English writer John Berger famously summed up the roles of men and women in media in his 1972 book Ways of Seeing, stating, "Men act and women appear." Over 40 years later, a new study suggests that this disparity still holds true.

Published in Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, the study looked at 1,055 television commercials, giving researchers a general idea of how often women's voices, versus men's, were used in either voiceover or spokesperson roles.

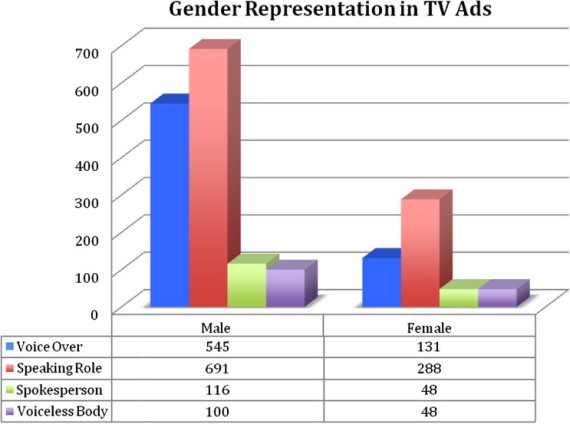

The results were far from balanced: Male voices were used in voiceovers 80 percent of the time. And while still outnumbered, female voices only became more represented when they were also on-camera and their faces or bodies were shown.

"There's probably something about the representation of women's bodies which -- and there's no good language to use on this -- allows them to speak, if you will," Mark Pedelty, Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Minnesota and co-author of the study, told The Huffington Post. "Of course we found that very problematic."

Pedelty and his co-author Morgan Kuecker performed a content analysis on 1,055 recent ads culled from YouTube and found that male voiceovers outnumber female voiceovers 4:1, which reflected past research on the topic. In 1975, men dominated 91 percent of voiceovers, but that number dropped to 80 percent by 1998, illustrating only a minor step toward gender parity over the course of nearly 25 years.

Graph courtesy of Morgan Kuecker

What Pedelty and Kuecker added to the literature, however, was that a woman's odds of being heard double when her image is also depicted ("Speaking Role" and "Spokesperson" in the chart above). This phenomenon -- that the likelihood of a woman's voice being heard is significantly increased by her visual presence -- is what the researchers called "scopocentric sexism."

"There's still this sense that the voiceover, the disembodied voice, is one of reason and objectivity. Because of sexism in our society, that is still seen as a masculine domain," Pedelty said. "I wouldn't want to overstate it, but in some ways it's like the voice of God. I think that that inculcates a sexist expectation of who speaks and who gets to speak authoritatively."

So, how did voiceless women become the norm?

Perhaps the most comprehensive look at sexism in advertising is Jean Kilbourne's "Killing Us Softly" documentary film series, the first of which came out in 1979 and the fourth and most recent in 2010.

Kilbourne began looking into ads in 1968, after a brief stint in modeling proved "soul-destroying," she told The Huffington Post. The objectification and sexual harassment she experienced led her to explore the relationship between image and power in the media.

"I started collecting the ads and looking at them, and I gradually saw a pattern in them," Kilbourne said.

Kilbourne's periodic, in-depth research confirms Pedelty's observation that not much has changed over the last 40 years when it comes to the advertising industry's depiction of women. As she's noted in her films, the female body is often broken up or used to illustrate the product itself in ads, both of which cause women to be seen as objects, not people. A lack of voice only further dehumanizes women, as visual and auditory cues often go hand in hand.

Jean Kilbourne speaking at Hunter College's SPARK Summit in 2010

Only allowing a woman to speak when she's seen reaffirms that her currency is not her mind but her body, Pedelty explained. But the fact that men's voices are so overwhelmingly used in lieu of women's may result from a subconscious bias.

"There's what you might call a tautology there -- people expect the voice to be that of a man," said Pedelty, noting that the research confirming male dominance in voiceovers isn't always reflective of a preference per se, but rather an assumption. A 1995 study showed that even when a woman's voice was used on television, many children later remembered it as that of a male's.

While there is research that has shown a slight preference for male voices in ads, this bias could also be chalked up to that aforementioned tautology. If masculine voices are the norm, wouldn't people simply be more accustomed to hearing them and therefore prefer them?

"In most of these studies, you find that there is not a major difference [in preference]," Pedelty added. "But even a marginal difference can sometimes make an advertiser point to that and say, 'Well, we're going to bow to expectations.' It's essentially giving the people what they want."

Yes, we're hearing more women in ads, but the progress has been minimal.

Despite the slight improvement in voiceovers, Pedelty said that this segment of media is a particularly "tough category to crack for women." And Kilbourne doesn't seem to think that the media landscape has improved at all, even with the 11 percent increase in female voiceovers.

"In some ways it's worse [today]," Kilbourne said about the objectification of women in advertisements. "There's more pressure than ever on women to look a certain way. These days, that starts very, very young."

She explained that the progress has been mostly in awareness of these issues and how they're problematic. But this is only a small stride in the big picture of equality in ads, and not too many people seem to be talking about voice inequality just yet.

Apple ad from the study featuring traditional gender roles and a male voiceover

The male voice has become the default, the universal, the given. Or, as Kilbourne put it, the tendency to hear men over women in ads is an extension of the "male gaze" because "the woman is the object and the man is the subject," much like what Berger observed in 1972.

These new findings on voiceovers show that the media's sexism is so pervasive because it's often subtle or even unintentional.

"The thing that's hard about [voice] is that a lot of that isn't really intended by the advertiser," Kilbourne said. "The subtlety in which a woman's voice is used in conjunction with her body, that's mostly a result of the internalized stuff that's in advertisers in the same way it is the rest of us -- that men are the voices of authority and a woman’s voice has power in so far as it's connected to her actual image."

The only way to overcome this bias is to educate yourself.

Advertisers don't seem to have much incentive to push against the status quo, even if it means making a positive change. Brands like Dove, Always and Verizon have had success going against the grain, but Pedelty and Kilbourne said that it's likely that most advertisers will stick with what works.

Essentially, don't expect a huge voiceover overhaul anytime soon.

Mercedes ad from the study that challenges traditional gender roles

Both Pedelty and Kilbourne agree that the key here is increasing media literacy so that consumers are aware of the problem and are able to identify it. This type of education should start as young as possible, before the silent woman becomes the norm for children. Since parents aren't often media literate themselves, Kilbourne said that it's important for schools to help contextualize what kids are seeing and hearing in ads.

Changing expectations of youth is certainly a step in the right direction, but making people of all ages aware that there's a problem would be an enormous leap towards equality. Women may not be able to directly control whether or not they have a voice in advertisements, but they have the power to speak up about this disparity in the real world.

Take it from Kilbourne: "Once you become more conscious of these things, they have less power over you."