In Montreal 36 years ago, an 18-year-old from Far Rockaway, N.Y. stood with 11 teammates on a podium. Newly adorned in silver medals, they were among the first female basketball players to be honored by having their nation's flag raised above them to the rafters of an Olympic stadium.

"I got goosebumps," recalls Nancy Lieberman, who after the Olympics went on to have what is widely acknowledged as one of the most successful careers in women's basketball history. She is to date the youngest person, male or female, to win an Olympic medal in basketball. But on that day in July 1976, she says she wasn't simply thinking about herself. "You tried out for you, but you played for your country," she notes.

The 1976 Montreal Games were the first to include women's basketball, the culmination of decades of advancement in female athletics on one of the sporting world's biggest stages. It was also a harbinger of the progress to come in international women's sports. In the years since, the Olympics have voted to include events such as women's soccer, women's ice hockey, and, most recently, women's boxing.

With the historic inclusion of women’s boxing, the 2012 London Games will be the first Olympics in which every sport is open to female competitors. The only sports that remain non-inclusive are closed to men: rhythmic gymnastics and synchronized swimming.

“I’m thrilled now to see some of these young women that have benefited from the work through the last forty, fifty years of women who just wouldn’t go away,” says Lin Dunn, who has coached basketball at the collegiate, professional, and Olympic levels despite never being allowed to step foot on a court as a player herself. “We’re seeing the benefits of that struggle now, and in turn, we’re getting these enormously elite athletes.”

This year’s Olympics will also see the nations of Qatar and Brunei sending female athletes to the Olympics for the first time. After months of back-and-forth speculation, Saudi Arabia ultimately announced that it would send a woman to the London Games despite the fact that no female athletes managed to qualify in Olympic trials. 2012 thus marks the first year in which every participating nation is represented by at least one woman.

Yet, despite extremely diverse backgrounds and circumstances, the hurdles all female athletes have had to overcome to reach the 2012 Olympics are similar to those that their predecessors encountered, mirroring the challenges women faced in basketball in the ‘70s and, to a large degree, still face in many of the events.

Questions surrounding the definition of “womanhood,” the aesthetic beauty of female athletes, and the way in which they are marketed differently than men still arise, even at the highest level of competition. Often, the differences between the way men and women are appraised as athletes comes down to something as simple as their uniforms. After the the Australian women’s basketball team popularized a skin-tight, one-piece Spandex uniform in 1995, other European teams attempted to follow suit over the years in order to make their female athletes more appealing to male audiences.

“I think it’s really sexist,” says Asjha Jones, a member of the WNBA’s Connecticut Sun who played in the EuroLeague and will make her Olympic debut in London, of the Spandex uniforms. “I don’t even think it’s about money or drawing more attention, because in Europe they already have all this support. There was no need to try to force it on people.”

Other female athletes say that they’re often compared side-by-side with men — rather than side-by-side with other women.

“You see us compete against other women, and you see we can be just as physical,” says Swin Cash, who plays for the WNBA’s Chicago Sky and will be competing in her second Olympics this year with Team USA Basketball. “But people always ask me, ‘What would happen if you played LeBron James?’ Why does that matter? Don’t compare me to LeBron James — compare me to Sheryl Swoopes or Lisa Leslie.”

Comparisons aside, the crop of women entering the 2012 Olympics recognize that they are an unusual lot — in number, in opportunity, and in terms of what they have inherited.

“I’ve been fortunate,” Jones says. “I grew up during a time where I knew no better. I didn’t have to go through the struggles that women had to go through in the past. This wasn’t always given to us; we weren’t equal.”

WE HAVE TO FIGHT HARDER

This year, the London Games will host female boxers from 23 countries spanning six continents, including three from the United States. The women’s field is significantly smaller than the men’s and the International Amateur Boxing Association (AIBA) has come under fire for encouraging female boxers to wear skirts in the ring. Though it stopped short of requiring skirts as uniforms, the organization updated its rules in March to allow “either shorts or the option of a skirt.” The AIBA says the purpose of the new clothing policy is to distinguish between male and female competitors, who might otherwise be indistinguishable due to protective headgear.

Despite these flare-ups, many athletes say they are simply looking forward to taking advantage of the international stage that the Olympics provides and showing the world what they can do in the ring.

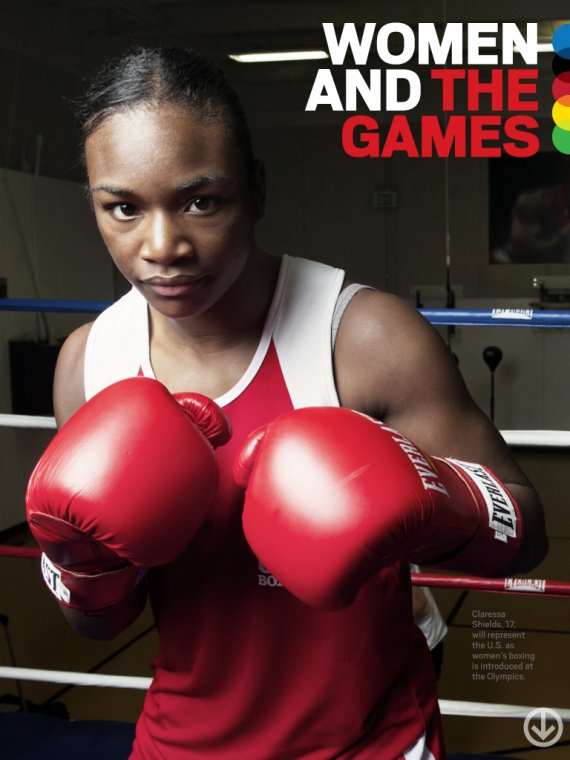

“Since it’s only three of us, we really have to go out and represent,” says Claressa Shields, one of the three female members of Team USA. “Because we’re girls, we know that we have to fight harder. You’re going to see the best in women’s boxing at the Olympics. People are going to say, ‘Wow, I didn’t know a female could box like that.’”For Shields, 17, boxing in the Olympics isn’t just about personal glory and success — it’s also about continuing the dreams of her father. A former underground boxer, Bo Shields landed in prison when his daughter was just two years old. She was nine when he was released.

“He had been in and out of prison for a long time,” Shields says. “He said he wasted his life and he wasn’t able to live up to his potential. His passion was boxing.”

Shields made it her mission to carry out her father’s dream. She started boxing when she was 11, competing in her first fight at the age of 12. Four years later in the fall of 2011, she won the middleweight title in her first open-division tournament, qualifying her for the Olympic trials. She earned her Olympic berth at the world championship in May, suffering her only defeat of the season and bringing her record to 26-1.

Women’s boxing, which had been shut down for most of the 20th century due to the violence of the sport, was revived by the Swedish Amateur Boxing Association in 1988. In 1993, USA boxing lifted its ban on amateur women after federal courts ruled that it constituted gender discrimination. The AIBA added women’s boxing to its world championship in 2001, while the Pan American Games included the sport in 2011.

“Women’s boxing has been gripped by a huge wave of popularity in recent years, accentuating the great commitment, expertise and passion demonstrated by female boxers around the world,” wrote Dr. Ching-Kuo Wu, president of the AIBA, in the organization’s proposal to the International Olympic Committee for Olympic inclusion. “It is the aim of AIBA to see these athletes rewarded with the opportunity to demonstrate their class and skill by competing at the highest level — the Olympic Games. It is the pinnacle in sport and women’s boxing deserves nothing less.”

Women’s boxers are well aware of the stigma that accompanies participating in an aggressive, traditionally masculine event. Perhaps more than any other Olympic sport, boxing is controversial for its operatic violence and the lingering health consequences that arise from being punched routinely and regularly. Critics have focused on the sport’s savagery, though some observers say that allowing women to box may raise the sport’s international reputation (while still exposing the athletes themselves to beatings).

“If women come in, people will feel the sport is more common, not so dangerous, and that would be a very good thing for the image of boxing,” Bettan Andersson, vice-chairperson of the AIBA’s women’s commission, said in 2008, a year before the IOC voted to include women’s boxing in the London Games.

Beyond the sport’s violence and debates about its suitability for women, critics also contended that women’s boxing simply wasn’t competitive internationally. For her part, however, Shields believes that denying female boxers access to the Olympics condemned the sport to mediocrity because it discouraged stronger competition. The best cure, she says, was for the IOC to open the door to athletes like her.

“For them to not even put us in the Olympics and have us fight in junior women’s tournaments, they were keeping us isolated from each other, so they were slowing down our progress,” she says. “Now, girls go to nationals. As we get more matches, more women are coming to the sport.”

Shields is hoping that the media exposure that comes with an event like the Olympics will help elevate women’s boxing in the eyes of the public.

“People are on the outside looking in when they need to get in the action and try to see what’s going on. Then they’ll see that women’s boxing is an elite sport,” she says. “At the Olympics, they’re going to see the best in women’s boxing. That’s what I think is going to change people’s minds. ”

STEPS OF THE DEVIL

Whatever Olympic strides women in Europe and North America have made, many of their counterparts elsewhere in the world are stuck in a time warp marked by limited choices and little support. Among all the countries that participate in the Games, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Brunei are the only ones that have yet to send a female athlete to the Olympics. Qatar and Brunei have pledged to rectify that this year, while Saudi Arabia remained a question mark until recently.

Qatar will send shooter Bahiya al-Hamad, swimmer Nada Arkaji, and sprinter Noor al-Malki. The decision comes amid pressure by the IOC for Qatar to send women, as well as the country’s own domestic push to make sports a hallmark of its international appeal. Qatar has already won the right to host the World Cup in 2022, and is in the midst of campaigning for an Olympic bid in 2020.

The country has worked to heighten women’s sports since the establishment of the Qatar Women’s Sports Committee in 2001. Since that year, Qatari women have competed in international tournaments on national teams including basketball, soccer, and volleyball.

Brunei will send Maziah Mahusin, a 400-meter hurdler who was granted one of the universality spots that the IOC issues in order to maintain equal opportunity and participation. Both countries have repeatedly asserted that their failure to send female athletes to the Olympics before was due to a dearth of talent and not discrimination.

The situation in Saudi Arabia is more complicated. In May, a local newspaper quoted Saudi Arabian Olympic Committee President Prince Nawaf bin Faisal as stating that he did “not approve of Saudi female participation in the Olympics at the moment.” On June 24, the Saudi Embassy in London announced that women who qualified would in fact be allowed to compete. But less than 24 hours after the BBC reported the inclusion of equestrian Dalma Malhas on the Saudi national team, she was disqualified by the Olympic federation; it was revealed that her horse had been inactive and therefore ineligible for months, leading to accusations of tokenism and public-relations posturing on the part of the Saudi government.

After the SAOC reported that “[no] female team taking part in the three fields” available to athletes had qualified, international media outlets and advocacy groups, including Human Rights Watch, called on the IOC to ban Saudi Arabia for violating the gender equality provision of the Olympic Charter.

The resulting backlash sent the SAOC scrambling to find a replacement for Malhas, a task made all the more difficult by the Saudi government’s active campaign to suppress female athletics. In February, Human Rights Watch published an extensive and highly publicized report on Saudi Arabia’s effective ban on women’s participation in national competitive sports. The ban is part of a broader government policy that limits the mobility of Saudi women, who live under a system of male guardianship and are prohibited from driving.

According to the report, the policy “reflects the predominant conservative view that opening sports to women and girls will lead to immorality: ‘steps of the devil,’ as one prominent religious scholar put it.” Under the policy, there are no physical education programs for girls in state-funded schools. Additionally, in 2009 and 2010, the government actively shut down women’s gyms while refusing to grant licenses to fitness facilities for women.

It was in this climate that the SAOC made what cynical critics describe as a calculated decision to send two female athletes to London in order to distract from the larger, systemic issues surrounding women’s sports in the country. “Allowing women to compete under the Saudi flag in the London Games will set an important precedent,” said Christoph Wilcke, senior Middle East researcher at Human Rights Watch, in a statement following the July 12 announcement. “But without policy changes to allow women and girls to play sports and compete within the kingdom, little can change for millions of women and girls deprived of sporting opportunities.”

Despite the barriers still in place in Saudi Arabia against women’s athletics, the IOC is celebrating the announcement as an achievement in international cooperation.

“This is very positive news and we will be delighted to welcome these two athletes in London in a few weeks time,” said IOC President Jacques Rogge in a statement. “The IOC has been working very closely with the Saudi Arabian Olympic Committee and I am pleased to see that our continued dialogue has come to fruition.”

Still, Sarah Attar — who will be running the 800m for Saudi Arabia — and Wodjan Ali Seraj Abdulrahim Shahrkhani — who will be competing in judo — represent a departure from the past. The women are participating in the Olympics under the IOC’s universality rule, and have the unprecedented opportunity to show their countrymen and the world what Saudi women can do given the chance to compete.

“A big inspiration for participating in the Olympic Games is being one of the first women for Saudi Arabia to be going,” Attar said in a statement released by the IOC. “It’s such a huge honour and I hope that it can really make some big strides for women over there to get more involved in sport.”

PROTECTED SPACE..........

“[T]he ruggedness of male exertion, the basis of athletic education when prudently but resolutely applied, is much to be dreaded when it comes to the female,” Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, told Le Sport Suisse, a Swiss magazine, in 1928. “That ruggedness is achieved physically only when nerves are stretched beyond their normal capacity, and morally only when the most precious feminine characteristics are nullified.”

Alas, de Coubertin was hardly alone. Received wisdom during much of the period after he revived the Games in 1896 held that females were weak and — to take things a step further — in danger of suffering reproductive damage or the loss of sexual control if they competed athletically. As historian Susan K. Cahn notes in her book, Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Women’s Sport, experts warned of the “overzealous girl” who was so incited by competition that she could not stop, and would inevitably succumb to the “pitfall of over-indulgence.”

Cahn notes that while advocates from all sides agreed a century ago that women had the right to participate in sports, they differed on what was suitable. A particular point of contention were the so-called “games of strife” — physical sports such as track and field and basketball.

Until the 1920s, female Olympians were relegated to the “gentler sports” such as tennis, golf, archery, and swimming. While these sports surely required strength, agility, and quickness, the fact that they were elite sports and the context in which they developed made them more suitable for women.

“Country clubs were a sort of protected space for women, the same way that women’s colleges were a place where women’s sports developed,” Cahn says. “They were places where women could play outdoors, but it wasn’t especially public. And it was part of sociability, so it wasn’t seen as any real threat to men’s physical or social dominance.”

In 1922, however, women began to take international competition into their own hands. French organizer Alice Milliat helped sponsor the first Women’s Olympic Games, held in Paris. Although the Americans were outmatched by their more experienced European counterparts, the Women’s Olympics were a huge success and male athletic officials took notice. In 1923, the all-male IOC first considered women’s track and field for Olympic inclusion, electing to add five events to the 1928 Games.

The IOC’s grudging support offered an international platform for a new kind of woman athlete, one who could excel at sports previously construed as unladylike. At the same time, women were also getting more enfranchised politically. In 1924, Glenna Collett, an American golfer, told the magazine Women’s Home Companion that “American women, in the first quarter of the twentieth century, have won two rights; the right of exercising the suffrage and the right of participation in sport.”

Such triumphs were short-lived. In the build-up to the 1928 Amsterdam Games, the press had already begun to speculate that the IOC had gone too far in including long-distance women’s events like the 800-meter race. After the race was complete, six of the nine female runners fell to the ground exhausted — a spectacle that the media jumped on and which critics used to justify their resistance to women’s participation in athletic events.

In due course, IOC officials banned women from competing in middle- and long-distance events in the Olympics for more than 30 years.

In a 1929 article opposing female track and field competitors, Frederick Rand Rogers, an educator and pioneer in physical fitness testing, wrote that the Olympics “are essentially masculine in nature” and would cause women to sacrifice their “health, physical beauty, and social attractiveness.”

Nowhere was this fear more evident than in the resistance to women’s basketball. To spare women the stress, public educators mandated that women play a half-court game with teams of six rather than five. As Cahn notes in her book, the new model of women’s basketball reflected “an ongoing effort among educators and popular promoters to make ‘masculine’ sport compatible with womanhood.”

It wasn’t until the women’s movement of the 1960s that the charge of the “mannish” female athlete would come under fire. In that climate, activists took to the national stage to fight for gender equality. Congress passed the Educational Act of 1972, which included a provision addressing gender discrimination: Title IX, which became a primary catalyst for greater participation in women’s sports despite the fact that it doesn’t explicitly address athletics.

“What happened when it passed, those of us in the athletic field, we embraced it and used it as a way to open the doors to opportunities in sports,” says Dunn, who is now the head coach of the WNBA’s Indiana Fever and once served in the Olympics as an assistant basketball coach. “The last 40 years, Title IX has really been associated with sports. That really wasn’t the initial intent.”

Title IX was hotly debated for the next several years by school administrators who didn’t want to spend the resources to implement women’s sports at the same rate as men’s. It wouldn’t be fully implemented until after 1976 — the first year that women’s basketball became an Olympic sport.

Nancy Lieberman had just turned 18 in July that year. She remembers sitting in the locker room before the silver medal game with fellow future Hall-of-Fame players like Pat Summit, Ann Meyers, and Lusia Harris, as well as head coach Billie Moore.

“Billie says, ‘Ladies, tonight is more than just a game,’” Lieberman remembers. “‘When you win that silver medal tonight and stand on that podium, you will change women’s basketball and the perception of women’s sports for the next 25 years.’ And she was absolutely right.”

In the years since, the Olympics have expanded to include events such as women’s soccer, women’s ice hockey, women’s weightlifting, and, of course, women’s boxing.

BE EVER VIGILANT

Decades later, that shift in perception can be seen in the rise of today’s female athletes and the support structures — both institutional and familial — that have contributed to their success.

Team USA Basketball members Swin Cash, Sylvia Fowles, and Asjha Jones each point to the support of their families as pivotal reasons they pursued sports careers, also noting that basketball kept them off the streets and led them to the college classroom.

When Jones was 10 years old, her father signed her up for a recreational league on the weekends in her hometown of Piscataway, N.J. She had been playing for years with friends on a casual basis, and her dad — who, in her words, “was more of a brain” than an athlete — recognized that she had a talent for the game.

“I think he just felt that I was going to be good at it,” she says. “I had already loved basketball, and I think it was keeping me active and giving me something healthy to do.”

Fowles and Cash first picked up a basketball around six years old, playing pick-up games with their brothers and male cousins. Fowles credits sibling rivalry with her desire to push herself on the court.

“My brothers did encourage me,” she says. “They were very hard on me. Once I started playing organized basketball, it was kind of easy for me.”

While her mother was skeptical about basketball’s potential detriment to her schoolwork, Fowles took care to balance sports with academics. Ultimately, it paid off, earning her a scholarship to the University of Louisiana.

“If it weren’t for basketball, I wouldn’t have been able to go to college,” she says. “Basketball gave me the opportunity to go to a university and also do something that I loved. If it wasn’t for a scholarship, I wouldn’t be the person I am today.”Cash also took advantage of her big family to fine-tune her ball-handling skills. She says that eleven aunts and uncles and 75 first cousins helped instill a competitive spirit in her from an early age.

“I just had a passion, I just love to compete,” Cash says. “I was also really blessed to have my mom, who encouraged me to try all the different sports. I had a pretty great upbringing with regards to sports and being allowed to express myself through those activities.”

Cash’s mom also coached her on neighborhood teams, and encouraged her to get serious about her athletic career when the college letters started flowing in around 8th grade. That’s when Cash — who was also involved in track, baseball, softball, cheerleading, and theatre — decided to focus solely on basketball. Cash also points to the role basketball played in molding her during her formative years.

“I grew up in a tough neighborhood where having the ability to play different sports in school kept me engaged,” she says. “It kept me around other people that were trying to do positive things.”

All of these women say they recognize everything that paved the way for them to participate in the Olympics — crediting both Title IX and the pioneers of women’s basketball who forged their way to the Games in 1976.

“It’s the starting point that has opened up all these other doors,” says Cash. “When you open one door, you walk through, then you open another one. I think it really was the catalyst for changing sports not only in the U.S., but also the world.”

As far as female athletes have come, there is still work to be done.

WNBA coach Lin Dunn, who awarded the first full scholarship to a female athlete at the University of Miami and who later built the women’s basketball program at Purdue, points to lingering disparities between men’s and women’s teams. She cites unequal access to sports equipment and scholarship money at the collegiate level, and subpar salaries and media exposure on the professional level, as signs of how much work is left to be done. That fact was on full display last week as the Japanese soccer team made headlines when the world champion women’s team was relegated to economy class during a 12-hour flight to Paris while the men’s team sat in business.

“Be ever vigilant,” Dunn says. “Just because you get a bite, doesn’t mean you don’t want the whole piece. It’s a constant push to keep demanding more to say what’s fair and equitable. Over a period of time, people learn to accept changes and be a little more open-minded, and I’ve seen that over the last 40 years. It just takes time, and I think we’ll continue to see progress in all of these areas. You haven’t actually seen the best of the best yet.”

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store. This story appears in Issue 7, available Friday, July 27.