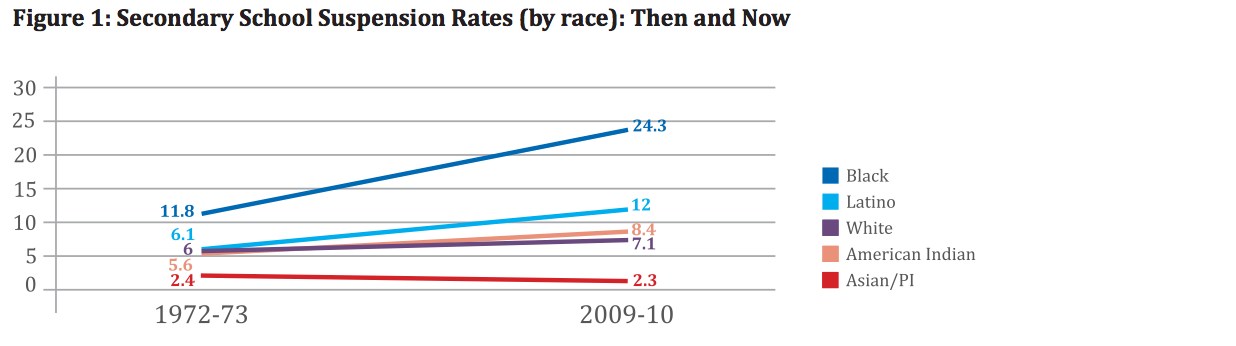

When you see school discipline numbers like these:

- 1 out of 9 students, including 36 percent of all male African-American middle and high school students with disabilities were suspended at least once during the 2009-2010 school year.

- 519 middle and high schools in the U.S. suspended half or more of their students in that year .

- 6,957 of U.S. middle and high schools suspended at least 25 percent of their students who were part of one of these groups -- ethnic minorities, English learners or students with disabilities.

And, in the same report, Out of School and Off Track, issued yesterday by The Civil Rights Project at the University of California-Los Angeles, you see this:

- 7,710 middle and high schools suspended 10 percent or less of any of their students in those subgroups.

- In Los Angeles, 54 schools suspended 25 percent or more of minority students, those with disabilities or English learners.

- And at the same time, 81 other schools in Los Angeles suspended 10 percent or less of students in those subgroups.

Then it's clear that the schools that have a high number of suspensions and carry out disproportionate suspensions of minorities, students with disabilities and English learners no longer have much of a reason or an excuse for doing so.

The heavy-hitting report underlines findings from previous reports that expose how suspensions fill the school-to-prison pipeline. It goes into great detail, demonstrating clearly that school suspensions -- 95 percent of suspensions are for "disruptive" or "willful" behavior -- are still out of control.

Nevertheless, a sea change is coursing slowly but resolutely through this nation's K-12 education system. I'm writing a series that looks at how schools are moving from a punitive to a compassionate approach to school discipline. The first part was recently published on ACEsTooHigh.com. Here are the high points:

More than 23,000 schools out of 132,000 nationwide have or are discarding a highly punitive approach to school discipline in favor of supportive, compassionate, and solution-oriented methods. Those that take the slow-but-steady road can see a 20 percent to 40 percent drop in suspensions in their first year of transformation. Some -- where the principal, all teachers and staff embrace an immediate overhaul -- experience higher rates, as much as an 85 percent drop in suspensions and a 40 percent drop in expulsions. Bullying, truancy and tardiness are waning. Graduation rates, test scores and grades are trending up.

The formula is simple, really: Instead of waiting for kids to behave badly and then punishing them, schools are creating environments in which kids can succeed. "We have to be much more thoughtful about how we teach our kids to behave, and how our staff behaves in those environments that we create," says Mike Hanson, superintendent of Fresno (CA) Unified School District, which began a district-wide overhaul of all of its 92 schools in 2008.

The secret to success doesn't involve the kids so much as it does the adults: Focus on altering the behavior of teachers and administrators, and, almost like magic, the kids stop fighting and acting out in class. They're more interested in school, they're happier and feel safer.

"We're changing the behavior of the adults on campuses, changing how they respond to poor behavior on kids' part," says Mary Ann Carousso, head of student services for Kings Canyon Unified School District in Central California, which launched a five-year plan in 2010 to revamp the district's 20 schools.

"Suspensions and expulsions don't work," says Javier Martinez, principal of Le Grand High School, Le Grand, CA. His approach is: "How do I help student overcome a problem so that it doesn't happen again?"

"You can't punish a behavior out of a kid," says Jen Caldwell, a social worker at El Dorado Elementary School in San Francisco, CA. "The old-school model of discipline comes from people who think kids intentionally behave badly."

All the methods focus on the social and emotional lives of children, such as teaching children respect, empathy and coping skills. Equipped with their own conflict resolution skills, teachers can defuse most situations in their classrooms instead of sending disruptive kids to the principal's office.

The methods have names such as PBIS (Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports), Safe & Civil Schools, CBITS (Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools), restorative justice, trauma-sensitive schools, and HEARTS (Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools).

PBIS is now in more than 18,000 schools nationwide. Safe & Civil Schools is in 5,000 schools across the U.S. All Los Angeles public schools with social workers use CBITS, San Francisco Unified School District has collaborated with HEARTS to train all of their schools' mental health coordinators in trauma-sensitive practices. Hundreds of schools across the country use restorative justice practices.

In schools that use these programs, words like "de-escalate", "solidify a relationship", "develop trust" and "teachable moments" slide off the tongues of teachers and administrators as they help students recognize, understand and regulate their behavior, as well as ask for help.

PBIS, Safe & Civil Schools, restorative justice, CBITS, HEARTS.....they're not just good ideas. According to some of the research from a second study, Closing the School Discipline Gap, that was released yesterday by The Civil Rights Project, they're absolutely essential if educators want to create a school system where all children can feel safe enough to learn and succeed academically.

But a significant research project at a school system in Spokane, WA, shows that by themselves, those programs may not be enough.

Dr. Chris Blodgett, who directs Washington State University's Area Health Education Center, examined how childhood adversity affects children's academic performance and health in school.

After reviewing the records of 2,101 randomly selected elementary schoolchildren, he found that, even at their young age, 45 percent of the students had experienced one or more of ten severe and chronic types of adversity; 12 percent had three or more.

Blodgett used the CDC's groundbreaking Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) as a model. In that study, the ten types of childhood adversity are:

- physical, sexual, verbal abuse

- physical and emotional neglect

- a parent who's an alcoholic (or addicted to other drugs) or diagnosed with a mental illness

- witnessing a mother who experiences abuse

- losing a parent to abandonment or divorce

- a family member in jail

However, since abuse or neglect can't be identified from school records, Blodgett replaced the five types of abuse and neglect with one -- any type of involvement with child protective services -- and added four other types of adversity. The list of 10 childhood adverse experiences then became:

- CPS referral or placement

- homeless or moving frequently

- parents' divorce or separation

- death of a primary caregiver

- a family member in jail, with a physical disability, mental illness or substance abuse

- witnessing domestic violence, or violence in their neighborhood

Compared with children with no adverse childhood experiences, kids with three or more ACEs were:

- 3 times more likely to fail

- 5 times more likely to have severe attendance problems

- 6 times more likely to have severe behavior problems

- 4 times more likely to have self-reports of poor health

The main take-aways are, says Blodgett:

- Childhood adversity is "pervasive at very high levels almost everywhere we look," even in public schools attended by middle-class kids.

- Because so many children with adversities attend schools, schools themselves are affected. Schools may even be one of the major contributors to childhood trauma, especially if they create environments where fighting, bullying and suspensions are common.

So, exactly what does this mean? The entire educational system needs to change, so that it:

- stops traumatizing already traumatized children;

- reaches out not only to traumatized students who express their trauma by acting out, but also to those who withdraw;

- and creates safe environments where all traumatized children can begin healing.

"We've hit the tipping point and crossed over," says Natalie Turner, assistant director of Washington State University's Area Health Education Center. "In study after study after study, we know that ACEs are pervasive and the issue of adversity is epidemic. We're at the point in taking what we already know and have replicated, and are now saying: 'How do we get systematic change to impact these children in a different way?'"

"Systematic change" means more than schools alone. Blodgett and Turner believe that understanding the effects of adversity and implementing resilience and prevention need to be integrated into all systems -- schools, clinics, youth clubs, hospitals, physicians, families, communities, etc. -- that touch children and families.

Brockton Public Schools in Massachusetts has taken this holistic approach. In 2007, the district sponsored a community-wide meeting. Each of the district's 23 schools sent a four-member team. Representatives from the district attorney's office showed up. So did local police, as well as the departments of children and families, youth services, mental health and local counseling agencies. They spent a whole day working with experts from Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI) at Harvard Law School and Massachusetts Advocates for Children to talk about adverse childhood experiences and learning.

Now all of the district's 23 schools are developing trauma-informed plans, and some have begun integrating them with programs such as PBIS and Collaborative Problem Solving. Some schools saw a 40 percent drop in suspensions in the first year.

The community is also involved. For example, local police alert school personnel when officers visit or make an arrest at an address. Counselors identify children who live at that address so that, "at the very least, the school is aware that a second or third-grader is carrying something around that is a big deal," says Sal Terrasi, director of pupil personnel services for the Brockton Public Schools.

But the very first step in changing a school, a school district and a state educational system is changing the belief system of every teacher and administrator.

"Belief systems are the key, how people think about kids, " says Principal Ed Gomes, who began instituting a school-wide change three years ago at Yosemite Middle School in Fresno, CA. "During the first year, it was very difficult. Some teachers told me that this is not going to work with these kids. They told me that these kids need massive discipline. Even when suspensions and expulsions dropped, the numbers themselves wouldn't convince them." Some teachers left.

"The kids are very easy," says Gomes. "The adults are a different story."

Jane Ellen Stevens is writing a book about how schools, hospitals, homeless shelters, businesses and communities are implementing practices based on ACE- and trauma-informed concepts. The school discipline series is underwritten by The California Endowment.