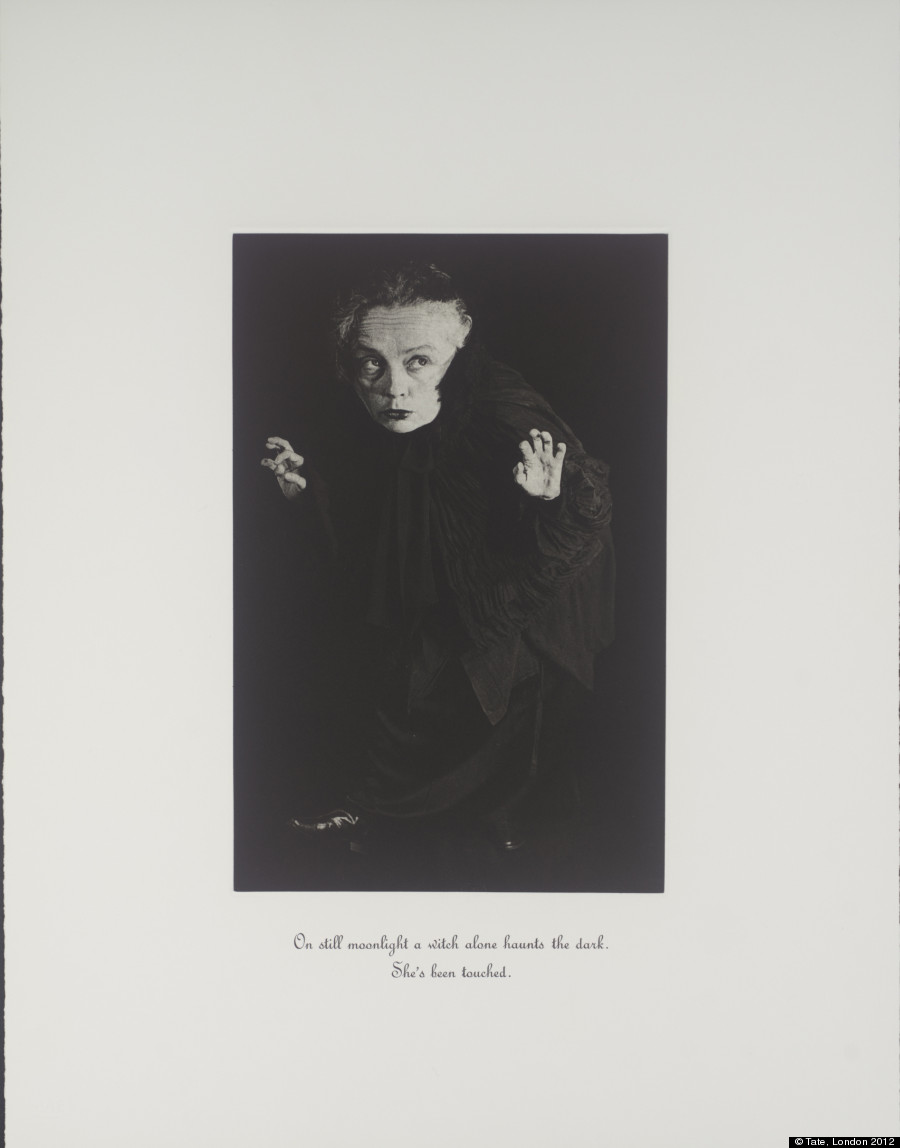

For more contemporary artists like Kiki Smith and Cindy Sherman, the image of the witch becomes a tool for reappropriating the feminine image; turning decades upon decades of female misconception on its head. How do viewers respond when it's not a male but a female artist framing the enchantress? And in the case of Smith and Sherman, self-identifying as "witch" by placing their own likenesses in the bodies of hags and vamps?

Kiki Smith, from Out of the Woods, Untitled (Encryption) 1:5, 2002, Photo-etching on paper: 290 x 190 mm, © Tate, London 2012

However if you're looking for the palatable sex appeal contemporary vampire sagas have delivered, you won't find it at the modern art museum. "Sexuality is key to our fascination with witchcraft, but this rather genteel exhibition denies us a wild ride with the temptresses," Jonathan Jones notes in an article for The Guardian.

Instead, the show of witches through the art ages is for the history nerds and literature buffs who recognize the tropes and characters painted by greats like Goya, Blake, et al. Though, it's safe to say fans of the Blair Witch Project and Witches of Eastwick alike will find something appealing to feast their eyes on here as well.

Scroll through the images below for a peek at the 500-year survey called "Witches & Wicked Bodies" and let us know your thoughts on the exhibit in the comments.

John William Waterhouse, The Magic Circle, 1886, © Tate, London, Oil paint on canvas 1829 x 1270 mm

The Four Witches (Bartsch No. 75 (89), Dürer, Engraving on paper 19.00 x 13.10 cm, © National Galleries of Scotland

Frans Francken II, Witches' Sabbath, 1606, Oil on oak panel, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Alexander Runciman, The Witches Showing Macbeth the Apparitions (about 1771, 1772), Pen and brown ink on paper 61.20 x 45.80 cm (framed: 84.50 x 59.10 x 2.50 cm), © National Galleries of Scotland

The Witches Rout (The Carcass), Agostino Veneziano; after Raphael (Rafaello Santi), Engraving on paper 30.70 x 64.80 cm (framed: 90.20 x 74.20 x 7.80 cm), © National Galleries of Scotland

Woman Bewitched by the Moon No. 2 [Opus 0.175], 1956, Alan Davie, Oil on Masonite, 152.80 x 122.00 cm, © National Galleries of Scotland

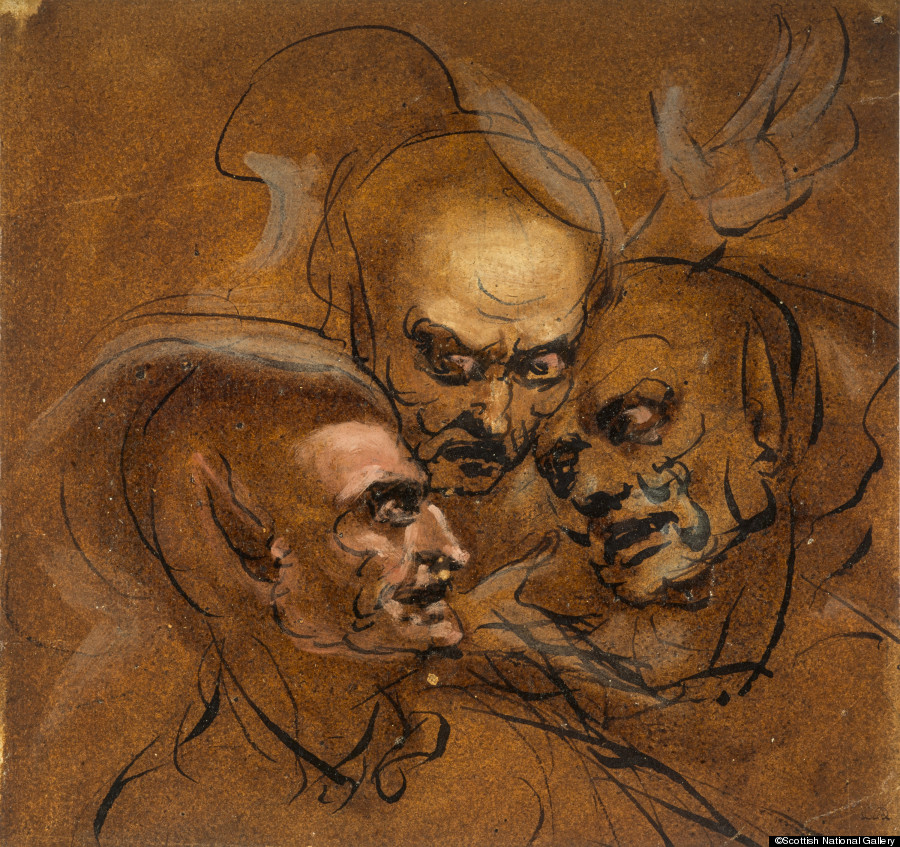

John Runciman, Study of Three Satyrs Heads, Ink and bodycolour on prepared paper 23.50 x 24.90 cm, ©Scottish National Gallery

The Triple Hecate c 1795, William Blake, Polytype on paper 41.60 x 56.10 cm, © National Galleries of Scotland

John Martin, Macbeth, about 1820, Oil on canvas framed: 86.00 x 65.10 x 7.60 cm, ©National Galleries of Scotland

Faust in the Witch's Kitchen 1848, Sir Joseph Noel Paton, Pen, brown ink and wash on paper 24.00 x 29.90 cm, © National Galleries of Scotland

After Jacques de Gheyn II (1565-1629); engraved by Zacharias Dolendo (1561 – c. 1600), Invidia (Envy) 1596-7, Engraving 22.7 × 16.5cm, © Trustees of the British Museum, London

L'Appel de la Nuit [The Call of the Night] 1938, Paul Delvaux, Oil on canvas 110.00 x 145.00 cm, © National Galleries of Scotland

"Witches & Wicked Bodies" will be on view at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art until November 3, 2013.