On a morning in February, less than a month into his presidency, Barack Obama walked onto a stage at a gym in Dobson High School in Mesa, Arizona, prepared to talk about the wave of home foreclosures wrecking neighborhoods across the county.

The plan Obama sketched out on Feb. 18, 2009 suggested a new use for taxpayer money: to pay mortgage companies to restructure those home loans held by struggling families. Together with a refinancing program, the plan would prevent "the worst consequences of said crisis from wreaking even greater havoc on the economy," the new president said.

Georgina Solis, a teacher's aide at the school, listened closely as she watched the speech on a TV in a classroom. Her husband had recently lost his job as a maintenance worker, and the family had fallen behind on their mortgage payments.

"I gave my vote to Obama because he's a new hope," Solis said in an interview at the time with the Arizona Republic. "I hope I'll be able to keep my home because of his policy."

But the clear path to recovery Obama described never materialized outside that Arizona gym. The president said that the programs he announced would help between 7 and 9 million families lower their payments and avoid foreclosure. As of the end of June, just 2.3 million had gotten assistance. That was just the beginning of the plan's shortcomings.

Many of those whose loans were modified, like Solis, now say they feel stuck. Their monthly payments went down, but they are still underwater, meaning they owe the bank more than their home is worth. They can't sell, and so they must deal with a cruel irony each month: paying an inflated mortgage on an investment sold to them as the soundest financial decision they could make, a must-have for anyone who wants to join the middle class.

Other homeowners say the mortgage company they turned to for help lost documents, didn’t return phone calls and otherwise turned what should have been a simple financial transaction into an existential nightmare, one that sometimes ended in an unnecessary foreclosure.

According to one recent academic study, 800,000 families were rejected improperly or booted from the government’s primary homeowner relief option, the Home Affordable Modification Program, or HAMP, as a result of errors or misconduct on the part of mortgage companies. Assuming four people per household, that means a population roughly equivalent to the entire metropolitan area where Obama gave his speech, including Phoenix, Mesa and nearby Scottsdale were wrongly pushed toward foreclosure.

“Just when I think it can’t get worse something else happens,” said Mary Diab, an Overland Park, Kansas homeowner locked in a three-year battle with JPMorgan Chase that began when she sought a medical forbearance after a car accident. Diab says she went through three different loan modifications only to discover that the bank had foreclosed more than a year before.

Depressed, Diab recently went to see her doctor. “I’m going to write you a prescription for 30 valium and write myself a prescription for having to hear this,” she said her doctor told her after listening to her story.

The failure of Obama’s plan to live up to its promise has hindered the economic recovery. Had the plan hit its targets, the foreclosure crisis “would be history,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. The housing recovery that began earlier this year would have begun in earnest in early 2011, and by now default rates would be back to historical norms, he said. Today, opinions are divided on how how long a full recovery will take, with forecasts ranging from one year to three.

As it is, while foreclosure rates have come down and sale prices gone up recently, about 1.5 million homeowners remain in serious default or foreclosure, according to Realtytrac.

More than 13 million homeowners collectively owe $650 billion more than their homes are worth.

“That is a serious weight on the economy,” Zandi said. “These households are struggling, homeowners are not spending, banks are leery of them.”

This turbulence has helped depress prices, punishing middle class Americans, who rely on their homes for the greatest part of their net worth. According to the most recent numbers available from the Federal Reserve, the value of this investment plunged 40 percent from 2007 to 2010, to $55,000.

The slow recovery has also held back employment, as millions of construction workers, mortgage brokers, electricians and others who depend on a robust housing market remain sidelined. Three of the states up for grabs in the 2012 election, Florida, Nevada and Colorado, are among those hardest-hit by the housing crisis.

Given the magnitude of the problem — a housing bubble inflated to planet-size by Wall Street and mortgage brokers, combined with many homeowners content to not ask too many questions — there’s probably nothing Obama could have done to fully prevent what was coming. But if Obama loses a close election to Mitt Romney in a campaign defined by the Republican challenger as a referendum on Obama’s economic stewardship, the president’s handling of the housing crisis might be to blame.

So what went wrong? Rather than meet the home foreclosure crisis with overwhelming force, as he had attempted to do with the $787 billion stimulus, Obama went with a hastily-constructed program created by his Treasury Department that attempted to walk the line between tough standards meant to keep irresponsible homeowners from benefitting and meaningful homeowner relief.

The relief plan was flawed from the start. Rather than buy up troubled mortgages directly — or provide tough oversight and strong penalties for noncompliance — the Treasury Department provided modest “incentive” payments and then watched from the sidelines as the mortgage companies botched the handling of hundreds of thousands of loans.

The plan also did little to address the financial hazard of plunging home prices, even though the president succinctly described the economic quandary underwater borrowers face: “You can’t afford to leave and you can’t afford to stay,” he said in Arizona.

Yet instead of offering a plan that would have allowed people to write off some of the inflated debt that they owed, the president announced that the huge mortgage companies the government had just bailed out — Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — would relax their rules about who could refinance at a lower interest rate.

This is like acknowledging that the river is about to overtop the levee, and suggesting that people stand on a single sandbag to avoid getting washed away. An interest rate reduction lowers mortgage payments, which for some borrowers, can indeed mean the difference between foreclosure and keeping a home. But it does nothing to address the underlying problem that the president had just acknowledged: the value of the house is less than what is owed.

There was, technically, a debt forgiveness option as part of HAMP, but mortgage companies weren’t permitted to consider it until they had tried everything else to get the payments down, such as extending the term of the loan. Even then it was a rarity — companies are paid based on the value of a mortgage, so writing-off some of that value didn’t make much economic sense. As of June 30, just 60,000 families had seen some of their debt written off as part of a government-sponsored modification.

Over the past year the question of whether banks should forgive debt as part of a modification has emerged as the single-most contentious issue in the housing world. Opponents, led by Edward DeMarco, the acting director of the federal agency that oversees Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which control more than half of all home mortgages in the U.S., say it isn’t fair for some families to get this benefit while other, more responsible homeowners, get nothing. They warn of widespread intentional defaults by people hoping to cash in on the taxpayers’ largess.

Advocates for homeowners argue that many families bought at prices that were fraudulently inflated by Wall Street banks, which ignored the quality of the loans they were packaging and selling in order to collect big bonuses. (Allegations repeated in recent high-profile government lawsuits against Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase). Why should these banks get bailed out while homeowners get kicked out of their homes, they argue.

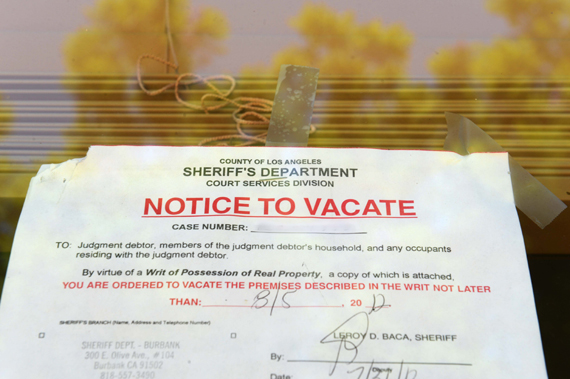

A “Notice to Vacate” is seen in the window of a foreclosed home in Glendale, California. (ROBYN BECK/AFP/GettyImages)

They point to studies that have also shown that principal forgiveness lowers foreclosure rates, which is good for everyone — including the taxpayers, which now essentially own Fannie and Freddie.

At ground level, perspectives differ. Some homeowners are simply happy they got some relief, and figure they can always sell in a few years when prices recover. Others say their homes are worth so much less than what they paid that it seems likely that their modification is just a stay of execution.

Solis fits both categories — she is grateful, but also worried. Her home loan was modified with little fuss by her mortgage company, First Franklin, she said in a recent phone interview. The monthly payments dropped dramatically, to $786 a month from about $1,400 a month.

But though Solis’s interest rate was lowered significantly, nothing was done to reduce the balance of what she owed on the mortgage. She is making payments on a $202,000 mortgage. The house is now worth $93,000, according to Zillow, an online real estate website.

In 2014, Solis’ payments will begin to go back up again under the terms of her modification, unless Bank of America, which acquired First Franklin, restructures the loan again.

The house is also infested by termites.

So the family faces a quandary. Do they invest thousands of dollars to repair a home they may not be able to afford to keep in a few years? And does it make sense to keep paying a mortgage when they have little hope of building equity?

“We are blessed,” Solis said. “But also trapped.”

REASON TO BE AFRAID

Obama took office in the midst of an economic freefall not seen since the Great Depression.

In January 2009 the economy hemorrhaged 741,000 jobs, the biggest decline in 59 years. Banks that had gotten a massive taxpayer bailout in the wake of the collapse of Lehman Brothers were still teetering on the edge of collapse. Home prices had lost 29 percent of their value over the previous year. Obama’s housing recovery plan was meant to work with the stimulus — which he had signed the day before — to staunch the bleeding.

Yet the Treasury Department, which shaped the housing relief plan, was worried about going too far. According to the published accounts of former administration insiders, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner was convinced that bailing out irresponsible homeowners would encourage future bad behavior.

That fear shaped Obama’s rhetoric and ultimately the programs themselves.

“The plan I’m announcing focuses on rescuing families who have played by the rules and acted responsibly,” Obama said sternly, at the Mesa speech. It would not, he said, “rescue the unscrupulous or irresponsible by throwing good taxpayer money after bad loans.” Nor would it help speculators who took risky bets on a housing market, dishonest lenders or people who bought homes they knew from the beginning they would not be able to afford, he said.

It was an impossible goal. Weeding out those who had bought a far more expensive house than they could afford from those who fell on hard times because of a job loss or some other misfortune was an impossible goal to achieve. Modification decisions, when made correctly, were based on hard economic data, such as whether an applicant had a job and could afford modified payments — not moral grounds.

If he was hoping to forestall right wing criticism of the plan, it didn’t work. Later that afternoon, Rick Santelli of CNBC called for a “Tea Party” gathering in Chicago to protest the president’s plan, which he said would “subsidize the losers’ mortgages.”

The plan Treasury crafted was meant to limit the government’s role in the process. Rather than buying up troubled home loans and then working with borrowers to restructure them, as the federal government had done during the the 1930s under Franklin D. Roosevelt — and as Republican presidential candidate John McCain had proposed during one of the debates — the Treasury Department would use Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, bailout money to pay mortgage companies to restructure loans at a lower cost.

The choice to use TARP money made sense given the politics at the time. The previous fall Congress had essentially written the federal government a $700 billion check to spend as it saw fit to save the economy from a complete meltdown. Using money already earmarked for economic relief without having to create a new government institution likely seemed an attractive option for an administration that had just passed its stimulus bill without a single Republican vote.

But the decision to essentially turn over administration of the programs to understaffed and undermotivated mortgage companies was a tactical disaster.

Many of these companies, known as servicers, were arms of the same banks that were bailed out with little vetting and few strings attached a few months before. Under the Obama administration’s plan, homeowners would not enjoy the same relief as the banks. Instead, they would essentially need to apply for a loan all over again, with all the paperwork and headaches that implies, and survive a “trial” period that was supposed to last three months but often dragged on for a year or more.

Sheila Bair, the former head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., writes in a new book that requiring each borrower to prove that he or she could qualify for a new loan was “stupid.” Given the large number of loans that needed to be reworked, as well as the problem of ill-trained and understaffed servicers, she said, “the cumbersome process was doomed to failure.”

The process didn’t work for Aracelli Davis. In 2010 her husband Ronald, who has Huntington’s Disease, tried to kill himself in the family’s Apache Junction, Ariz. home.

Davis had quit her job at a daycare to care for him, but after the suicide attempt she was forced to move him into a nursing home, she said in an interview, her voice quavering. The $632 in disability benefits she had drawn for caring for her husband stopped, she said. She fell behind on her mortgage payments.

The family was then “dual-tracked” by Bank of America, she alleges in a lawsuit against the bank. That meant that even as she was applying for a loan modification, the bank was proceeding with a foreclosure. In May 2011, Davis said a woman in the bank’s mortgage department told her that everything was on track for a modification. “Don’t worry, we have your papers and will call if we need something,” Davis said the woman told her.

Two days later Bank of America sold the house at auction. Davis had five days to pack up her two kids and all of their possessions and leave. Her son, who is autistic, was traumatized, she said. Bank of America declined to comment on the case, it said, because the lawsuit is pending.

I’ve heard some version of the Davis story probably 100 times in the past year from homeowners who lost their home or are on the brink of losing it because of what they claim are mortgage company errors. Some of these people made foolish borrowing decisions. But most are ordinary people who fell behind on their payments after they lost their job or got sick. They are at their wits end — they cry themselves to sleep, fret over their financial future and some worry about having to move into their car.

And they have reason to be afraid.

A worker removes furniture from a foreclosed home in Richmond, Calif. (JUSTIN SULLIVAN/GettyImages)

Large banks have proved so bad at preventing foreclosures that even Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac don’t trust them to do it.

Over the past year, Fannie and Freddie, which hire mortgage companies to manage millions of home loans that they own, have paid Bank of America and others $1.5 billion in kill fees to cancel servicing contracts for 700,000 loans. The mortgage giants determined that by moving the handling of these loans to specialty companies with a track record of communicating with struggling borrowers, they could prevent thousands of foreclosures, saving between $1.7 billion and $2.7 billion over five years.

The mortgage companies have borne the brunt of the blame for the failures, but all this happened under the watch of the Treasury Department and regulators like the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which for years failed to take meaningful action against the biggest banks over servicing practices.

“Servicers have been allowed to run roughshod over homeowners, with no consequences,” said Diane Thompson, a foreclosure expert at the National Consumer Law Center. “As a result, the foreclosure crisis has been greatly worsened, with devastating consequences for individual homeowners, communities and our national economy.”

As part of a $25 billion legal settlement with the federal government and states, five large banks — Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citigroup and Ally Financial — agreed earlier this year to implement wide-ranging reform of their servicing practices or face stiff fines of up to $1 million per violation.

There are some signs that practices are improving. But a monitor of the settlement appointed by California Attorney General Kamala Harris intervened as recently as September to stop banks from foreclosing on homeowners being considered for a modification in that state — the same kind of dual-tracking that cost Davis her home.

THE ‘MORAL HAZARD’

Sometimes the toughest part of a journalist’s job is tracking down a person whose experience properly illustrates a story. Finding people who feel they have been screwed by their mortgage company, though, is distressingly easy.

“I’m not sure I believe in America anymore,” said a cab driver who picked me up at Los Angeles International Airport last month.

I hadn’t told him I was a reporter, much less one who frequently writes about foreclosures. I had just asked him how things were going.

The driver, an Armenian immigrant named Gagik, told me that he had a thriving business selling — improbably — fireplaces in Southern California, prior to the housing crash. When the business failed he began driving a cab to support his wife and two daughters, he said. He soon fell behind on the payments on the Burbank home he had paid $700,000 for in 2006.

His bank wouldn’t consider lowering the principal amount he owed, even though the home’s value had dropped to just $300,000, he said. “We needed help and they wouldn’t listen,” he said.

For homeowners behind on their payments and struggling to keep their homes, mortgage debt relief, or principal reduction, is the golden ticket. Most have heard of it, few have seen it. Almost all want it.

Geithner initially said forgiving debt wasn’t a priority. “This program was not designed to start with a principal reduction,” he said at a Congressional Oversight Panel hearing in Dec. 2009. “We thought it would be dramatically more expensive for the American taxpayer, harder to justify, create much greater risk of unfairness and our program was not designed to do that.”

This is the “moral hazard” argument. Writing off debt threatens the covenant between borrowers and lenders, and encourages those making their payments on time to default and cash in. If the phrase sounds familiar, it is because Bush administration officials, including then Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson, frequently used it in 2008 to explain why they failed to throw a lifeline to Lehman Brothers, the investment bank that gorged on subprime mortgages, then melted down.

When that decision threatened to ruin the economy, Bush officials pushed the TARP bailout through Congress, threatening financial armageddon should lawmakers fail to act. Banks eventually collected $245 billion with little vetting, and still owe $13 billion.

The biggest financial institutions are now even larger than they were before the financial crisis. Despite a new law that gives regulators the power to seize and unwind a “systemically important” bank, critics on both the left and right think TARP set a terrible precedent — that the government will feel pressured to save the banks again should it come to that.

“Moral hazard is a very real issue for principal reduction,” said Christy Romero, the special inspector general of the bailout fund. “But taxpayers funding any of these programs is a moral hazard. It will be one of TARP’s long-lasting legacies.”

‘WHIPPING BOY’

Last year, as part of the negotiations that would lead to the national mortgage settlement, the issue of principal reduction came up again. State and federal negotiators talking to the banks about penalties wanted some part of the deal to include mandatory loan forgiveness.

It’s not clear why the administration, previously ambivalent about principal reduction, now supported the idea. At the time the deal was coming together — the fall and winter of 2011 and into early 2012 — the Occupy Wall Street movement was at its peak influence. The protests, while relatively small, reflected broad discontent among Obama’s liberal base with his policies, which seemed to favor Wall Street at the expense of homeowners. (Bankers, of course, would take the exact opposite view).

Whatever the reason for the change in attitude, the administration had a problem: while banks were willing to go along with a mandatory principal program as part of a settlement, they actually own only about 10 percent of the loans they service. Most of the rest are held by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, or by private investors who bought mortgage bonds during the run-up to the housing collapse.

Whether banks can write down principal on loans held by private investors is something of a grey area — various banks interpret their servicing contracts in different ways. But there was no ambiguity about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loans. The two companies, which still owe taxpayers $140 billion from the 2008 bailout that kept them from collapsing, forbid principal write-downs on the loans they control, on the orders of Edward DeMarco, a career bureaucrat who oversees the companies as acting director of the Federal Housing Finance Administration.

Former colleagues describe DeMarco as a politically conservative housing policy wonk thrust due to unusual circumstances into a job that was supposed to be temporary, but has stretched on for three years. In 2010, Senate Republicans spiked Obama’s choice to appoint a permanent head to the agency, the well-respected former North Carolina banking commissioner Joseph Smith. They decided they like DeMarco running the show just fine.

In order to bring more pressure to bear on DeMarco, in January the Treasury Department announced that it would triple the incentives it would pay for each dollar of loan forgiveness offered by investors.

An official familiar with the internal debate over loan forgiveness said this move nearly forced DeMarco to capitulate.

“DeMarco was getting constant calls from Treasury and the White House,” this official recalls. “It was a full court press.”

Yet DeMarco ultimately refused to yield. After months of signalling his clear distaste at the thought of debt forgiveness, DeMarco wrote a letter to lawmakers at the end of July restating his formal opposition. It was the moral hazard, he said.

“This could give borrowers who are current on their mortgages a message that the government endorses forgiving a portion of mortgage debt if hardship can be demonstrated, creating a very broad incentive for underwater borrowers to seek ways to become eligible,” he wrote.

DeMarco has declined repeated requests by Huffington magazine for an interview, but supporters say he just doesn’t think principal reduction would do much good, and that he fears it could undermine the confidence of the investors who buy the loans that Fannie and Freddie sell on the secondary market.

For his stance, he has become the unlikely boogeyman of the housing crisis. An activist group that represents underwater homeowners recently protested outside his Maryland home and attempted to deliver him a “pink slip,” suggesting that he should resign.

Geithner, who had previously expressed many of the same reservations as DeMarco about loan forgiveness, wrote him a letter expressing his disappointment with the decision.

To many outside observers, this about-face by the Obama administration, particularly Geithner, carries the strong whiff of hypocrisy.

“DeMarco is the designated administration whipping boy,” said David Felt, the former head of conservatorship operations at FHFA. “They know at Treasury that he is right on the policy, but politically that is not a position they want to defend. It is easier for them to say we support writedowns but this damn person won’t get out of our way.”

Barofsky, the former TARP inspector general, wrote recently that Geithner’s newfound embrace of principal reduction looks an awful lot like “political posturing.”

MYTHOLOGICAL ASSUMPTIONS

The tough part about rebutting the moral hazard argument is that some homeowners probably would stop paying their mortgage in order to cash in on the government’s largess. Others who would get the help don’t really deserve it.

I spoke with a housing counselor in Florida not long ago who told me that the only client she had that had gotten debt relief, out of dozens, was the one who had made the most foolish gamble on buying his home.

But there simply isn’t much evidence to support the prediction that masses of homeowners will take a gamble on their most valuable possession in order to possibly lower their balance.

“I think the spectre of ‘moral hazard’ is an ideologically driven fear built on mythological assumptions about people in economic distress and their willingness to hurtle themselves into foreclosure so they can try to game the system,” said Joseph Sant, an attorney at Staten Island Legal Services in New York, expressing the sentiment of many supporters.

Meanwhile, much evidence suggests that principal reduction actually prevents foreclosures and saves investor money. Re-default rates on the small number of mortgages modified with debt forgiveness under the Home Affordable Modification Program are less than half what they are program-wide.

Remarkably, even DeMarco’s own data suggests forgiving debts is a good idea. At the same time that he announced he was rejecting principal reduction for good, his agency released a report that showed it could help save the taxpayer as much as $1 billion, and the companies up to $3.6 billion.

What does Obama think? He has, in the past, acknowledged that the foreclosure problem was more significant than he anticipated, and the programs he promoted less effective. But on the campaign trail he has been silent.

Surprisingly, Romney has failed to exploit this vulnerability. In a housing plan released on his campaign web site, Romney said he would “spare thousands of families from going through the foreclosure process” by making foreclosure alternatives easier, but included no details on what he would do differently. Previously, during the Republican nominating process, he had said that he thought the best course was to let the market work it all out.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment. Neither did Geithner. But in July, the Treasury Secretary, who has said he will leave at the end of Obama’s first term, whether he wins reelection or not, spoke to Charlie Rose. Rose asked him if there was anything else the administration could have done to stop the foreclosure crisis.

In his response, Geithner blamed Fannie and Freddie for not moving earlier on the program that allows some underwater homeowners refinance at a lower interest rate. He didn’t mention the more prominent modification program, and he didn’t mention principal reduction. All in all, he said, the administration had done what it could with the tools it had, he said.

“Our job is to make sure that we are operating at the frontier with the tools we had, he said. “And I believe we did that. I really believe we did that.”

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.