Like millions of other Americans earlier this year, I found myself riveted by HBO's six-part documentary series, The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst. Part way through the penultimate episode, in which the notorious "cadaver letter" is introduced along with another, previously unknown letter written by Durst to his confidante Susan Berman (who authorities in Los Angeles now believe he killed), the story took an unexpected turn, to the far reaches of Humboldt County in the northwest corner of the Golden State.

As a fourth-generation Northern California, one who has spent a considerable amount of his life in Humboldt County dating back more than a half-century, I immediately recognized the background images that served as b-roll in this section: the stunning coastline off the coast of the remote village of Trinidad; the picturesque village itself (population 300); the small town of Garberville, 90 miles down the Highway 101 corridor. What, I wondered, was the eccentric, perhaps murderous, scion of a Manhattan real estate empire doing there?

That question went unanswered in The Jinx, save for a few vague glimpses of the glorious landscape. But Durst's lost years in Northern California play a crucial role in the capital case being brought against Durst by the Los Angeles County District's Office. Law enforcement officials believe that on either December 19 or 20 of 2000, Durst drove from Humboldt County down to Beverly Hills, where he killed Berman in her rundown bungalow a few days later. He flew out of San Francisco International Airport on the evening of December 23.

When asked in The Jinx about the choreography of such a five-day journey, Durst went into a long, circuitous exculpation. "The timing on all this gets very, very tight," he declared. "Because it's a long way from Trinidad to Los Angeles. I would have had to have gone from Trinidad to Los Angeles, I don't know when -- 19th, 20th, 21st, whatever [mumbles]. And then gone back from Los Angeles to Trinidad. And then gone to San Francisco and flown to New York. Not much time to do all of that. And the L.A. police have been investigating for a while now and they are unable to put [me] in Los Angeles."

"But they were able to put you in California," The Jinx's director Andrew Jarecki interjected.

"California is a big state," Durst responded in that distinctive New York cadence of his, a self-satisfied smirk appearing on his face.

I knew right away that it appeared Durst was lying. Jarecki, however, didn't challenge him on the logistics. There was plenty of time.

Durst was a master at spinning false narratives. He had, by his own admission, spun them around the disappearance of his first wife, Kathie McCormack Durst, in the winter of 1982 -- and, many believe, got away with murder. Those close to Durst -- family, friends, you name them -- have described him as an inveterate liar, "incapable of telling the truth," in the words of his brother Douglas.

Durst wouldn't have had to go back to Trinidad before leaving from San Francisco in December of 2000. All he would have had to do was drive to SFO, roughly a five-and-half hour commute north. California's not that big. It was seemingly yet another Durst lie, another subtle twisting of the narrative.

Durst seems to have spun an additional false narrative in The Jinx -- and Jarecki allowed it to go unchallenged as well. Durst claimed that he never wanted to serve as head of the family business, that he didn't care that his father had bypassed him in 1994 in favor of his younger brother Douglas. Those who know Robert Durst knew better. They say that he was livid about being bypassed by his younger sibling, angry and bitter, that he had blown up in the plush Manhattan offices of the Durst Organization. His friend, advertising executive Nathan Chavin, described Durst as "devastated" when he heard the news.

Within months of having been passed over for the throne, Durst escaped to the Emerald Triangle in Northern California -- a place where pot was plentiful and accessible, and where he could go essentially unrecognized -- to get away from his father and brother, to break away from the long arm of his family's influence. He had come to Trinidad to stew and to try to pull the varied pieces of his broken life back together. Maybe he had darker plans as well.

According to records in the Humboldt County Recorder's Office, Durst purchased a three-story ocean-view home in Trinidad from Diane Bueche, in June of 1995. "It was very rural," Durst would say in The Jinx about Trinidad. "Very pretty." Located on the corner of Van Wycke and Gallindo streets in the picturesque seaside village, Durst's residence -- with wall-to-wall decking and full-length picture windows on each level -- afforded sweeping views of the gorgeous Trinidad waterfront, arguably one of the most beautiful stretches of coastline in Northern California.

Bueche lived directly next door on Van Wycke, in a sprawling two-story shingled home with equally breathtaking views. The outgoing, well-off Bueche was "a bon-vivant" to her friends (many called her "Bo") who owned and managed several properties in Humboldt and Trinity counties. She quickly became Durst's friend, confidante and social guide to the North Coast. They went out to dinner, movies and cultural events.

More than likely, the Bueche-Durst relationship was platonic, though they kept in close contact with each other, even when one of them was out of town. Bueche would later say that they stayed in touch by phone, email, fax and letters.

In one letter Durst sent to Bueche (a copy of which was provided by Matt Birkbeck, author of A Deadly Secret: The Bizarre and Chilling Story of Robert Durst), he reportedly said that he had "so much fucking energy these days I feel like the top of my head is coming off." He cryptically mentioned rearranging the furniture in Bueche's bedroom and upgrading his burglar alarm. He asked rhetorically, "Do you know it is illegal to shoot your pistol in town even in self defense[?]"

In another handwritten note that Durst reportedly faxed to Bueche, he declared: "I'd love to joust with you, but you might crush me like a bug. However, if you enjoy crushing bugs, call me.... Maybe I'll get to bite you real good before I'm cornered."

Those who knew Durst in Trinidad recall an odd little man ("a weird, weird dude," said one; "a very strange guy" and "spooky," said another) who threw his money around with a small coterie of acquaintance, and who talked big but whose stories never quite added up.

Durst had told Bueche and others that he had a daughter (he did not) and that he was planning to develop property in rural Humboldt County, only to run afoul of the California Coastal Commission. There's no record of that. For a while he kept an office in Eureka's "Old Town," on E Street, though what he actually did there is anyone's guess. At one point he contended to be a botanist for the Pacific Lumber Company. At other times, he reportedly claimed to be an insurance investigator or a rare metals expert. He told a realtor that he had been a writer for the Wall Street Journal. None of it was true.

Durst was essentially a computer illiterate when he arrived in Humboldt, and apparently incapable of typing as well. He put up an advertisement for a computer tech at Humboldt State University's career center and eventually hired a student, Michael Glass, to work for him at his home in Trinidad. Like most who encountered Durst in Humboldt County, Glass described him as being an "odd duck" and "eccentric."

One memory for Glass stands out: Durst was thoroughly infatuated with Pixar's computer-animated blockbuster, Toy Story, which was released in 1995, right around the time Durst arrived in Humboldt. Durst wanted all the imagery on his computer -- including the screen saver -- related to Toy Story. Durst, Glass recalls, powerfully identified with the film.

One pattern of Durst's that was continued in Trinidad was that he hired a young, high-school aged girl to serve as his housekeeper (he had done the same in New York). While law enforcement profiles of Durst usually identify his interest in older women close to his age (a la Bueche), he always had a coterie of young women around him, too. Durst's housekeeper in Trinidad had a key to his house so she could come by when Durst wasn't there to clean up after him; he reportedly had a habit of throwing candy to the floor if he didn't like its taste.

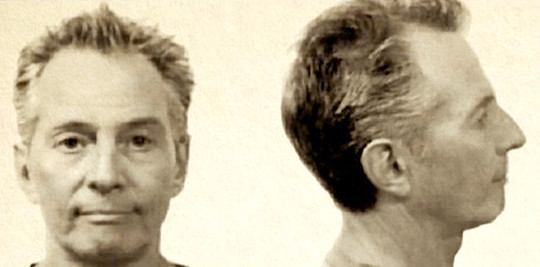

After the arrest of Durst in New Orleans this past March and the conclusion of The Jinx, I was looking through a newspaper search engine when I made a surprising discovery in the Ukiah Daily Journal from May 11, 1995, indicating that Durst had been arrested in Mendocino County for driving under the influence and possession of marijuana. Somehow this arrest had escaped everyone -- journalists and law enforcement officials alike.

The 1995 arrest was classic Durst. Pulled over in the tourist haven of Mendocino village after drinking a bottle of wine at the upscale Beaujolais Restaurant, Durst was allegedly found with marijuana and $3,700 in cash in his trunk, and he failed a series of field sobriety tests. Then in typical Durst fashion, with phrasing familiar to anyone who watched The Jinx, Durst uttered to a cop that "the money and marijuana is mine and I have always smoked it, even as a kid... So what's the big deal?"

After he left the Durst Organization in 1994, Durst had assumed an even more bizarre lifestyle than the one he maintained in New York. Durst had residences all over the country: in New York, Florida, Texas, Louisiana, and California, and several cities therein. He reportedly liked frequenting the tenderloin and skid row neighborhoods in various cities (including in Eureka), often hanging out with the homeless and the down-and-out.

In addition to his home in Trinidad, Durst also owned two upscale townhouses in San Francisco. "He never stayed in one place for more than a few days," says Cody Cazalas, the lanky mustachioed investigator from Galveston, Texas, who appeared in The Jinx. "He'd fly from Texas to California to Louisiana then back to Florida then Texas again," Cazalas told me. "He was extremely mobile. And very secretive about his movements. Two or three days was about it in any one place. He was all over the charts."

Robert Durst had become a very difficult guy to track down.

Little more than two years after Durst was arrested in Mendocino and had settled into his ocean-view digs in Trinidad, a 16-year-old high school student from Eureka -- Karen Marie Mitchell -- was declared missing after visiting her aunt's shoe store at the Bayshore Mall on the south side of town. The Mitchell case both captivated and galvanized the community. Over the next several years, numerous leads were exhausted, and several suspects were identified, though, ultimately, nothing came to fruition. It is a case that still haunts the community.

Although it's not clear when Durst first came onto the radar of Eureka investigators, according to newspaper records I tracked down, Mitchell's aunt and legal guardian, Annie Casper (with whom she was residing at the time of her disappearance), apparently first publicly identified Durst by name as a suspect in the Mitchell case in December of 2001 -- not 2003, as has often been claimed in the media. "[Durst's] been in our store twice, which I thought was kind of odd," Casper was quoted as saying in the Times-Herald. On at least one occasion when Durst was in Casper's store, according to a former store employee, he was dressed as a woman.

Shortly before Mitchell had gone missing in 1997, there had been another disappearance of a young woman in Northern California, Kristen Modaferri, an 18-year-old student from North Carolina visiting the Bay Area for the summer. One of the suspects in the Modaferri case fit a similar profile of Durst, particularly in respect to cross-dressing and prowling around homeless shelters. Oakland police investigators felt there might be a connection.

Although the Bay Area investigators didn't have sufficient evidence to pursue Durst in respect to Modaferri's disappearance, they felt that there was reason to pursue Durst further in respect to the disappearance of Karen Mitchell. According to Birkbeck's A Deadly Secret, the East Bay investigators believed that Durst was in Humboldt County on November 25, 1997, the day of Mitchell's disappearance.

One of the investigators, John Bradley, interviewed a woman then incarcerated in a San Francisco jail, Sheli C., who had lived in Humboldt County during the same period that Durst was living in Trinidad. A drug addict and a prostitute, Sheli had been arrested on narcotics charges. Bradley had a hunch that she might know something about the Mitchell disappearance. She didn't.

But when Bradley showed Sheli a picture of Durst, she reportedly recognized him immediately from Eureka, where, she said, Durst had frequented a homeless shelter only a couple of blocks from the office he kept in Old Town. "Karen Mitchell's aunt and guardian," Bradley declared in a report from 2003, "told me Mitchell volunteered at [a shelter in Old Town] for a brief period."

According to Sheli, Durst had tried to pay her for sex, but he always low-balled her, so, she claimed, it never happened. But when shown a second picture of Durst, she said, curiously, "that's what he looks like in the morning." She said that Durst's "pattern" was to hang around the shelter for a while, disappear for a couple of months, "then he would return to loitering around the homeless shelter."

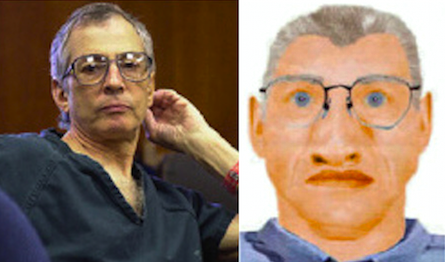

There had also been a composite sketch drawn of someone who may have been driving a car that Mitchell got into the day of her disappearance. A witness, Randell J. Gomes, had stepped forward months afterwards, and the sketch looked remarkably like Durst -- down to his oversized wire-rimmed glasses -- so much so that Bradley believed the informant had to have known Durst.

The last thing Sheli C. said to Bradley was that "weird people get tired of doing normal stuff." The line struck a chord with Bradley. Then Sheli went on the lam -- Gomes left town.

A frustrated Bradley and his partner never had a chance for any follow-up interviews.

On a cold and windy day in Eureka last month, I sat at the 5th Street Starbucks with Andy Mills, the city's recently-appointed police chief, who in the aftermath of Durst's arrest in March has quietly but surely reopened the Karen Mitchell case.

Mills, who arrived in Eureka highly touted from San Diego, was candid and forthcoming in his conversation with me. He described the Mitchell investigation as "reinvigorated and active," and said that while he was unable to identify any new evidence involving Durst, that Durst was very much in play as a suspect. "He's very much in the mix," Mills said. More recently he told me that that there was a renewed collaboration between the EPD and one of the Bay Area investigative units.

I've also learned that the FBI has presently assembled an unofficial nationwide task force specifically looking at a multitude of unsolved murders and disappearances wherever Durst has lived, stretching back more than 40 years. Indeed, there's a case involving a young girl who vanished after frequenting Durst's health food store in Vermont in 1971.

San Francisco investigator Bradley also believes that Durst has killed other victims. "I reasonably believe Durst was a serial killer," he wrote in an official report in 2004. "Others believe Durst only kills people he knows and with whom he has become enraged. I counter that his comfort level with killing is so secure, he kills strangers for practice then people directly connected to him and just does not worry about discovery."

Durst's defense attorneys, of course, have repeatedly denied his involvement in all of these murders. In a recent motion filed in New Orleans, his defense team has challenged the legality of the search warrant that led to his current incarceration and they have also contested the handwriting evidence linking him to the Berman killing in Los Angeles.

At the end of The Jinx, in which he reportedly provided the producers 25 hours of interviews, Durst stepped into a bathroom and apparently unknowingly uttered into a hot microphone what many have taken as a rambling confession: "There it is. You're caught. You're right, of course. But you can't imagine. Arrest him... What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course."

I asked Cody Cazalas in Galveston -- who believes with certainty that Durst killed his wife and Susan Berman, along with Morris Black -- if it would surprise him if Durst had killed more people. "No" he said with a long drawn-out pause. "No, no it wouldn't."

Maybe Robert Durst has been trying to tell us something all along. What if we were to take him at his word? Perhaps he's right and we can't imagine. Maybe, just maybe, he did kill them all.

Writer and filmmaker Geoffrey Dunn has won awards for investigative reporting from the National Newspaper Association and the California Newspaper Publishers Association. Longer versions of this piece appeared in the North Bay Bohemian, Good Times, and North Coast Journal.