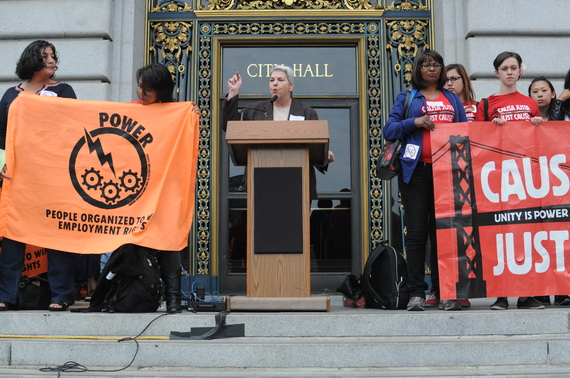

Beverly Upton, head of the SF Domestic Violence Consortium, addressing a large crowd

Beverly Upton, head of the San Francisco Domestic Violence Consortium, addressed a crowd from the steps of City Hall in San Francisco. She was flanked by advocates from queer and transgender groups, but mostly by women's rights groups. The event was "Women Against SCOMM," and they were protesting Secure Communities (SCOMM), a program which allows local police to enforce immigration law typically enforced only by federal officers. Upton spoke of how SCOMM had unique consequences for women and girls, who often refuse to go to the police after instances of domestic violence or sexual assault.

This is only one of several instances where there is a strong overlap between women's rights and immigrant rights, and why advocates in either community cannot address the needs of their community without addressing issues in the other.

SCOMM, a federal program, stands alongside other laws like Arizona's SB 1070 and Alabama's HB 56 in discouraging immigrant communities from going to the police by having local police enforce immigration. This takes a toll on community safety in general as every immigrant without status becomes fearful of the police, however, it is especially felt by the women and girls who are victimized in these communities: they have nowhere to go for help because many fear deportation and separation from their families more than being labeled as an easy target. Because these women cannot report sexual predators, or any criminal for that matter, they remain a threat within the undocumented community as well as the general population.

On the border, the crisis that has been taking place has been heartbreaking. Like in any humanitarian crisis, women pay a higher price: in Honduras, Guatamala and El Salvador, girls that come of age are often visited by gang members and told they will either submit to becoming their property and sex trafficked, or they will be killed. One 14 year old girl who escaped Central America recalled how her friend was gang-raped and dismembered, her body strewn alongside the road to school to send a message to the rest of the girls about refusing the cartel.

Although a better immigration policy would not have prevented the terrible conditions we see in Central America, it could have given them a safe place to run to, instead of having them "warehoused" at the border to be deported by our current broken system.

Jose Diaz Balart recently interviewed a survivor: she had been through the desert and was in tears, clearly still suffering the effects of trauma. She talked about the children who had died along the way, the sex traffickers and murderers she had to get past, and that people had caught and hurt her along the way. Mostly, however, she talked about how her brother had been shot and killed in front of her when he refused to become the property of the gang, how they came for her after she turned 17 and how they would come for her again if she were deported. This is why many of the children making the dangerous trip have been sent for by mothers who feared their children faced a strong chance of dying along the way, but certain death at home.

Today, much of the debate in immigration revolves around how to treat the young boys and girls who would have been trafficked into sex slavery or killed. While some would prefer to imagine this doesn't happen, I personally worked a case involving a sex slave kept by a Kuwaiti diplomat in Manhattan and, if it can happen in New York City in front of a million eyes and lot of police for years, it can happen anywhere.

Finally, in my experience in the undocumented immigrant community, one of the most common stories is of a mother fleeing domestic violence with her children a la 'Not Without My Daughter.' One such example is a cofounder of my organization, Erika Andiola, whose mother fled extreme domestic violence that local police refused to do anything about.

Talking with DREAMers, people who were brought to the country as children by their parents without status or who overstayed a visa, you find many similar stories of mothers escaping fathers in places where domestic violence is overlooked, or even part of cultural norms; I've even heard stories of women trying to escape and being dragged back (often literally) several times until a desert and national borders were placed between them and their abusive husband.

The immigrant narrative in this country is full of tragic stories people have fled, and women who have both survived the unimaginable, and paid a higher toll when immigrants are scapegoated in our country: from the violence against refugee women that is considered acceptable in much of the world, to the crowds who come out to taunt women and children going into a women's shelter away from an abusive spouse they depend on for their immigration status; from the frightened mothers with their children inside a bus in Murietta where "USA!!! USA!!!" is chanted to scare them, to the trauma suffered in silence from those who fear deportation from their families and home more than victimization, to the young girls who escaped sex traffickers and are at the border today hoping that they won't be sent back: the immigrant story has always been difficult for women, and issues involving immigrant women need to be given a special place in advocacy within both the women's rights and immigrant rights movements.

Advertisement