Having escaped the confusions of childhood and emerged through the hot or cold war of your teenage years, you stride into the world feeling steeled against formative experience.

And then, into the blast furnace you go.

"A first job may be similar to one's experience with grade school," Larry Ragan wrote in a private memoir. "It becomes engraved in the memory."

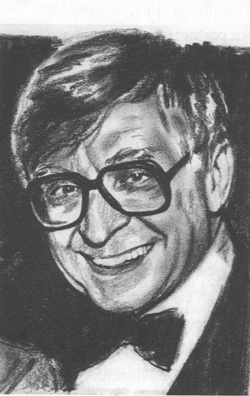

And since Larry was my first boss--he was the founder of the Chicago trade publisher Lawrence Ragan Communications--he is engraved in my memory.

Engraved in the hopeful, but suddenly fearful part of my memory that comes alive in the spring and remembers what it was like to be a young graduate lost in a world that had heretofore gotten along just fine without me--but a world that I needed to take me in.

Engraved in the hopeful, but suddenly fearful part of my memory that comes alive in the spring and remembers what it was like to be a young graduate lost in a world that had heretofore gotten along just fine without me--but a world that I needed to take me in.

The man who would become my first boss knew as well as anyone what that felt like; he had found his own way to meaningful work by traveling through a number of much dirtier, weirder, more anonymous workplaces than most of us can imagine today--that mostly lost world of urban manufacturing that so many of Studs Terkel's subjects spoke about, and sing about these days, in Working.

But did he tell me he understood exactly how I felt? Not until much later, and not in person, but rather through a memoir he wrote before he died.

Larry graduated from De La Salle High School in 1940, at the tail end of the Great Depression, and went straight to work for the Olson Transportation Company, typing bills of lading. He worked alongside a De La Salle classmate named Mike Bilandic, who would go on to become mayor of Chicago.

"We often laughed about the fact that we were two of the fastest typists in the De La Salle graduating class, so Olson was getting the very best," Larry recalls in the memoir.

***

Fifty years later, Larry's 12-person newsletter outfit had its own oddities and demoralizing obscurity.

"Let me get this straight," said New Yorker writer Calvin Trillin, once invited to speak at a conference Ragan was sponsoring. "You write newsletters for people who write newsletters."

Yes. We published instructional newsletters for editors of company newsletters. A pretty narrow literary vista for an English major straight out of college.

But actually it had been six awfully long months since I graduated, in 1991, the middle of the last big recession. During that time I had worked for a week as the "night waterman" at a public golf course. I had been turned down for an editorial assistant's job at Bowler's Journal because the other candidate had more bowling experience. And I had failed a one-day tryout as a door-to-door salesman of stuffed animals.

So I appreciated the job at Ragan Communications. But Larry had early reservations about me. "Callow," was the word he whispered about me after a meeting in which I had suggested, only a couple months into my time there, that on weeks that Larry didn't feel like writing his column in the flagship newsletter, perhaps I could fill in.

"I'm pretty creative," I remember suggesting brightly.

A painful memory, injected with some still-rueful mirth recently, as I reread the Larry's memoir and beheld the dues he had paid and the jangled trip he had taken to find a suitably meaningful professional niche.

After leaving the trucking company, Larry would endure 10 more bum jobs over more than 15 years before he found work that he considered worthy. And it would be 30 years before he started the publishing company that would be his legacy.

I imagine those years flashing before his eyes as I suggested that, fresh from James Joyce and Ezra Pound, I was ready to start suggested I was ready to start sharing space with him on the front page of the newsletter he had founded after so many years of optimistic, tireless but often hapless searching.

***

In 1941, Larry went to work as traffic clerk for a local oil company called Cities Service. When his boss there was drafted into the army, Larry took over his job, and a month later asked the general manager for the title of Traffic Manager, and a big raise.

"Responding, he quoted Napoleon to the effect that experience and age are what Napoleon looked for in his generals, and youth and vigor in his soldiers. I wonder," Larry added, "do general managers of oil companies quote Napoleon today?"

After his own stint in the service--bad eyesight relegated him to the Coast Guard, where his duty was easy--he resumed his unhappy search for a decent job in Chicago.

He got hired by the U.S. Dental Company, located in the triangular Coyote building at North, Damen and Milwaukee Avenues.

This company sold false teeth by mail. I worked as a sales correspondent. There is no other way to put it: I was dumb.

Was there nobody to tell me that surely, in the post-war booming year of 1946, there were better jobs to be had, better companies to work for? Evidently not.

The company had about 50 employees. It was owned by a lawyer whom we never met, and was run by a formidable woman of middle years who herself would not come in more than three times a week. Most of the employees worked in the laboratory, making the teeth. I was among a handful of clerks who selected form letters to respond to inquiries or selected different letters to respond to complaints. ...

It took me only a few months to realize that this work was not for me, so I gave a few weeks notice that fall. The general manager asked me to write her a memo making any suggestions for improvements to operations. I did so, though I have no idea what I said. I'm sure it must have been embarrassingly naïve. She never said a word after I gave it to her.

But a few months later, when I was already working for Gaylord Products Co., I learned that she responded to Gaylord's employment enquiry that she wouldn't rehire me because I didn't agree with the company's policies. So it goes.

Gaylord made bobby pins and hair pins and compared with the job at U.S. Dental, "Gaylord was strictly uptown," Larry remembered.

But that job didn't hold his interest either, so out of frustration, he enrolled at the University of Chicago at the age of 27, and escaped workaday Chicago once again to study English. At the highbrow U. of C., he recalled, "We felt removed from the rest of society. We were different, we were University of Chicago students. In the fall, after summers away, people would ask each other, 'How did you get along outside? Were you able to communicate?' Yes, obviously, it was silly and arrogant; but such an atmosphere was also heady--and fun."

The intellectual fun came to an abrupt end when he graduated in the summer of 1951.

I went to work with a manufacturer of gun barrels.

I'm glad I did, for working in that drudgery job for six weeks was an experience I would never otherwise have had. It was dreadful--the 12-hour days, the crushing boredom, the clock-watching, the joy that I experienced as I walked out the door when the day was over. It gave me a small insight into what many men must go through as they work in dull, repetitious, demeaning jobs.

On the first day, I was shown how to insert a rifle barrel into a vice, position a cutting wheel directly above the right spot, turn a small wheel with my right hand as I cut a small groove into the piece of steel. The foreman took two minutes to show me how to do it, then watched another four minutes as I did two or three. Two hours later he returned to tell me that I was working too fast.

[Wife] Jeanne enjoys recalling the wedding that she and I went to around that time. Making conversation, the priest asked what I did for a living. I responded, in all seriousness, "I'm a milling machine operator."

My career came to an end one rainy Monday morning. I couldn't drag myself out of bed.

After that came a couple of unsatisfying clerical jobs at publishers, and then a crack of daylight--a job as the editor of the employee newspaper at the huge Ford plant on Torrance Ave., a job that paid well enough to keep him there for four years.

But later, he would confess that he looked back at his days there and shudder at the eight to five routine:

"Maybe what I craved was the possibility of growth, of meeting new people, coping with new problems, working to solve larger problems with others. Instead, I was isolated, on the far southeast side of Chicago, the city limits, working in what came to be a corporate cog that was unfulfilling and, ultimately, dispiriting."

But that was the end of his factory life. In 1957, Larry took a pay cut to work in a more intellectually congenial environment, in the public relations department at DePaul University, where he also became an English teacher and picked up freelance editing work which he eventually parlayed into his own publishing company.

***

Though Larry's subject was ostensibly corporate communication, much of his writing was in one way or another about jobs, and work: how ambitious or patient, how clever or compliant, how idealistic or realistic should one should dare to be. It was a subject he always wrestled with publicly.

And privately too, I'm sure. Like, in 1992, when his son Mark hired a callow young writer who needed knocking down a peg.

So I worked the coat check at the company's conferences. I had the oldest computer in the office, and when it crashed, I unplugged it and lugged it several blocks to the repair shop. I worked on publications with dying circulations, and was assigned new projects with low status and dubious prospects. And occasionally the office manager would roust me from my editorial desk and send me into the basement storage unit to look for some dusty old book that a customer had ordered. I'd stand down there smoking cigarettes and thinking resentfully about this two-bit, crazy family outfit I was working for.

But Larry had managed to get me interested in his subject matter--at least, in his broader interpretation of it--and so I hung in there for a few years. I tried to quit once, and Larry, then suffering from Lou Gehrig's disease, saw to it that I got a generous raise and a new assignment. When Larry died in 1995, I was the obvious choice to edit his memoir, a copy of which his widow signed for me, with a note about Larry: "He liked you so much and thought you did a wonderful job."

That's nice to read even now, 16 years later, long having left Ragan Communications' employ, having written for various magazines and newspapers and other outlets about everything from ballet to boxing, politics to professional poker. And thanks to the good fortune of having started out in that odd little niche, I'm still writing about corporate communication, for bread and butter that freelance journalists without a specialty find hard to come by these days.

And because of the early guidance of someone who made me see the depth of the subject, I'm still enjoying the work.

So now I can laugh right along with my engraved memory of Larry Ragan about a meeting with Mike Bilandic, his old typing buddy at Olson Transportation Company, almost 40 years later.

"When he was mayor and attended a De La Salle alumni party for our class, I reminded him of our association at Olson--or asked if he remembered our working together--and he pretended that he did; and then had the nerve to ask me if I was still there."