An industry that’s one of the largest employers of women and one of the fastest job creators in the country also has a huge pay gap.

The average female retail salesperson makes $10.58 per hour, while her average male colleague makes $14.62, according to a new study from Demos, a think tank focused on income inequality. The study found that the pay gap in the retail sector -- a broad category that includes cashiers, salespeople, people stocking shelves and others -- is costing women who work in the industry about $40.8 billion per year.

Put another way: Women in sales and related jobs have work 103 extra days every year just to earn the same amount of money as their male colleagues bring in. That's nearly double the average gap for all jobs, which comes out to about 59 more days per year that women need to work to earn the same as men.

“It’s really striking, because it’s the most common occupation in the country right now,” Amy Traub, a senior policy analyst at Demos and the author of the study, said of retail work. “It’s not a job that’s going away.”

While much of the public discussion about pay inequity and the role of women in the workplace has focused on how best to get professional women into visible leadership positions, the average woman is more likely to be toiling away in one of the low-paying roles highlighted by the study than worrying about how she'll move into the C-suite, Traub noted. Women held many of the middle-class government jobs that disappeared during the recession and recovery. As these positions disappeared, more jobs sprung up in low-wage sectors like retail and fast food.

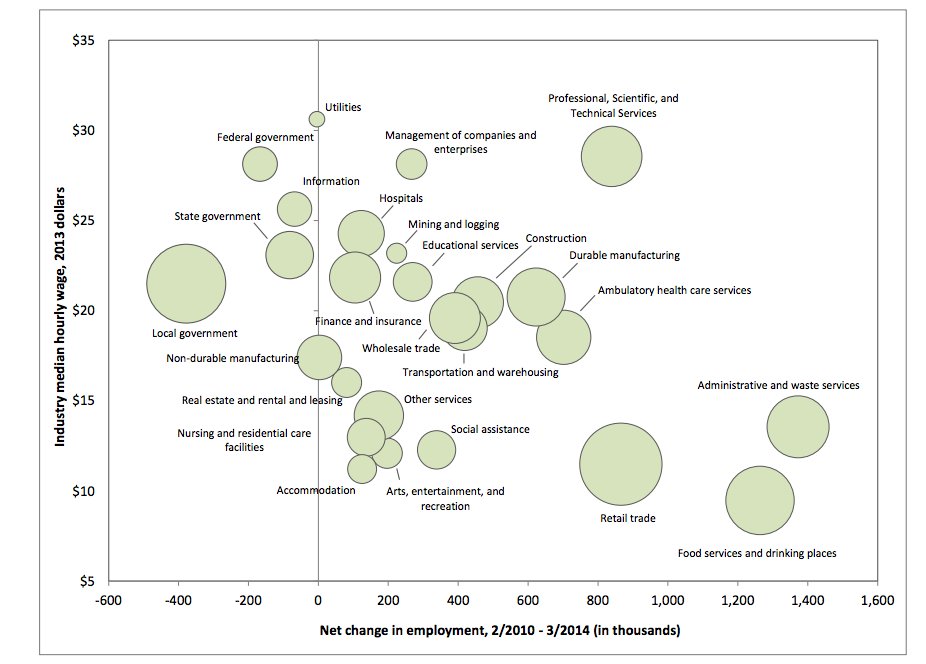

The chart below from the National Employment Law Project shows which sectors have grown and which sectors have shrunk during the recovery.

One reason for the pay inequity in retail could be that men and women keep getting slotted into the sorts of jobs that keep the gap wide. Ariane Hegewisch, the study director at the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, noted that occupational segregation, or "men doing ‘men’s jobs’ and women doing ‘women’s jobs,’” has been stuck at a high level for the past 15 or so years.

For example, Hegewisch noted that men often end up selling higher-priced items, like cars, earning them higher commissions. Men are also more likely to work in high-profile, expensive retailers, while women are more likely to work in smaller shops with less traffic.

“If you sell a TV, you have a much larger commission than if you sell a T-shirt,” Hegewisch, who did not have any part in the Demos study, said. “It’s not just exactly the job you do, but really what your opportunity is to sell.”

Out-and-out discrimination also likely plays a role. There’s a history of female workers suing Walmart and other retailers, claiming they were paid less than men in similar jobs and denied access to promotions and higher paying roles. (The Supreme Court threw out the Walmart case, ruling the workers couldn’t qualify as a class).

In another, more recent suit against Sterling Jewelers -- the parent company of Jared and Kay Jewelers -- female workers alleged they were paid significantly less than their male colleagues despite having more experience.

More than 1 million women working in retail live in or on the edge of poverty, the Demos study found. That’s because more than half of female year-round employees working at large retailers earn $12.25 an hour or less. For a woman working 40 hours a week, that wage amounts to about $25,000 a year. And as the study points out, having a regular schedule of 40 hours a week is rare for many employees in industries like retail or fast food.

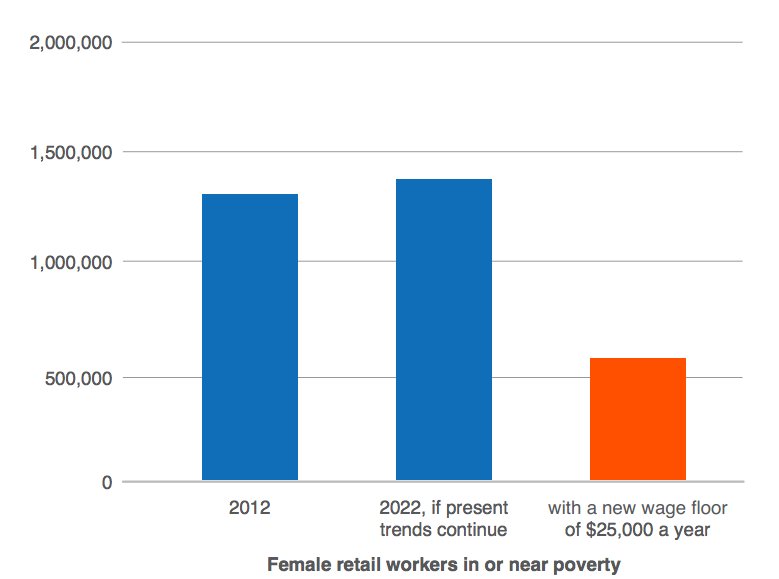

The chart below from Demos shows how many fewer female retail workers would have been living in poverty in 2012 if the industry paid at least $25,000 a year.

One in five of those women working at large retailers and making $12.25 or less is her family’s sole bread winner, the study found.

Lashanda Myrick is one of those workers. Myrick, 37, said that after spending $550 a month on rent, another $200 or so on food and even factoring in some public assistance, the $10.20 an hour she earns working at Walmart isn't enough to support her two kids.

"I cant even tell you the last time that I bought my daughter an outfit; I can't even tell you the last time that I bought myself an outfit," said Myrick, who lives in Denver, Colorado. "It's crazy, especially when your kids are into the fashion and you cant get them what they want. It kind of breaks my heart."

Myrick, who relies on her family to take care of her 12-year-old daughter when she works the overnight shift at Walmart, said she constantly has to choose between buying items for her kids and making sure there's food on the table. Right now, she's helping her son look for a way to afford the college he plans to attend in the fall.

"We are stuck on what to do, trying to get grants and loans and stuff," said Myrick, who plans to take part in protests at Walmart's shareholder meeting later this week. "I want my son to go to college, and I want him to be whatever his heart desires. By me not having the money to do it, I'm in a bind."

Kory Lundberg, a Walmart spokesman, said that Myrick is "a great example of opportunity Walmart provides associates," given that in less than a year she advanced from a temporary associate working for a bit more than $8 an hour to a full-time staffer earning more than $10 an hour.

Lundberg also described as "pretty typical" the experience of Noemi Flores, an assistant manager at a Walmart store in Pearsall, Texas. In an interview arranged by Walmart, Flores said she has worked for the company for 28 years. When she first started as a cashier at slightly above minimum wage in the 1980s, Flores said, she relied on public assistance to help her afford basic necessities for herself and her three children.

But throughout her time at Walmart, Flores said, she has moved up the ranks and the pay scale, helping her get off public assistance and even buy a home. Flores, who now makes $35,000 a year, added that Walmart paid for her to get her GED.

"Walmart is there for you," Flores said. "If you're not taking advantage of it, who's fault is that?"

For the more than 1 million women working in retail who live in or near poverty, the Demos study lists several possible solutions. One is to raise wages for everyone. Because women are more likely to be clustered in low-wage positions -- women make up two-thirds of minimum-wage workers -- raising the base wage for all retail workers would disproportionately help women, Traub said, with only a small cost to companies and customers.

If the retail industry raised its wage floor to $25,000 a year for full-time workers, it would cost about $21.5 billion, the study found. That’s less than 1 percent of the retail industry’s total annual sales, or just 4.1 percent of the retail industry’s payroll expenses in 2012, according to the study.

The study also suggests making it easier for workers to have a regular schedule. New York and some other states already have laws on the books requiring that businesses must commit to paying for at least four hours of work in order to schedule an employee for a shift. But Traub said the problem is that those policies aren’t national, and even where they exist many workers simply don’t know their rights.

“The idea is you don’t arrange child care, arrange transportation, get into work and get sent home immediately without being paid,” Traub said. “The problems of scheduling are very real, and even if you’re making a good wage, if you’re not getting scheduled for very many hours, that’s going to fall short, and you’re still not going to have enough money to make ends meet.”