"I never fell in love, it was just there," Dr. Urmilla Khanna said, as she giggled at the silliness of the question about how she fell in love in an arranged marriage. A question she has fielded with fondness since she moved from India to the United States with her husband Dr. Kris Khanna, whom her parents had arranged for her to marry, over fifty years ago.

A lot of people will ask me, 'If you have an arranged marriage, how did you fall in love?' I never fell in love. It was just there. It didn't take much in the doing to make it happen. Both of us kept sacrificing for each other. In fact, in our latter time in our life, once in a while, I would say to Kris,'I've never understood the definition of love.' And he would think about it and say, 'You know, I think the only definition I can give you is sacrifice.' Unless there is that understanding for each other and that sacrificing for each others needs, how do you make it happen?

She shares these memories with me, after Leeya Mehta graciously introduced us, in a private interview to mark the launch of her new memoir Boundaries of the Wind. A writing process she began to write shortly after her husband died of Parkinson's in 2003 and worked on over the next ten years. The book launched October 17th, 2015. This is her third published work. Her first two short nonfiction pieces were included in the anthology Patchwork: Stories from the Dining Table.

In a few weeks, or maybe a few months, I would leave again to enter the next stage of my life, that of ghar-grahasthi, the stage that encompasses marriage, career, and family. Dreams and visions of my new life were endless--a perfect husband, a small home with café curtains in the kitchen, two little children, and a career in medicine. I was twenty-five, and the year was 1961.

And so begins the tale of a young woman living in between the past and the present of women's rights; two countries in the middle of extreme political, cultural, social, and educational shifts; the loyalties that lead her to comply with tradition; and ultimately the silent and powerful persistence to live her life on her own terms in her own time.

Pita-ji, as she addressed her father, had already broken tradition with pride. He had deliberately educated both of his daughters to the highest degrees possible. Pita-ji even went as far as getting his first daughter to be the first woman to enter an all male engineering college enabling her to become the twelfth female engineer in India. (You will have to read the book to find out how.)

He was equally adamant about the importance of higher education with Urmilla and supported her all through medical school. Pita-ji wanted his daughters to have the skills to be independent, even as his friends reminded him of how old his daughters would be when they graduated, making them less desirable. But marriage, that was another matter. Finding the right match for his daughters' marriage was his destiny to fulfill.

Parents believed that they could not achieve moksha--deliverance of the soul from rebirth and restless transmigration--and would have to live their next life in papum--sin--if they failed to complete ther duties in their present life. Getting us married and settled in our new homes was a prime prerequisite for them to complete their life of ghar-grahasthi and enter the next stage--the life of renunciation--and seek peace and moksha.

I was aware of such views being prevalent in the lay society, Kapildas's society. My father was an educated man, a successful engineer. I began to realize that the barrier that separated Pita-ji's intellectual reasoning from his fear of going against the samaj, the cultural beliefs of the society, was

indeed rigid and immutable.We, his two beloved daughters, were now his burden.

We are allowed to witness the complex arguments that two sisters must make to themselves, each other, and their parents as their modern educated beliefs challenge the traditions of trading women as commodities. The sister's individual decisions provide us with a surprising turn where we get to experience how Urmilla and Pramilla's personal choices are ultimately carried out.

Dr. Khanna describes the web of loyalties and relationships steeped in tradition and spirituality that weave the theme of Karma throughout. This is not the Karma of vengeance in the popular "What comes around goes around" idea, but a more personal belief rooted in her parent's views.

As events unfold, whether they are perceived as positive or negative their unraveling is part of a greater life purpose and there is always good in it. Each time a physical, emotional, or professional period closed another greater one would begin. Instead of grieving there was a sense of embracing the next step, of facing challenges and joys head on without resistance.

Isn't that what my grandmother had always taught me? "Fear not, beta, for fear gets you nowhere. When fear grips, bank on your karma." So I did. I trusted my karma.

Beautiful imagery and detail allows the reader to capture firsthand what it was like for an Indian woman to mix in the circles of academia in Connecticut and Michigan at a time when there were few Indian immigrants in the country. We are made aware of Dr. Khanna's American transition with a contrast of the senses: the silence of winter, the abundance of black, browns, and grays, the absence of a wealth of spices and the discovery of "American legs," as she encountered pantyhose for the first time.

Traditional culture clashes like fixed prices, having house hold appliances, and not needing servants lead way to more serious cultural transitions like: American solitary vs. Indian communal child birth experiences; raising monolingual kids from a multilingual culture; finding time to be mom, wife, an immigrant pediatrician in pursuit of an American Pediatric license, even when it meant letting go of her sari and her long hair for a more western look, and leaving her children for long periods of time-- ALL GUILT FREE.

Without being didactic or preachy this personal narrative dives deeply and beautifully into the daily trials of women's work from an American and Indian point of view without judgment to either. The reader is guided through the decisions Dr. Khanna had to make and the doubts she had to ignore from her husband, her peers, and her bosses. Each with their own traditional ideas of what she was capable of, even with one medical degree in hand, in order to gain access to high level career opportunities beyond motherhood at a time when it wasn't common for women to do so.

The stresses and evolution of women's rights, considered the trials of yesterday's modern woman, are still very much present in the lives of women today who continue to juggle the demands of careers, partnerships, and children without equal pay for equal work make Dr. Khanna's memoir relevant now.

Boundaries of the Wind is a wonderful example of a different immigrant narrative, filled with contrast but not necessarily extreme struggle. It is a testament to the power of higher education to provide access to professional opportunities for women in the U.S. and India, even in the face of racism and sexism. It is an inspiring account of a woman determined to live within the contradictions of culture, tradition, history, and family without being weighed down by them but to create for herself the life no one thought she could have.

*All images are courtesy of Dr. Urmilla Khanna.

Listen to her discuss her writer's journey with me.

(Thank you Cesar from Sound Cloud for helping me make the following sound clips a success.)

On writing a memoir, right and left brain writing, and letting go to write with passion:

On the idea of a "mythical America:"

On being loyal to her career dreams as a mom without the guilt:

On her personal take on the Hindu philosophy of Karma:

Dr. Urmilla Khanna & Dr. Kris Khanna on the day of their wedding.*

Dr. Urmilla Khanna & Dr. Kris Khanna on the day of their wedding.*

Dr. Urmilla with her sister Pramilla.

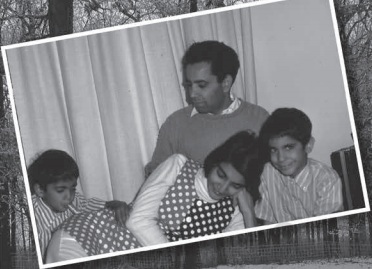

Dr. Urmilla with her sister Pramilla. Family Time

Family Time