It seems like every day there's a new report painting a grim picture of the impending FIFA World Cup that will take place in cities across Brazil next month. Stadiums and other event-related facilities such as airports aren't completely finished. Protests are still taking place. And many Brazilians seem to be unexcited, to say the least, about the worldwide spectacle that's due to take place in their country.

One of the biggest causes of the unrest? The unbelievably high figure Brazil has shelled out for the event... from public funds.

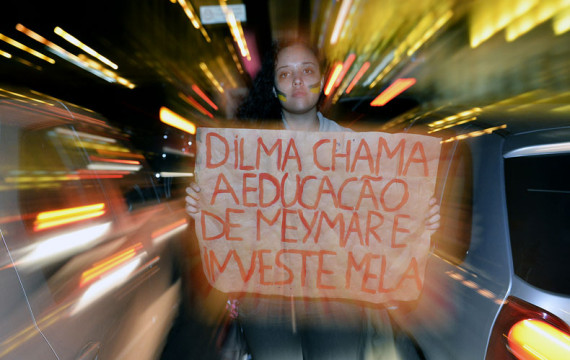

Neither the World Cup nor FIFA, its organizing body, are completely to blame for the frustration and indignation Brazilians feel over the looming event. Brazilians aren't gathering in the streets to protest one of the world's most popular sporting event itself, but are rather in the midst of a longstanding fight against the Brazilian government, which they believe has failed to deliver on promises to the people. It's a much larger strife for the most basic and simplest of human dignities, including education, healthcare and affordable housing -- many Brazilians feel the money would be better spent if invested in these social necessities.

Hidden in the numbers, or perhaps parading around in plain sight, is a sense of just how complex the situation really is. Here's a look inside why these protests, which started about a year ago, are still going strong, and why they are expected to carry on throughout the duration of the World Cup.

Brazil is expected to spend close to $11.7 billion on this World Cup.

When you realize that the billions spent come from Brazil's public funds, and all ticket and media rights revenues made from the Cup go directly to FIFA without taxation (which is true of every World Cup), the public unease seems inevitable.

The astronomically high cost of the tournament is the most pressing concern among Brazilians. With an expected final price tag of more than $11 billion, this will be the most expensive World Cup to date. South Africa spent about one-third of that in 2010, (close to $3 billion total) and was still the most expensive Cup at the time.

Many are worried the investment won't pay off. Estimates suggest that longterm revenue of about $25 billion will be pumped back into the country's economy, according to Brazil's tourism authority Embratur, part of the Ministry of Tourism. A number arrived at based on how much the 600,000 foreign tourists who are attending the World Cup in June are expected to spend. But not all are optimistic: South Africa never fully recovered from the billions it spent on the 2010 World Cup. According to the Associated Press, the country reportedly only made back $400 million of the nearly $3 billion spent, and Brazilians fear a similar fate.

Meanwhile, 55 percent of Brazilians feel that the event will do more damage to their country than good.

A recent study conducted by local Brazilian institute Datafolha revealed that more than half of the nation believes this World Cup is essentially bad news. That number is up 11 percent from Datafolha's last study, conducted in June 2013 during the Confederations Cup -- the tournament that takes place in the host country a year before the World Cup -- which showed 44 percent of the population believed World Cup would do more harm than good.

In a different study also conducted by Datafolha in 2008, a whopping 79 percent of Brazilians supported hosting the World Cup in their country, but that number has since dropped dramatically to 48 percent. Discontent over exorbitant public spending started brewing in the summer of 2013 as people took to the streets to protest both the Confederations Cup as well as the Cup itself. Thousands gathered in front of Rio's Maracanã stadium, where the protests eventually turned violent.

$900 million in public funds went to building a new stadium that will likely be "abandoned" once the tournament is over.

Brasília's Estádio Nacional Mané Garrincha stadium, which was inaugurated in May of last year and constructed solely for the World Cup, is now the second most expensive soccer stadium in the world. The budget for this particular stadium nearly tripled between the beginning and end of its construction, an outcome that most Brazilians attribute to corruption and fraudulent spending.

Even more unsettling is the fact that the city of Brasília does not even have a professional soccer team to use the stadium in the future. After Mané Garrincha hosts seven World Cup matches, there isn't a permanent organization in place expected to use the facilities. Yet when broken down by the numbers, almost ten percent of the World Cup budget was spent on this stadium alone.

Brazil's original plan was to host the World Cup in eight cities. Then Brazilian Football Confederation President, Ricardo Teixeira, pushed to expand it to 12, thus requiring completely new stadiums and an increased spending of public funds.

Other newly built arenas include Arena das Dunas in Natal at an estimated cost of $400 million, Itaipava Arena Pernambuco in Recife at $500 million and Arena da Amazônia in Manaus at $290 million. The latter, located in the damp Amazonian jungle, is considered to be the most controversial due to its isolation. Many are worried about what will happen to the stadium once the Cup is over. Manaus, like Brasília, also does not have a professional soccer team.

Eight workers have died so far in the construction and remodeling of stadiums across Brazil. The latest fatality happened just earlier this month as workers are hurrying to finish construction before the June 12 opening.

Over 250,000 families have been forced from their homes to make way for stadiums.

According to the Popular Committee of the World Cup, hundreds of thousands have been displaced from their homes in order to make room for new construction in areas surrounding the soccer stadiums. The government relocations due to the Cup as well as the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro are becoming all too common, especially in the Metrô-Mangueira area near Maracanã, the stadium hosting the Cup final.

Some of the displaced, forced to relocate, have been left completely homeless without any affordable housing alternatives available. By June, relocations in one slum alone will have affected 678 families.

Although there's some dispute as to why the forced removals are taking place -- residents believe it's to "clean house" and make room for a parking structure for the Cup, while some officials insist it's to construct an automative plant -- residents of the slum are comparing what once was their home to a distressed Libya or Iraq. Where once stood houses, most of them constructed with their owners' bare hands, now lies nothing but rubble and an unrecognizable landscape of what was.

The displacements aren't only affecting the poorest Brazilians. Others report being squeezed out due to higher rent rates in surrounding stadium areas, forcing them to seek alternative housing. A particularly large group affected in the country's metropolis of São Paulo responded by seizing an abandoned piece of land nearby. Since inhabiting the vacant land, the group has banded together as an improvised community.

"We are not against the World Cup," explained one resident to the Associated Press. "We are against how they are trying to belittle us. They are giving priority to soccer and forgetting about the families, about the Brazilian people."

Tensions are climbing as Brazilians also tire of a corrupt administration and police force.

At the center of the protests, ongoing in Brazil since June of last year, lie the people's demands for better education, health care, public services, the right to protest peacefully and a less corruptive governing body and police force.

Every year, police are responsible for over 2,000 deaths in the country and the beginning of this year proved no different, with fatalities including Cláudia da Silva Ferreira, an innocent woman who was killed after being dragged behind a police car, and Douglas Rafael da Silva, a well-known dancer on a local television show who was mistaken for a drug trafficker by police.

The three policemen involved in Ferreira's death have been responsible for at least 69 "on-duty killings" since 2000. Most officers attribute sporadic fatalities to suspects "resisting arrest," even if evidence suggests otherwise. These incidents have sparked more outrage and unrest in the country at a time when the relationship between its people and its government is already strained from the spending scandals of the World Cup.

In response to the general chaos, Brazilians have gone on strike, with groups of teachers and bus drivers leading the charge to demand change.

Bus drivers, teachers and military police are among the few groups who have frequently abandoned their posts across various cities in the past few months. Most recently in Recife, rioting and looting erupted this month after the military police had already been on strike for three days. Federal troops later entered Recife to help maintain and diffuse the situation.

Meanwhile, protests are intensifying. On May 15, 2014, 12 Brazilian cities carried out protests in a joint public display, one of the many the country has witnessed in past few months. Thousands took to the streets in São Paulo, Belo Horizonte and Rio de Janeiro.

Police fired tear gas and rubber bullets at a crowd of over 4,000 demonstrators near the Itequerão stadium in São Paulo, where the opening game between Brazil and Croatia will be held on June 12.

Meanwhile, independent groups are still organizing protests -- and vow to continue them once the Cup starts on June 12.

Although some expect Brazilians to ultimately embrace the celebratory World Cup atmosphere once the tournament begins, according to Brasil Post, close to 2,000 people have participated in organized demonstrations in the last six months in São Paulo. That's a significant drop-off from June of last year, when approximately 100,000 took to the streets. But certain groups, including the #NãoVaiTerCopa and Housing for All movements, have vowed to continue protesting even once the Cup kicks off.

Less than a month away, many Brazilians remain unhappy with the Cup -- and the unrest could carry over to the actual event.

Between Brazil running behind on World Cup infrastructure and citizens promising to continue their protests, many are anticipating a Cup of chaos and disorganization once the games begin.

On May 22, Amnesty International Brasil released a video calling for peace and "no foul play" during the World Cup. It shows protesters and police coming together on the field and engaging each other in what resembles the many violent protests that have taken place in the country over the event.

This is their second campaign about World Cup unrest, earlier this month they (virtually) gave 876 yellow cards to the Brazilian government for their handling of the protests.

The video closes with a very strong message and reminder to all those involved: "the world is watching."

Clarification: Language has been amended to indicate the Embratur is part of the Ministry of Tourism, but is not the ministry itself.