Update Posted Below

Of the 500 films archived in the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress, less than two dozen were directed by women. As I bemoaned this shameful statistic to everyone within earshot, my colleagues reminded me that very few women have ever written or directed a major Hollywood movie. They're right, of course.

The situation for women who want to make movies is grim. Despite the fact that film schools graduate as many women as men, just 4% of Hollywood directors are women. That's roughly the same minuscule percentage of women archived in the National Film Registry. (You can help change that by voting below.)

The movie business "is absolutely consistently more difficult for women from beginning to the end," said Debra Zimmerman, executive director of the nonprofit organization Women Make Movies.

How difficult? Did you know that a woman has never won the Oscar for best directing? Maybe more to the point, only three have ever been nominated: Lena Wertmuller for 1975's Seven Beauties, Jane Campion for 1993's The Piano, and Sofia Coppola for 2003's Lost in Translation.

"It always comes back to male being treated as the default state of humanity, and female a deviation therefrom. This creates a culture in which men's stories are considered human stories to which everyone is expected to relate, while women's stories are considered an inferior subset," said cultural anthropologist Melissa McEwan, who writes about the political marginalization of gender-based groups on the Web site Shakesville.

When a woman's story is dismissed as "less than," it makes women "others" and makes them seem mysterious to men, explained McEwan. "This underwrites the justification for ignoring women's stories on the ground they are inaccessible and uninteresting to men."

The majority of women directors today are indie, arthouse, or experimental filmmakers -- a creative bunch, however, the statistic also suggests women are being denied access to financial backing. Filmmaker Cristina Cassidy told The Huffington Post, "I honestly believe my current film would have gotten backing in a snap if I was a guy. I know that sounds like sour grapes, but it's true."

Even Nora Ephron, the writer-director (and fellow HuffPost blogger) whose hit movies include Sleepless in Seattle and You've Got Mail, has difficulty getting studios to greenlight her screenplays. "I always think every movie should begin with a logo that says, for example, Warner Bros. did everything in its power to keep from making this movie," scoffed Ephron.

It's a self-reinforcing cycle that results in women-centered films being branded genre films, McEwan told The Huffington Post. "Nora Ephron makes 'chick flicks,' but Michael Bay doesn't make 'dick flicks,' he just makes movies."

Hollywood is still an old boys' club. But does the National Film Registry have to be? Maybe not, because you can nominate films for inclusion. The Washington D.C. chapter of Women In Film & Video (disclosure: I am a member) has nominated the following women-made films to the Registry in 2009:

-- The Big House (1930), written by Frances Marion

-- New Sensations in Sound (1949), animated and produced by Mary Ellen Bute

-- Growing Up Female (1971), written and directed by Julia Reichert and Jim Klein

-- Will (1981), produced by Jessie Maple

-- Big (1988), directed by Penny Marshall

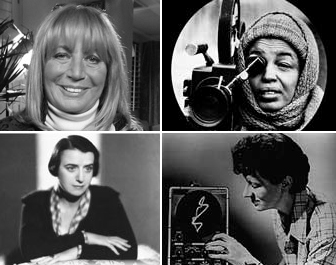

Clockwise from upper left: Penny Marshall, Jessie Maple, Mary Ellen Bute, Frances Marion

(Not pictured: Julia Reichert)

Why these women?

Frances Marion was the first woman to win the Oscar for an original screenplay, and is still the only screenwriter (male or female) to win back-to-back Oscars in this category. She is often cited as the most renowned female screenwriter of the 20th century.

Mary Ellen Bute was a pioneer in the use of abstract animation to "show" sound. Her short film New Sensations in Sound predates Disney's Fantasia, yet it is rarely seen today.

Julia Reichert's Growing Up Female is considered the first film of the modern women's movement. It's a vital resource for young women who have no idea how much has changed for women in just one generation. Since feminist films are not yet represented in the Registry, this movie would be the first one.

Jessie Maple is included in nearly every who's who of film except the Registry. Will is the first post civil rights feature-length film produced by an African-American woman. (Hollywood guilds are more than 80% white.) Maple's film received the Special Merit Award at the Athens International Film Festival.

Penny Marshall is the first woman to direct a film that earned in excess of $100 million at the U.S. box office. The film, Big, also received a nomination for Best Original Screenplay and gave Tom Hanks his first Oscar nomination. Marshall's long career as a producer, director, and actress deserves recognition by the Registry.

Vote today to include more women in the National Film Registry

The Registry has been charged with illustrating the vibrant diversity of American filmmaking, but how can they possibly achieve this goal if the stories they archive are almost exclusively told from a man's point of view?

To nominate the work of Frances Marion, Mary Ellen Bute, Julia Reichert, Jessie Maple, and Penny Marshall to the National Film Registry, click here through November 20, 2009.

Please do vote. (You, too, fellas!) The number of public votes a film receives is a factor seriously weighed during the selection process by the Librarian of Congress and members of the National Film Preservation Board.

Hollywood billboard courtesy of the Guerrilla Girls in 2006.

UPDATE 1.7.09: Of the 25 new titles (Dec. 2009) selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry, just one full-length feature film was made by a woman. Written, directed, and starring Mabel Normand, the silent picture is called Mabel's Blunder. In addition, four short works made by women were added to the Registry: Janie Geiser's 1994 experimental film The Red Book, Helen Hill's 1995 animated short Scratch and Crow, Sally Cruikshank's cartoon Quasi at the Quackadero, and photographer Miriam Bennett's 1932 short A Study in Reds, which spoofs women's clubs and the "Red menace" anxiety of the time.