Like a Habsburg eagle the ViennaFair, which ran Oct. 10-13, looks simultaneously towards the capitalist West (half its exhibitors come from Austria, Germany and Switzerland) and the post-Communist East (nearly two-fifths come from Central & Eastern Europe).

The eastern lurch has long been sponsored by Erste Bank, who do business in the region, and was strengthened by the Fair's 2012 acquisition from Reed Exhibitions by two Russians, Sergey Skatershikov and Dmitry Axenov. Skatershikov, an art investment specialist, was perceived as the dominant partner, but shipped on full control to Axenov, a property tycoon, before you could say wienerschnitzel.

Suspicions that the Fair may not be the art world's most bracing investment were compounded by some of this year's innovations, which included ditching the catalogue and shifting the entrance from the swanky glass and marble foyer at the front of the Messe Wien exhibition center to the tacky glass and tarmac doorway round the back.

Once inside, however, the Fair was crackling with energy, underscored by the exotic presence of artists from Albania, Almaty and Azerbaijan, and exhibitions flown in from Prishtina, Kosovo and Tbilisi, Georgia. There were also a lively talks program and bevy of imaginative social events to keep connoisseurs calling (and downing) the shots after dark.

Credit for this cosmopolitan cocktail must go to the Fair's Artistic Directors, Vita Zaman and Christina Steinbrecher, although whether Vitina (as these plutonium blondes are collectively known) should be considered The Stars Of The Show, as implied by their diva-like photo in the front of the fair's VIP Booklet (bizarrely dominated by Sigmund Freud's essay on Happiness), is another matter.

The four-day fair attracted 23,000 visitors. Nearly one-third of those were crammed into what Vitina dubbed a 'grandiose' vernissage -- an adjective which, in the absence of Dom Pérignon, Beluga caviar and breathing space, needs careful handling.

Heroic sprang more readily to mind.

Every art fair worth fretting about needs controversy and the ViennaFair found it in the unlikely shape of neon tubes from Latvia. Andris Breže's "White Square," arguably the most powerful work at the Fair, was destined to headline the stand of Riga's Alma Gallery -- until a Belgian gallery across the aisle objected to its overwhelming presence, and got it shifted to an obscure corner of the VIP Lounge. Heroic and grandiose were not among the words spluttered by gallery owner Astrīda Riņķe to describe a decision that amounted to an anti-Latvian snub -- Breže having been shortlisted for this year's Purvitis Prize, the country's most prestigious art award.

Riņķe founded her gallery in 2005 and has built it up with exquisite taste; the monochrome paintings of Barbara Gaile, which she showed at Art Vilnius in 2011, are the subtlest I have seen at a fair in Central Europe. Following in her regional wake are an emerging generation of young female galéristes whose passion and energy offset the challenge of selling art in countries where few people buy it.

Dora Bulart from Varna (Bulgaria), Olga Temnikova from Tallinn (Estonia) and Katrin & Vesselina Sariev from Plovdiv (Bulgaria) are names that spring to mind, but the career of Romania's Anca Poterasu is particularly improbable. Poterasu hails from a village in rural Maramures near the Ukrainian border, where most houses have pitchforks on the wall rather than paintings. When I first met her -- at an art market symposium in Bucharest in 2007 -- she was the perkiest person in the audience and, fresh from a Master's Degree in European Social Politics at Bucharest University, was adamant that -- armed only 'with my laptop and my scooter' -- she would be an art dealer.

Poterasu (above) opened her "Little Yellow" studio project in 2009, and a permanent space in May 2011; the nascent Anca Poterasu Gallery took part in Art Moskva four months later. This year's ViennaFair represented a new stepping-stone in her irresistible rise, and her innate gift for presentation -- already apparent in 2010, when she contributed to the Heroes Corner section on East European art which I curated at the Budapest Art Fair -- was again in evidence in Vienna.

Another gallery to make its aesthetic mark was Triumph of Moscow. The understated elegance of their booth, in schizophrenic contrast to the cluttered confusion they had offered up at Art Moskva just a fortnight before, bore the unmistakably cool imprint of their International Curator Yana Smurova. It even featured two of Dmitry Gutov's immensely heavy ironwork compositions, which require a degree in engineering to dangle successfully from flimsy partition walls. Whether this tour de force was worth the effort is another matter. The versatile Gutov has been welding these works for years. Time to move on.

The same applies to Oksana Mas, whose painted eggs -- first used in their thousands to portray the Virgin Mary in St Sophia's Cathedral in Kiev in 2010 -- have runnied their course and now scramble her message. Being displayed (by Ukraine gallery Mironova) next to the latest inanity from Ilya Chichkan doesn't help either. Gutov was luckier -- placed by Triumph alongside Pavel Brat's intriguing paper and aluminum roundels resembling slices of andouille, and Maxim Ksuta's line-like photographs evocative of Chinese calligraphy (below left).

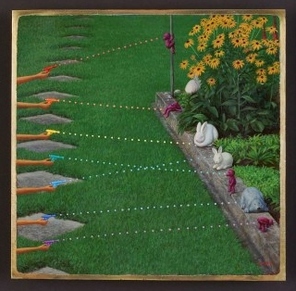

The other outstanding Russian exhibitor was RuArts, where I enjoyed Alexander Zakharov's anarchic garden scenes (above right) and Vita Buivid's subversive floral still lifes. Figurative painting of equal quality could be admired at Budapest's Erika Deak (Attila Szücs) and Sofia's 0-GMS Gallery (Diana Machulina).

The Fair also offered an orgy of Geometric Abstraction, much of it from Warsaw: by Dorota Buczkowska at Starter; Małgorzata Szymankiewicz at BWA; and Mateusz Szczypiński, with his witty psychedelic Crosswords (detail below right), at Lokal 30. Zofia Kulik's black-and-white Patterns, beautifully displayed in the non-commercial section of Art Moskva, were here on sale at Le Guern. These patterns look abstract from afar, but turn out to consist of repeated photographic motifs -- knives, tulips and nudes in the example illustrated below.

There was similarly monochrome appeal to the abstract works at Drdova (Prague) produced by DJ-cum-Artist Daniel Vlček in tribute to his musically abstract compatriot František Kupka. Colorful abstract brushwork could be admired at Temnikova (Merike Estna) and Jecza Gallery of Timişoara (Genti Korini). Sounding a heavyweight, if slightly anachronistic, note in the field was Nadia Brykina, showing powerful mid-century works by Marlen Spindler and Vladimir Andreyenkov. Brykina's erudite approach to post-war Russian art has yielded a string of superb catalogues -- the latest devoted to the highly stylized sculptures of Igor Shelkovsky (on show in her Zurich gallery through December 21).

The Fair's Eastern European section was also strong on conceptual works. Vartai of Vilnius led the way with a magnetic-tape curtain by Žilvinas Kempinas (subject of a startling show this summer at the Tinguely Museum in Basel). Nadine Gandy from Bratislava displayed intriguingly artistic, single-sheet typescripts by Milan Adamčiak, redolent of Soviet samezdat and produced in 1969 after Adamčiak had joined a hunger-strike in memory of fellow-student Jan Palach, who burnt himself to death in the wake of the Prague Spring.

Margit Valko of Kisterem (Budapest), returning to her favourite whites and off-whites after a brief incursion into colour (green and black, anyway) with Tamás Kaszás's chalk drawings at Basel in June, had the longest work in the fair: an astonishing 30-foot scroll by Kamilla Szíj. Her city rival Ani Molnar, with works by Emese Benczur and Szilárd Cseke, struggled to compete in a conceptualist domain that is not her forte. But her current gallery show in Budapest, of witty wood carvings by György Szász and Balázs Csepregi (whose ingenious Kossuth Utca is pictured below), is worth sailing down the Danube to see (through Nov. 29).

Hungary, with seven galleries, figured prominently at the fair, and the country's Viennese profile was elevated still further by an exhibition of Young Hungarian Art from the Erste Bank Collection at the Hungarian Embassy, hosted by Ambassador Balazs Csuday and Attila Ledenyi -- boss of the Budapest Art Market fair that opens on Nov. 27.

Pursuing the East European theme was an exhibition at the Vienna Albertina (through December 1st) devoted to a small part of the Gazprombank Collection, begun in 2011 under the dynamic guidance of Marina Sitnina, and encompassing Russian art since the 1990s. Although this three-room overview was styled Dreaming Russia, the works on display were essentially intellectual. Their visual appeal was brought to the fore by Elsy Lahner's elegant hanging, with its judicious contrast of color and monochrome.

This appeal was firmest in the long, narrow back room, where one wall was lined with Yuri Albert's Self-Portrait with Closed Eyes (1995) -- an array of vari-sized white panels covered in Braille -- and the opposite one with Nikita Alexeyev's 2009 Impressions of Places & Events: a parade of square canvases alternating between abstract paintings and Russian inscriptions.

Hung in isolation, these whopping ensembles -- each comprising over three dozen pieces -- might appear repetitive and self-indulgent. Here they complemented each other exquisitely while channelling attention to the small back wall and its Chuikov No Entry sign, granting it the status of a secular icon: no mean feat for a work, painted in 2005, which looks to western eyes like a tardy re-hash of an idea peddled by French artist Jean-Pierre Raynaud since the 1970s.

Steps led down to a darkened second room, with its Sergey Bratkov Full Moon video-stills, Sergei Ogurtsov book sculptures, and Vadim Zakharov tile patterns evoking characters from Gogol's Dead Souls. The main hall featured seven works, including Arseny Zhilyaev's Peace Our Ideal -- a slogan spelt out in Cyrillic letters formed by angular strips of wood -- and Alexander Djikia's Portrait of Gagarin, drawn with a giant red pencil presented to the ill-fated astronaut as a child.

But here, as elsewhere in Vienna this October, women predominated: Dasha Irincheyeva with her "Empty Knowledge" bookshelf installation; Alexandra Paperno with her artfully faded grisaille floor-plans; and Olga Chernysheva with a series of woolly bob-hats, photographed from behind to semi-abstract purpose and entitled, perhaps meaningfully, "Waiting for the Miracle."

Chernysheva, like many conceptualists, has the knack of coming up with clever ideas, then worrying them to death like a dog with a bone. Here the hall's pillars and gentle arches salvaged rhythm from monotony -- spilling forth a split-frame succession of super-sized Smarties.

Tubular belles: the sound of Vienna this fall.

all photos © Simon Hewitt

.