This is the first in a 7-part series on women artists and writers who cross the homosocal divide. The series consists of Part 1: Women's Hidden Homosocial Past, Shirin Neshat, Laila Essaydi, Deepa Mehta, Marina Abramovic, and Angela Ellsworth. Part 2: Gender As Performance & Script, Yvonne Rainer, Sarah Charlesworth, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler. Part 3: Women's Art of Renewal (Disseminating New Codes and Enculturations): Carrie Mae Weems, Vanessa Beecroft, Sharon Lockhart, Catherine Opie, and Lisa Yuskavage. Part 4: From Victim to Victor, Women Turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out: Artemesia Gentileschi, Käthe Kollwitz, Frida Kahlo, Judy, Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Ana Mendieta, Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Janine Antoni, Kara Walker, and Sue Williams. Part 5: Did Men Invent Art to Become Women? Must Women Become Men to Make Great Art? (Leveling the Gender Divide) Sherrie Levine, Deborah Kass, Collier Schorr, and Jenny Saville. Part 6: Women's Mythopoetic Art: Going Back to Start, Heroically. Marina Abramovic, Louise Bourgeois, Nancy Spero, Mariko Mori, Shahzia Sikander, and Claudia Hart. Part 7: Women Looking at Men Loving: Eve Sussman, Kathryn Bigelow and the Women Writers of Mad Men. Part 8: Contra Acte: Mimi Smith and Susan Bee Unleash the Comic Repressed.

Part 1: Women's Hidden Homosocial Past

Artists never need to be told that objects and pictures are what matter in the compilation of history. Artists, after all, have historically bequeathed the most capacious evidence for the evolution of societal values, norms, and cultural codification spanning tens of thousands of years--with the last three to four thousand comprising a near-continuous narration of human sexuality and gender.

Art, in fact, has historically accompanied, if not at times precipitated and contributed to, the upheavals of tribes, states, and civilizations. It's only to be expected that art also plays a decisive role in the dissemination, legislation, and perpetuation of sex and gender codes. That's why, in looking back on the art of history, we can find clear evidence for the history of what in the last few decades has become conceptualized as the homosocial divide of civilization. By this I mean the cultural and geopolitical halving of humankind based not on gender difference alone, but as well by the presumed non-sexual, yet no less compelling, same-sex attractions cementing the alliances constricting power and privilege according to a culture's dominant XY (male) or XX (female) chromosome preference. In simpler terms, today's art is consciously being informed by what it always unconsciously reflected: the near-compulsory comfort found by men socializing exclusively with men and women exclusively with women.

It requires a survey of art made over great spans of time and geographic distance for us to see the evolution of the homosocial divide unfold. Of course, seeing is always selective, and like all other seeing, seeing the homosocial dynamics between men and women inversely rise and fall with regard to each's relationship to power involves selecting the right works of art from the right epochs in time. Yet when searching out the history of the homosocial divide, we can select any number of works from around the globe, especially in those civilizations with extensive artistic legacies. We will invariably find ourselves watching the same story unfold in Japan as in England, Greece, China, and Iran. But the story becomes even more richly laid out when we consider world art as a whole. Once key works of art made across the millennia and the globe are pieced together in chronological progression, we see with our own eyes the evidence for the two diametrically opposed yet inversely related narratives of power and gender that feminist historians of the last two centuries have been advancing as theory. And that's because feminist historians have themselves been deriving their hypotheses largely from the evidence of art that has been at hand. The difference in our study of the global homosocial history, of course, is that today we have the world's art extensively archived on the web. We are for the first time in possession of a world view that, though still far from culturally comprehensive on the level of indigenous societies, is at least representative of the dominant cultural powers that inform global civilization today.

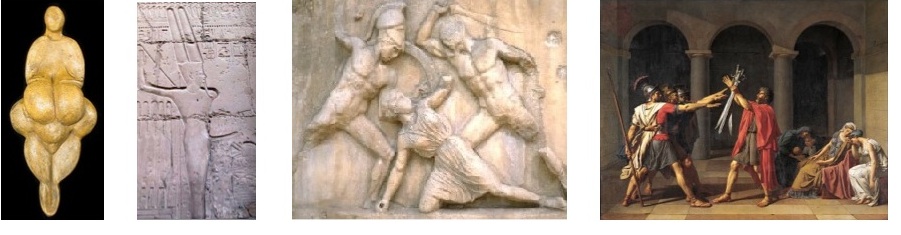

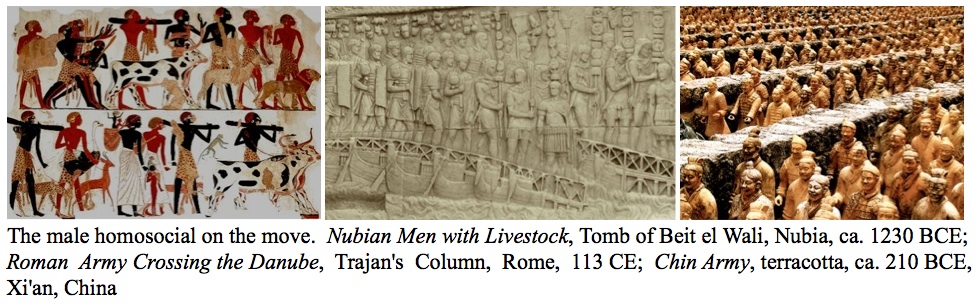

Take the four images immediately above this paragraph. (1) In the first photo, we see a small, portable Paleolithic stone sculpture that archeologists have come to fondly call a "Venus figurine." This particular figurine is known as the Venus of Lespugue, and is dated to ca. 24,000 BCE. Endowed with the anatomical contours of pregnancy, a number of these Venus figurines have been found throughout Europe and Asia. This suggests that the body of Woman was exalted by an array of nomadic hunter-gatherer societies that designated the female body representative of the Solo Creatrix of Life in a time hypothetically preceding "the discovery of paternity." (2) With the development of Neolithic settlements and animal husbandry, a new sedentary art begins to depict phallic gods, like this bas-relief of the ithyphallic Egyptian god Min found at Karnak, and dated ca. 1300 BCE. The new emphasis on the male and his penis suggests a shift in gender valuations consistent with the discovery of paternity which would have resulted in the new domestication and breeding of animals. In the succeeding centuries, father-creator deities gradually come to completely displace creation goddesses. By the Iron Age, the Greek drama, The Oresteia, proclaims there are no mothers, only feminine incubation vessels for the life-bestowing male seed. (3) This marble frieze of Greeks defeating an Amazon, from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus and dated 350 BCE, could be the result of a persistent defiance and uprising of women against male law that required women be put down in art as in life. (4) And with his keen interest in reviving depictions of political antiquity that mirrored the events of the French political and social events of his lifetime (here the events leading to the French Revolution), the painter Jacques-Louis David in 1784 painted his renowned Oath of the Horatii, which for us today appears every bit the crowning icon to the triumph and history of male dominion over the homosocial divide it was taken for granted to reinforce and perpetuate in its day.

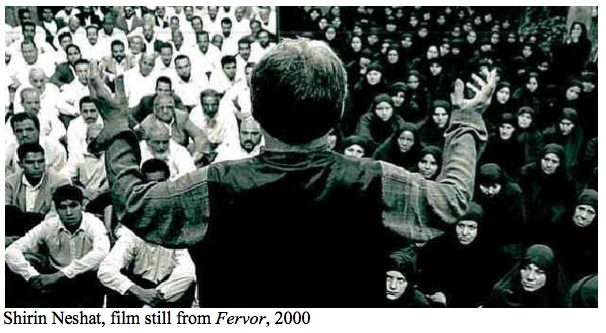

That this homosocial--be it chromosocial--divide has been largely legislated by men for at least four millennia has been amply commented on by feminists in a critique of patriarchy. But the notion of "patriarchy" proves insufficient as an account of the mysterious solidarity of men. It lacks comprehension of the features that bond men to men--and women to women. Meanwhile, the most vital art by women is making a seemingly hard biological fact like gender appear as a pliable and transposable tool of the individual will. That artists accomplished this well before the notions of "the homosocial divide" and "fluid genders" were embodied by compelling theory is testament that an artistic avant-garde not only still exists, but that women artists today own the propensity for being that avant-garde unto themselves. We need only consider the reactions of orthodoxies around the world to the homosocial art of women--whether it be the Hindu mobs in India who burned down the movie sets for Deepa Mehta's Water; the condemnation by fundamentalist Muslims of Shirin Neshat's photographs and film installations indicting the male abuse of Sharia law to constrict gender roles; the Religious Right's abhorrence of Catherine Opie's photographs of well-adjusted lesbian couples with children; or the feminists who too quickly reprimanded Vanessa Beecroft for parading and posing assemblies of female models nude but for the fetishistic trappings of make-up, wigs, and 6-inch pumps, while neglecting or resisting Beecroft's indictment of women's homosocial complicity in the commercial exploitation of their own bodies.

It's not merely a matter of art mirroring a homosocial organization of gender operative outside it. On the contrary, artists of the last four decades have done nothing if not shown to what extent art itself is a system of valuation, codification, and cultural perpetuation among which gender judgments count prominently. Then too, the homosocial divide isn't merely the simple bifurcation of human socialization it appears. It's a structural organization of society's possessions, mobility, and governance meshing every strata of civilization and the human primordiality beneath that stratification, while on the surface it performs as a theater of legislative proscriptions and prescriptions. What's important here is that through a study of art history up to and including significant contemporary production, we can access and trace the events at which political and ideological structures change. In short, we can demonstrate that to a large degree the sex and gender codes we've inherited are constructed on a political, superstitious, and arbitrary negotiation of the simplest 1-to-2 odds--human governance by all XY chromosomes (patriarchal), or all XX (matriarchal), or an historically rare XY-XX mix (democratic and various tribal societies) over the affairs of polity.

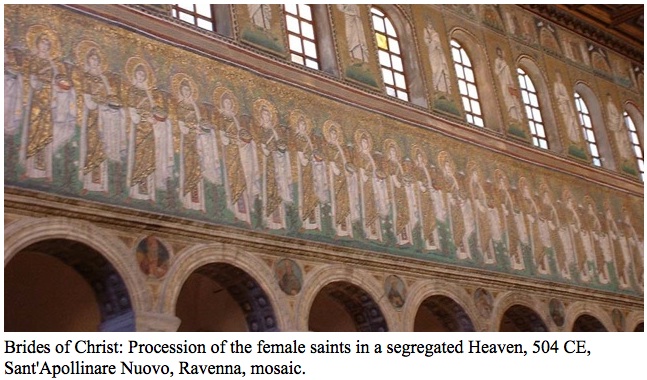

Such cultural transparency in art functions in large part as a theater of behavioral reinforcement, which makes the codes enhancing social position ideally suited for conveyance through art as a formal (pictorial, spatial, temporal) organization of ideas, objects, actions, and relations. But insofar as the social is theater, the homosocial has historically (at least for the last three millennia) played out largely for the benefit of the audience comprised of the culturally dominant gender chromosome, even in the historical enclaves of homoerotic societies. Still, for both dominant and submissive players, the homosocial is a performance removed from individual will in that both XX- and XY-chromosocial roles are kept confined to the scripted scenarios of masculine and feminine behaviors written for them centuries, even millennia, before their inheritance.

If the contemporary art of women surveying, crossing, and chipping away at the homosocial divide, like the art of feminism from which it grows, at times refers back to various points in the 4,000 years of male homosocial history from which these scripts emanate, it's because women artists actively partake in the eroding of a homosocial divide and the destabilization of anachronistic gender codes that built up at least from the Bronze and Iron ages. Then, too, these are the same living codes that continue to legislate against gay marriage, women's parity, and motivate the War of Terror waged by the enemies of modernism and democracy. It's why we find so many women artists move the clock of civilization forward by looking back to the epochs through which the paralysis of homosocial laws set in and spread through world cultures, thereby exposing the pretexts to domination that still operate beneath the artifice of anachronistic faith, government, custom, and art. It may be our greatest irony that as we become more modern and global we also revert back to a greater naturalism and individuation of sex and gender orientation denied humankind with the rise of the first cities and the warfare, economies, and social divisions assumed to defend and sustain them.

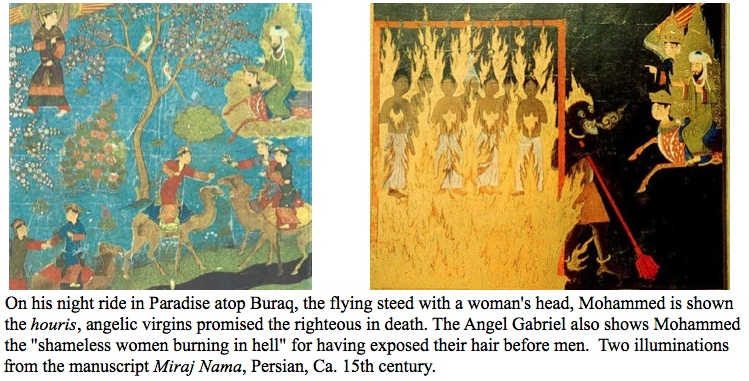

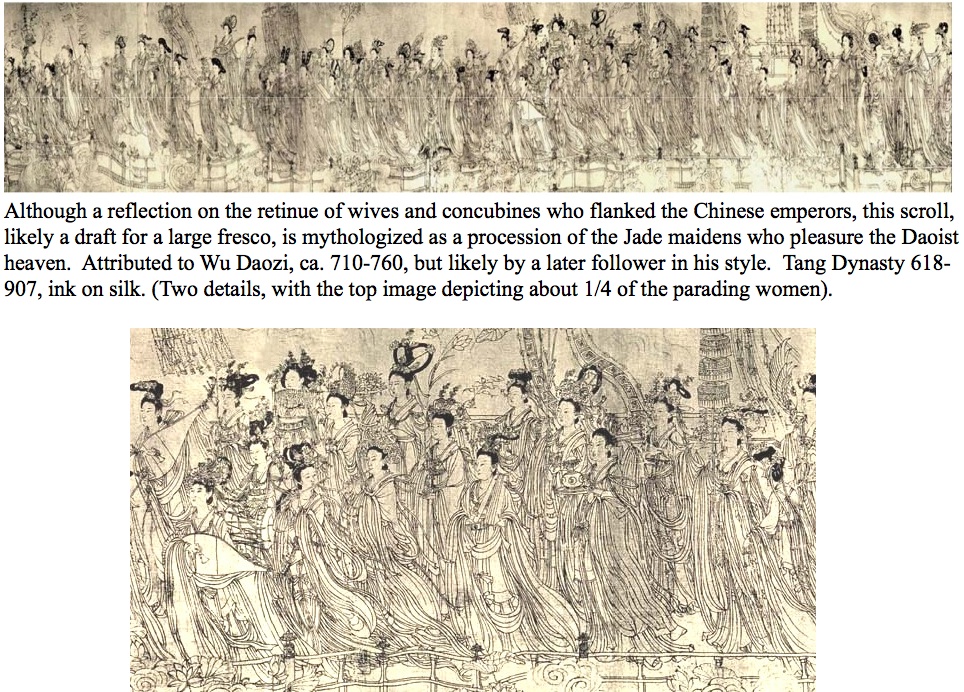

It's through art history that we see what contemporary art can only suggest: how art over time promotes cultural codes, and as part of its historicizing and status-raising functions--the very functions that make art attractive to the affluent and powerful--art normalizes and perpetuates the specific conventions for a society's arrangement of sex and gender relations and the objects accorded them by the requisites of the dominant homosocial order. We may find such sex and gender codes discreetly embedded--as they are in Chinese Tang (618-907 CE) and Song (960-1279 CE) dynasty scrolls depicting members of the scholar class traveling across a wilderness of mountains and streams. Only the initiated viewer recognizes the entourage sketched whimsically in isolation as the male-only company of the Chinese poets, artists, scholars, and nobles it invariably was, and as such conveying the predilections of the Tang and Song imperial and noble courts for the homoerotic and homopolitical representations they were sometimes intended to be.

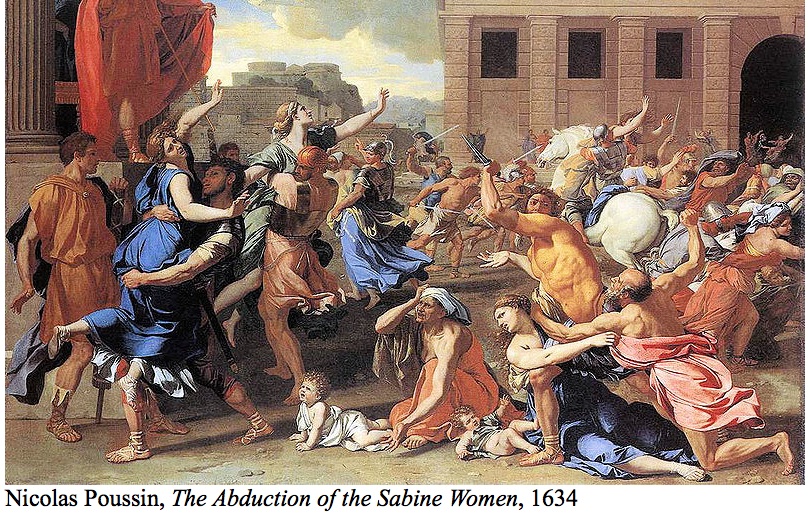

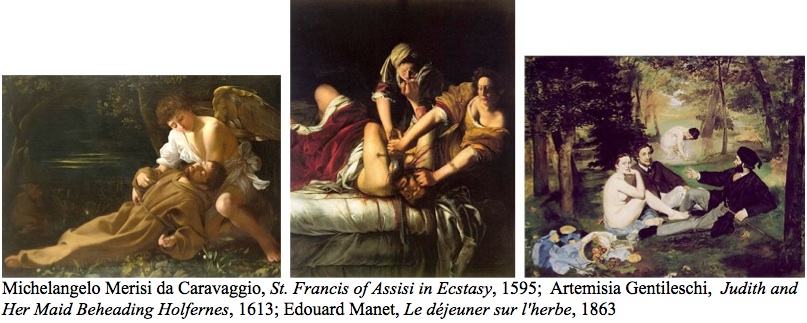

Or the code can be brutally direct, as it is in Poussin's The Abduction of the Sabine Women, whereby the artist constructs a theater of heterosexual rape with a pictorial homosocial subtext--filling the space intervening between male figures with the commutable spoils of swords, horses, and--yes--women, signifying an apparent hetero-male structure of commodity overlaid an otherwise evocative, but implicit, homoerotic voyeurism and phenomonology. With the rare but significant exceptions found in the art of homoerotic cultural representations, the encoding and organization of male homosocial gender values through pictures and statues was historically so taken for granted, it didn't require discussion until the codes were broken. We see this in Baroque Europe, with Caravaggio's "effeminate" St. Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy (1595) swooning in the arms of a buff male angel. We see it again in Artemisia Gentileschi's amazonian Judith and Her Maid Beheading Holfernes (1619). Both of these paintings scandalized their contemporaries by transgressing the gender proscriptions of the day.

We should also consider that what made Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) so shocking wasn't merely its portrayal of the overt male homosocial pleasure of sharing nude women sexually. That, after all, was established pictorially in Europe by artists like Poussin, in The Abduction of the Sabine Women, and Rubens, in Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus. As for the women's nudity: in déjeuner Manet doesn't just facilitate "the male gaze" as much as he symbolizes women unfettered by the male restraints of history and religion while recommuning with a nature from which women have been removed since preclassical times. It's Manet's portrayal of defiantly free-thinking women homosocially sharing men in déjeuner that is striking for its time, as is his stripping of the virility and heroism from the bourgeois men bequeathed them by Poussin and Rubens. The two men are seen as passive and even timid and prudish in comparison with the active and willful women of déjeuner, and the implicit homoeroticism of men "sharing" women that is concealed in Poussin's and Rubens' group rape, and the voyeurism of the male patrons for which the paintings were intended, is here brought to the surface.

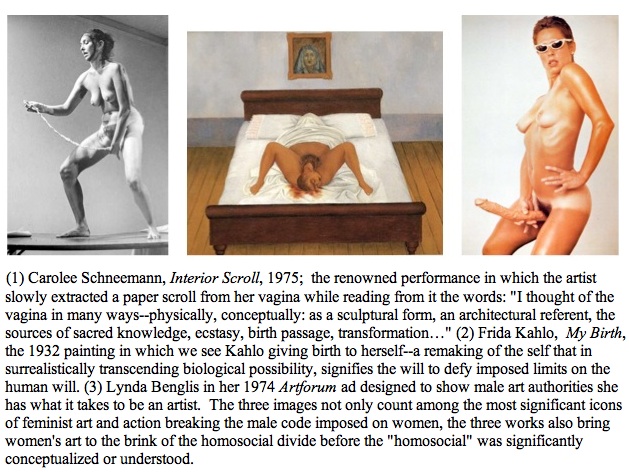

But Caravaggio, Gentileschi, and Manet are rare representatives of art's rogue disregard for the conventional role of art in the reification and perpetuation of gender codes. We mustn't confuse art's proclivity for sexual scandal (its function as pornography), which is common, with a willingness to disrupt the male homosocial gender codes, which is exceedingly rare. Far more often than breaking homosocial codes, the gender values conveyed by artists historically complied with, promoted, and legitimized the male homosocial status quo however unconsciously it was assumed and relayed by an artist to the public. Even after the rise of an avant-garde in the 19th- century, there are comparatively few stellar homosocial code breakers to celebrate prior to the 1970s--Egon Schiele, Frida Kahlo, Paul Cadmus, Francis Bacon, Kenneth Anger, Nikki de Saint- Phalle, Jack Smith, Carolee Schneemann, Andy Warhol, and David Hockney, among the few.

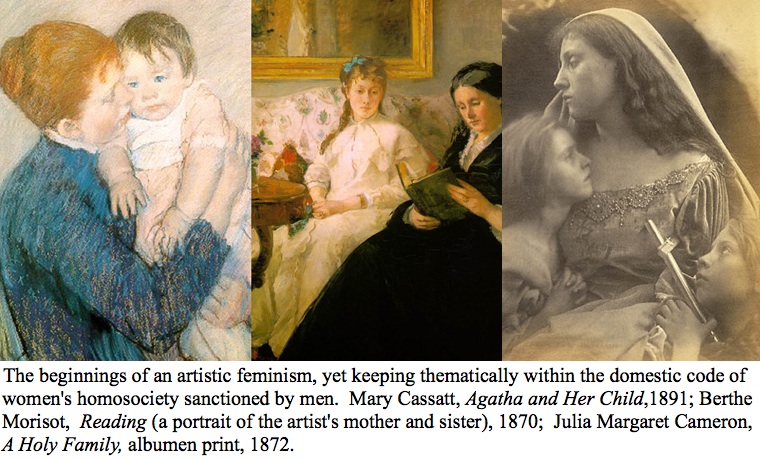

That all changes with the rise of feminism, which corresponds roughly with the expansion of the artworld to include women's production. Women's art began identifying women as separate and independent of men in their development and ownership of a unique signification and codification. Throughout the growth of women's art, feminist art and activism ferreted out and broke male homosocial codes while defining an activist women's homosociety. But though feminism brought women to the brink of the homosocial divide in identifying, exploring, and redefining the differences that produce the divide, feminism didn't mediate the deeper level of gender relations at which the bonds of homosocieties are cemented. That's because most feminisms reinforce women's homosocialization rather than cross, erode or dismantle homosocial boundaries and barriers. At this deeper level of human bonding, feminism merely mirrors the insularity of the world's masculisms rather than integrates with them.

That is until the early 1970s, when a significant few women artists and writers began to expand beyond the constraining significations and codes of feminism, femininity, and female homosocieties to exhume, examine, analyze, question, reshape, transpose, and conflate the notions and qualities of gender difference taken for granted by world civilizations. And because the best artists look beyond the limitations of their media, once gender became the central focus of some women's art--in a sense became the medium--artists also began looking beyond biological and cultural constraints. This expansion of vision renders the narrowly defined shibboleths, "patriarchy" and "matriarchy," insufficient for their neglect of the bonds of desire tying men together with men and women with women to form homosocieties. We now understand that both a non-sexual desire to be in the company of the same sex and a same-sex attraction form a similar bonding. Like homosexual desire, homosocial desire accounts for why heterosexual men flourish in their own company so well without women, while explaining how it is that women who are gathered together persevere objectification and subjugation so enduringly without more marked and frequent dissent. Residing at some core of the collective psyche theoretically prior to patriarchy and matriarchy, homosocial desire, while complimentary to but more ubiquitous and sanctioned than homoerotic desire, is the missing link of patriarchy and matriarchy in plain sight. It's a beguiling truism, but one that sets the pattern for platonic same-sex clustering not explained by sexual or familial desires. In studying art to trace our own culture's complicity with homosocial power structures, we begin to emerge from the gender constraints forged in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Yet when studying the art of historic and far cultures, we lack an eye for the encrypted codes and veiled histories investing significations and forms.

Particularly hidden in historic art more often than portrayed are the discreet and often ancient histories of women's homosocieties that foster women's resourcefulness and resilience. Of course, a discrete, innate, often secret, proto-feminism (the feminism that comes from the imperative within a woman for survival) circulated among women's homosocieties. This clandestine feminism was always there, saturating women's homosocieites with the will, if rarely the readiness, to break the male legislations and codes that kept women from empowerment. With the expanded economic and cognitive capacities that modernity facilitated, it became impossible to keep feminists from leveling and crossing the homosocial divide once women understood the codes and significations of feminism would themselves become constraining. Women began assuming roles and identities that required greater identification if not with men, certainly with trans-maleness, queerness and other alternate sexualities and gender conflations. In this sense women's homosocieties not only advanced women forward, they also shifted backward to their former, pre-Neolithic status as a potent creative and legislative force.

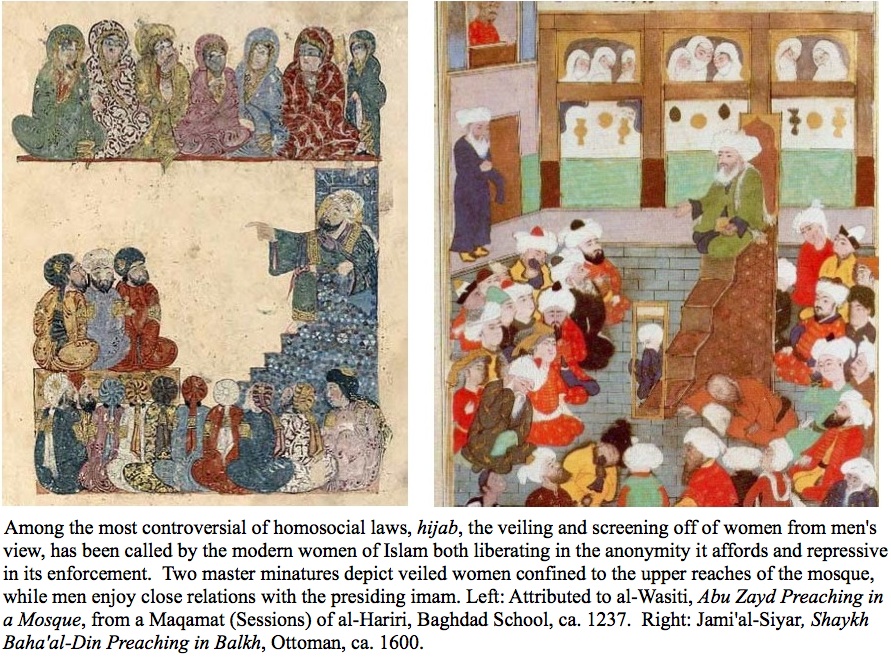

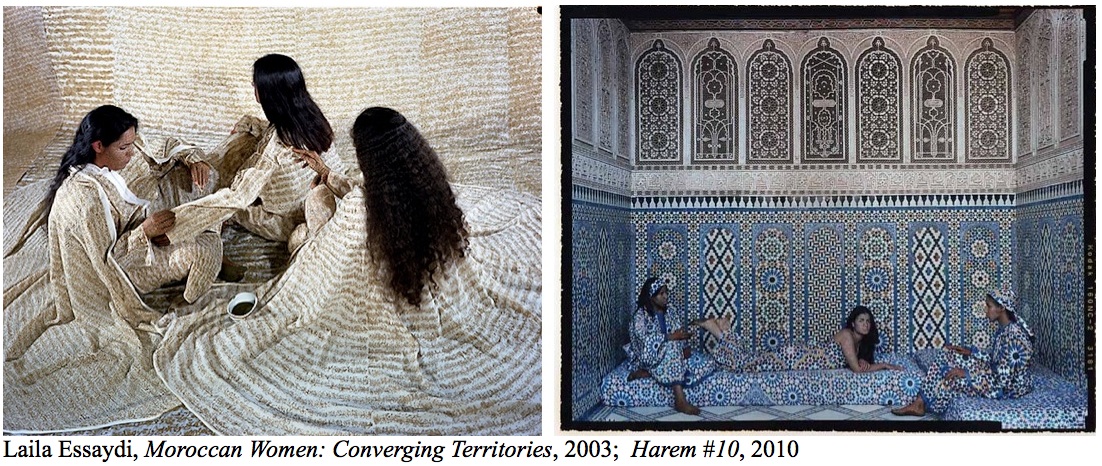

This propulsion back in time is especially irresistible because it is history that bears traction with the evidence of objects and significations, particularly the objects and significations of art. We find such allure in the photographs of Shirin Neshat, who is from Iran, and Laila Essaydi, who hails from Morocco and Saudia Arabia. Taken together, the two women exemplify a rare passage through historic homosocial barriers, in both cases the chadors and screens of hijab that keep fundamentalist Muslim women and men apart at the same time that they keep steeply Islamic societies from being understood by the modern, secular world. While Neshat's art exhibits many of the same codes governing homosocial dress and behavior depicted in the centuries-old Islamic miniatures of women's eyes peering out from recessed lambrequins and tightly-wrapped veils, Essaydi depicts Islamic women as they were imagined by the European Orientalists of the 19th century relaxing in the privacy of elaborate harem quarters. In either case, the two women convey how deeply runs the historical imprint of the Islamic homosociety of women. Seen together, it is almost too easy to conclude that women's captivity remains captivity in the trade-off between the fundamentalist Muslim and the Western colonialist keen on women's exploitation. And yet it is through the photographic and narrative access that Neshat and Essaydi supply that we gain sight of the hidden power that can emanate from Muslim women who band together to contend with male imperatives buttressed by the formidable writ of law. It is through such work that we begin to realize that what appears to be a divide of civilizations rasped out by religious difference is more deeply a variation in the degrees to which two different cultures enforce the male legislation of gender and sexuality. (For more on the discussion of hijab and the homosocieties of the women of Islam, see my work on Shirin Neshat at this link.)

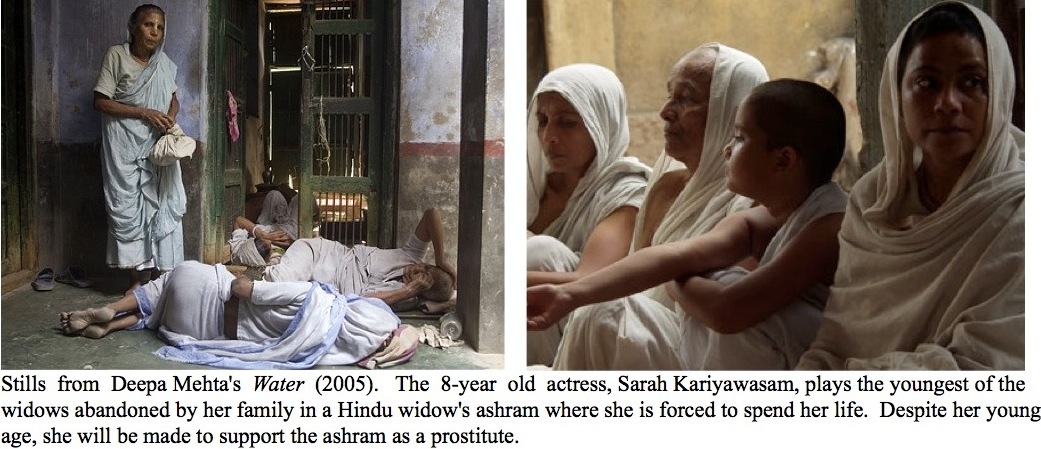

Deepa Mehta's films also peer into pre-modern women's enclaves with an eye on the ways and means that religious constraints--in this case Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Parsee restraints--have historically reinforced women's strength and resilience despite their enforced abjection--characteristics that men rarely emphasize in their depictions and accounts of women's homosocieties. But rather than focus on the collective strengths of women, Mehta brings the diversity of Indian women's response to male-imposed constraints to light. In fact, it is the opposition between the complicity and resilience of women faced with these constraints that affords the subject of Mehta's Academy-award nominated film Water (2005).

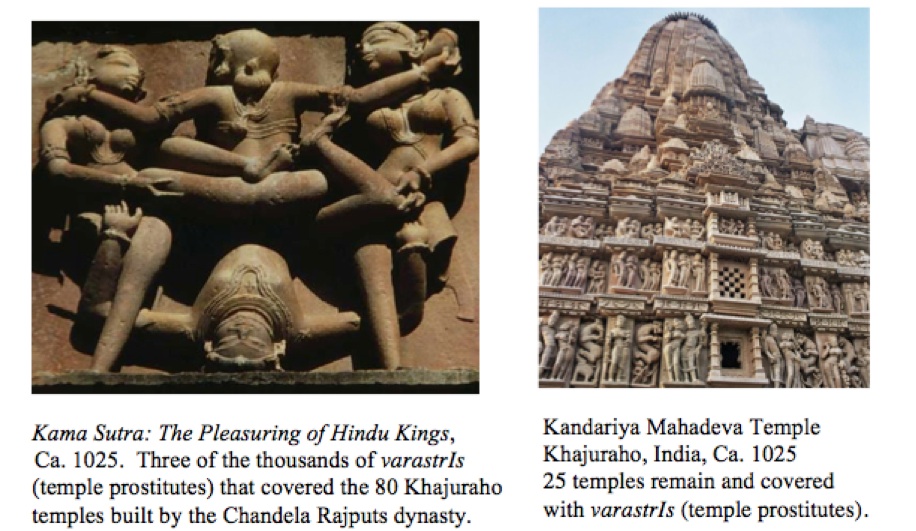

Mehta in fact takes on three male homosocial religious customs enforced upon women in India even today: the arranged marriages of child brides to mature and elderly men; the forced isolation of widows upon their husbands' deaths into widow ashrams where they live out their lives making amends for sins believed to have killed their husbands; and the forced prostitution of the most attractive and youngest widows--some of them children--to support the ashram. With a cast of actresses whose ages span eight to eighty, Mehta has filmed the plight of tens of thousands of India's Hindu widows who are confined to holy cities such as Vrindavan. With their heads shaved as required, they are forbidden reassimilation into society. Living as virtual untouchables, many on the streets, they live only to serve other women and to die. Although the ancient homosocial customs of Hinduism bares the brunt of Mehta's indictment, Water ultimately identifies the economic motive underlying religious homosocial customs--in this case the financial burden a widow poses to the deceased groom's family.

Because the films of Deepa Mehta treat sex and gender values significantly more ancient than we in the modern, secular West are accustomed to broaching in contemporary art--yet values which are still operative in Indian society and thereby starkly in conflict with modern attitudes--the homosocial order of women depicted is instructive of homosocial orders in general. It almost seems a maxim that we recognize the faults of others more immediately than our own; so the artists here discussed have come to count among the most prominent international artists to import indigenous variations on female homosocial orders globally.

In contrast to Mehta's, Essaydi's, and Neshat's depictions of religious women's homosocieties, Marina Abramovic's excursions into the homosocial divide consists of reprising mythopoetic imagery and ritual performance that represent the equalizing valuations of women believed to have marked many agrarian populations around the world. In Balkan Erotic Epic (2006), a multi-channel video installation, Abramovic dramatically extrapolates gender difference in separate but complementary erotic nature rituals. On one screen, a dozen or so female actors in traditional dress caress their exposed breasts and bare their genitals, then run with intent abandon amid rain-drenched, grassy fields to catch the falling semen of their fertility god. In a separate projection alongside them, an assembly of male actors is seen mock-copulating with Mother Earth.

The rituals seem absurd to us and at first appear to be pornographic parodies. But if we miss the meaning of Abramovic's reprisal of ancient homosocial rituals--if we find the rituals absurd, obscene, even comic--it is because the rituals have not survived Christianity, Islam, Marxism, and modernity as anything more than myths or parodies of their former, forceful belief systems. To put the rituals in their proper context for the viewer, Abramovic appears in one of the video channels delivering an anthropological lecture describing how the ancient Balkan societies thought that erotic energy was an indestructible force that came from the gods and was to be used reverently by men and by women to heal, protect, nurture, and ward off harm. In such societies the modern pornographic, commercial, and cynical significations of gender and sexuality is unknown. In contrast to the ancient and organic ritual societies, Abramovic suggests our own modern civilization and its displacement from reverent organic rituals heightens the disassociation between male and female sexuality while deadening our reception to the beauty and heroism that sexuality can bestow, both psychologically and politically.

Ultimately Abramovic holds that such disassociation of the modern individual from her own natural eroticism, and the disassociation of the male and female homosocieties from each other can have disastrous consequences. In fact, the staging of the erotic rituals was conceived by Abramovic as a deeply personal catharsis in the wake of the massacres perpetrated in the 1990s throughout Abramovic's homeland, the former Yugoslavia, in which the Serb, Croat, Montenegrin, and Muslim populations showed a sexual disconnection so complete that it led to men being taken from their homes and executed in groups just so that their women could be raped and sadistically tortured. Such crimes Abramovic believes can be traced back to a homosociality of men that promotes the pornographic degradation of women--which is why Abramovic films imagery that at first appears pornographic but which upon study can be seen to affirm the natural power of women's sexuality despite also retaining its homosocial character of binding women in social units securing their unity and strength.

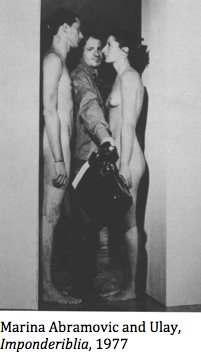

As her sense of the homosocial history of the Balkan peoples heightened, Abramovic was impelled to make, what was for her, a new kind of art--an art in which the differentiation of sex and gender shows itself to both generate, and be generated by, deep-seated mytho-spiritual belief and ritual systems. It marks a dramatically iconographic turn for an artist whose early work in the 1970s and 1980s, with her former partner Ulay, rendered the human body as a formal, conceptual, and contextual medium that reduces the role of gender to near irrelevance.

It may seem ironic that a man and a woman together, especially a pair who had famously been lovers, could work together to make gender irrelevant for the duration of their performances. It is more ironic still that we can today look back at the art of Marina Abramovic and Ulay as a model of the kind of asexual valuation and identification it takes to displace non-essential gender differentiation in a larger cultural context. In Light/Dark (1977), for instance, after Ulay slaps Marina on the face, Marina slaps Uay with equal force. In Relation in Time (1977), the pair entwined their equally long hair in an act that made facing away from one another compulsory, thereby thwarting sexual objectification in placing the object of desire out of view. Yet even in Imponderabilia (1977)--a performance in which the pair face off in the nude to constrict the passage of viewers so to force them to brush against the artists' breasts, thighs, and genitals--the pair reveal the exposed male and female bodies to be equally intimidating. In both physiological and emotional terms, Marina and Ulay came closest to reducing the homosocial divide to insignificance as any artist might conceivably come.

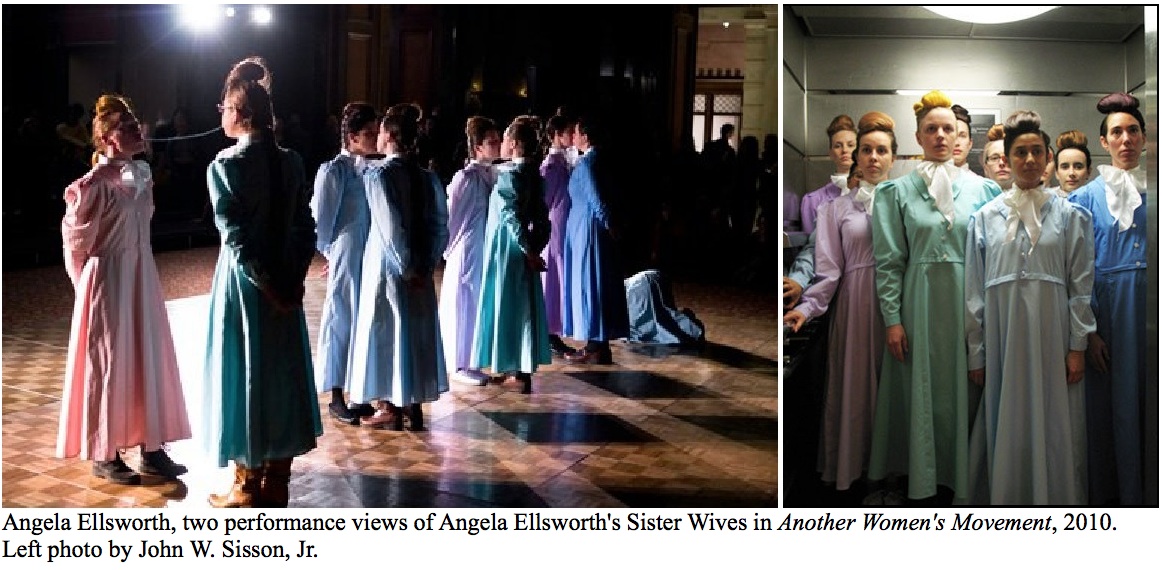

American women artists have largely focused on the forward thrust of expanding women's signification and codification in art rather than looking back at historic women's homosocialization. Angela Ellsworth breaks this mold of American feminism by signifying a uniquely American women's homosociety that is simultaneously historical and contemporary--the sister-wives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, the Mormon faith that originally embraced polygamy and encultured Ellsorth's ancestors. Ellsworth has internationally staged improvisational sister-wife performances with a troupe of actresses wearing the 19th-century prairie dresses and hairstyles of frontier women that still inform the modest dresses and hair favored by some of today's sister-wives. The performers enter and transit through gatherings at art galleries and museums, or outdoors before an audience. Such mingling itself is something sister-wives are disinclined to do, but the performers proceed to behave provocatively, indignifying their characters. The actions are defiant and activist parodies, not always verifiably indicative of real polygamy, sometimes imagined, yet realistically suggesting deeper, at times lesbian and incestuous bonds cohering the homosociety of sister-wives. We're made to feel that in staging parodies, the performances exorcize the legacy of Ellsworth's forebears from her own life, and thereby enabling the artist to chart out a little-understood enclave carved out by the larger homosocial codes constraining her family for generations.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.