Politicians, take note: American parents want to work outside the home. A recent Pew report revealed that the portion of mothers in the U.S who are stay-at-home parents rose to 29 percent in 2012, up from 23 percent in 1999. But many of those women aren't staying home because they want to. Among mothers with children under age 18, the portion who would prefer to work full-time increased from 20 percent in 2007 to 32 percent in 2012.

So why aren't more parents working outside the house? Because our society doesn't make it easy. High-paying jobs are hard to come by, as is affordable child care. Parents who do manage to find both work and child care struggle to sustain it: According to a 2013 Pew report, 53 percent of working parents with kids under 18 say it's difficult to balance their professional demands with the demands of family.

There are steps the country can take to help change that though. Here are nine ways U.S. government and business leaders can make it easier for Americans to be both parents and professionals.

1. Pass the Pregnant Worker's Fairness Act.

Heather Myers was working at Walmart when she got pregnant in 2007. At seven months, she told her boss that her doctor said she would need to carry a water bottle with her as she stocked shelves to avoid getting a urinary tract infection. But her boss denied her request twice, forcing Myers to decide between keeping her job or maintaining her health. She left the job. Kimberly Erin Caselman, who worked at a California Pier 1 Imports, told The Huffington Post that when her doctor instructed her to adjust her work schedule and not "lift more than 15 pounds or climb ladders" anymore, her boss put her on "light duty" for eight weeks. After those weeks, he placed her on a permanent leave, even though California law prohibits employers from placing pregnant workers on leave when they have not asked for it.

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act would protect women from this type of discrimination. The act was first proposed by Democrats in Congress in 2012 and reintroduced in 2013, and adds an important piece to the existing law requiring employers to make workplace accommodations for expecting mothers; it bans employers from forcing pregnant workers to take unpaid leave when other accommodations are available.

2. Pass the Family And Medical Insurance Leave Act (FAMILY) Act.

Once those babies are born, parents still need some workplace exemptions. A Pew report found that the need to care for a child or another family member has prompted 42 percent of mothers to reduce their work hours and 39 percent of mothers to take significant amounts of time off. American companies need to realize that people have families and, sometimes, those family members get sick. In those times, employees may need to take days off to care for a husband, wife or kids.

The Family And Medical Insurance Leave Act -- or FAMILY Act -- would offer any private or public worker an insurance plan that would guarantee them paid family leave. This would help take weight off the shoulders of the six percent of people who revealed in a Department of Labor survey that they need family leave but don't take it because they can't afford the unpaid days off. Any worker, whether employed by a private or public company, would have the option of applying for these benefits. The insurance ranges from a $580 monthly minimum to a maximum benefit of $4,000 a month, or 60 "caregiving days" within one year.

3. Implement paid-leave policies for all mothers and fathers.

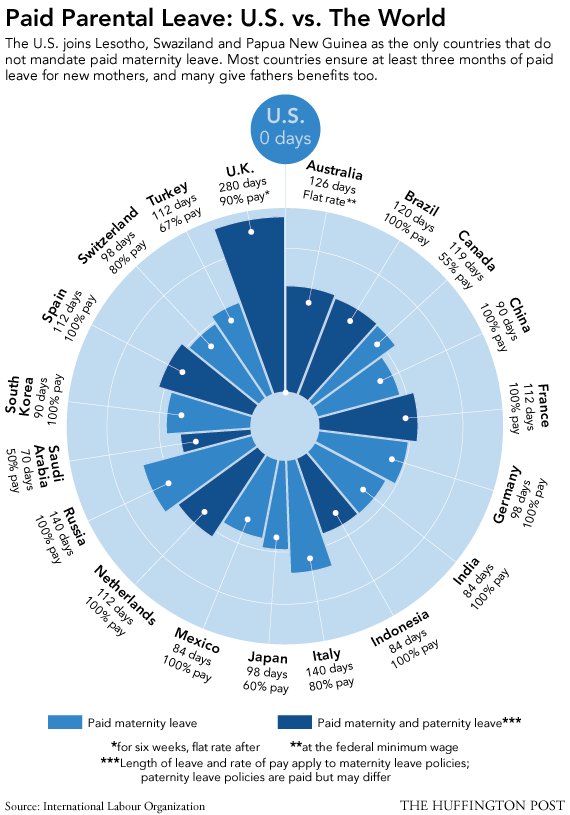

Guess how many days of paid leave are guaranteed to new U.S. parents. The answer is zero. The United States is now the only industrialized nation that doesn't promise paid maternity or paternity leave.

While U.S. law allows parents to take up to 12 weeks off without risking losing their jobs after the arrival of a newborn (due to the Family Medical Leave Act of 1993), other countries guarantee compensation for those missed days. For example, Brazil offers 100 percent paid maternity and paternity leave for 120 days. And having more fathers take parental leave helps mothers get back to work, a study by graduate student Ankita Patnaik at Cornell University concluded.

4. Create more affordable child care.

A report by Child Care Aware America revealed that in 31 states, the annual cost of daycare exceeds the average in-state tuition and fees at public colleges. The starkest comparison between daycare and college tuition costs is in New York, where daycare can cost up to $15,000 and in-state college tuition hovers around $6,500. One reason for the high price tag is that some states have very strict, government-mandated child care regulations that inflate daycare costs. The Atlantic reports that child care is subject to strict standards on the square footage needed per a child, as well as how many teachers can teach a certain number of students. For example, in Massachusetts, the state with the highest average yearly child-care cost at $14,980, child care centers must hire one teacher for every three infants.

But while the percent of family income spent on child care has remained constant in the last quarter of the century, the cost of child care has doubled. The expense has forced some parents who earn middle or lower-class incomes to choose between giving up their income entirely so that they can care for their children themselves, or take a huge portion out of their paycheck to pay for outside care. In 2011, for instance, families with employed mothers whose monthly income was $4,500 or more paid an average of $163 a week for child care, representing as much as 6.7 percent of their total family income. Families with monthly incomes of less than $1,500 paid much less -- $97 a week on average -- but that represented up to 39.6 percent of their family income.

According to a report by the National Conference of State Legislatures, employers say that child-care dilemmas cause more problems than any other family-related issue in the workplace and increase tardiness and absenteeism in nine out of 10 companies. Employers could help mitigate these problems by offering on-site daycare programs. Not only could parents get back to work, but they would be much happier and more productive. Rachel Connelly, the author of "Kids at Work: The Value of Employer-Sponsored On-Site Child Care Centers," interviewed 1,000 American employees (with and without children) and found the majority of workers were willing to take out between $125 and $225 from their paychecks to subsidize on-site daycare in their workplaces, even if they didn't have young kids themselves.

5. Take notes from France and offer subsidies to cover child care.

For many Americans, child tax credits and personal tax exemptions for children are the largest breaks available. One major issue with these tax credits is that they have an income-based structure, which often results in more assistance being provided to higher-income and middle-class families and no assistance provided to the poorest families, who sometimes do not file taxes at all. Another problem is that the credits make it hard for families to incorporate them into a stable family budget, since they are usually sent out as a lump, one-time payment during tax season.

The U.S. should take notes from France's government, which offers options to new parents in the form of affordable municipal day care, universal free preschool starting at age three and tax breaks for families who employ home child care workers. France also implements a flat, monthly child allowance to every family with kids. The basic family allowance provides every low-income family with a monthly childcare allowance during a child's first three years. Families with more than one kid receive a monthly allowance for each child up until they are 20 years old. That extra money could surely help American families pay for the current exorbitant daycare costs.

6. Make flexible work weeks the norm.

Early experiments conducted on four-day work weeks have suggested that it's possible for the average American worker to still productively log 40 hours a week while getting a whole weekday off. If all employers would allow people to coordinate their work schedule in a way that would accommodate their lives outside of work, valuable time would be opened up for hurried parents who are trying to make time for their families. Lisa Horn, the co-leader of the Society for Human Resource Management, told Forbes that a compressed workweek "is a great way to provide employees the flexibility to meet the demands of work and life outside of work."

With less stress comes more happiness. For example, when Utah implemented a four-day work week in 2008, productivity soared along with worker happiness. And an American Medical News report states that 44 percent of female physicians work less than full time, with one doctor saying does it so she can "have the freedom to spend more time with her two young children."

7. Give middle and low-wage workers the same flexible hours that high-wage workers get.

Income inequality goes beyond impacting the individual employee at an unfair company -- it also starts affecting their families at home. A Bureau of Labor Statistics' survey on American time use found that more than 90 percent of high-wage workers report that their companies allow them to take paid time off or change their schedules if a family emergency arises. However, less than half of workers in the bottom 25 percent of earners and about about half of middle-income workers said they were allowed to do so. A sick child or other obligations, like mandatory school meetings, shouldn't be harder to deal with for lower-income Americans.

8. Realize that working moms can still be effective moms.

The number of moms who'd like to be working full time may have increased, but it would appear public opinion hasn't shifted quite as much. Among all adults surveyed by Pew, only 16 percent said they think it's best for a mother of a child to work full time outside the home, and one third of those surveyed still think it's the ideal situation to have a mother who does not work at all. It's surprising that so many Americans feel this way -- in a Pew report from 2013, 75 percent of Americans said they agreed that "a working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work."

Why the disparity? Jerry Jacobs and Kathleen Gerson, professors of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and at New York University, told Time that according to their findings, Americans generally agree with the idea that mothers should be able to work outside the home, so long as their outside life circumstances fall in line with society's image of a good mother. They found that people supported the idea of working mothers as long as the mom had good child care, enjoys her job and actually needs the job to support her children. They did not agree that a good mother works if her child care is poor or she is working without actually needing to.

But studies indicate thinking that way is wrong. A recent study conducted by U.S. and Denmark researchers concluded that among 135,000 Danish children, from birth to age 15, those with part-time working mothers do better in school than those who had unemployed mothers. The researchers compared each child's GPA at age nine with his or her mom's work patterns during the first three years of the kid's life, and children whose mothers worked between 10 and 19 hours when they were under the age of four had grades 2.6 percent higher than a "similar" kid whose mother had not worked.

9. Abolish the stigma against stay-at-home dads.

More women today are likely to be their family's primary breadwinners than ever before, with a Pew report stating that four in 10 American households with children under the age of 18 have a mother who is the sole or primary earner in the family. Yet according to Census data, only 180,000 U.S. men stay at home, which account for only 0.8 percent of married couples in the country. This type of father is extremely rare, which will not help in lessening the negative stigma associated with this role.

When the Wall Street Journal asked their Facebook followers how they felt about fathers taking parental leave, younger fathers thought it was vital, while older fathers thought it created a bad reputation. When interviewing stay-at home-fathers for The New York Times, Jodi Kantor encountered one dad, Jim Langley, a former architect who decided to quit his job and stay at home to take care of their child because his wife made over half of his former salary. Langley said he is perceived negatively by others when he tells them what he does. Instead of lying, like some other stay at home fathers do (some say they are retired or that they work from home), Langley tells the truth and said that the response is "usually a long pause."

And while the media has been making some strides in changing the negative image fathers induce, Lance Somerfeld and Matt Schneider, write in a blog post for the Huffington Post, that advertisers and film and TV writers need to rethink how they paint the image of the "American dad." They write that much of media inaccurately portrays fathers as "buffoons" when in reality "it's all hands on deck just to keep up with sports practices, homework, PTA meetings, meals, and everything else that keeps a family and home running."

All photos courtesy of Getty.