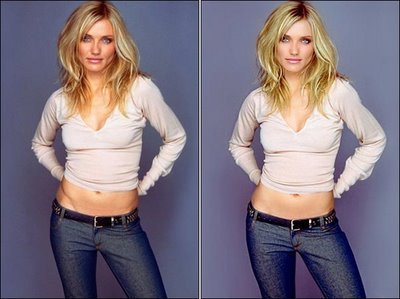

A former editor at Cosmopolitan, Leah Hardy, recently wrote an exposé about the practice of Photoshopping models to hide the health and aesthetic costs of extreme thinness. Below is an example featuring Cameron Diaz:

- Face: Cheeks appear filled out

- Bust: Levelled

- Thighs: Wider in the picture on the right

- Hip: The bony definition has been smoothed away

- Stomach: A fuller, more natural look

- Arms: A bit more bulk in the arms and shoulders

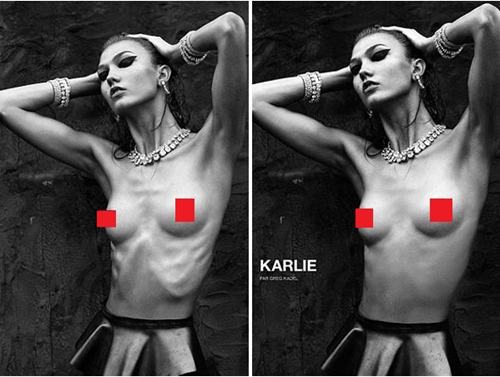

Hardy, the editor at Cosmo, explains that she frequently re-touched models who were "frighteningly thin." Others have reported similar practices. Jane Druker, the editor of Healthy magazine -- which is sold in health food stores -- admitted retouching a cover girl who pitched up at a shoot looking "really thin and unwell." The editor of the top-selling health and fitness magazine in the U.S., Self, has admitted: "We retouch to make the models look bigger and healthier."

And the editor of British Vogue, Alexandra Shulman, has quietly confessed to being appalled by some of the models on shoots for her own magazine, saying: "I have found myself saying to the photographers, 'Can you not make them look too thin?'"

Robin Derrick, creative director of Vogue, has admitted: "I spent the first ten years of my career making girls look thinner -- and the last ten making them look larger." Hardy described her position as a "dilemma" between offering healthy images and reproducing the mythology that extreme thinness is healthy:

At the time, when we pored over the raw images, creating the appearance of smooth flesh over protruding ribs, softening the look of collarbones that stuck out like coat hangers, adding curves to flat bottoms and cleavage to pigeon chests, we felt we were doing the right thing... We knew our readers would be repelled by these grotesquely skinny women, and we also felt they were bad role models and it would be irresponsible to show them as they really were.

But now, I wonder. Because for all our retouching, it was still clear to the reader that these women were very, very thin. But, hey, they still looked great!

They had 22-inch waists (those were never made bigger), but they also had breasts and great skin. They had teeny tiny ankles and thin thighs, but they still had luscious hair and full cheeks.

Thanks to retouching, our readers... never saw the horrible, hungry downside of skinny. That these underweight girls didn't look glamorous in the flesh. Their skeletal bodies, dull, thinning hair, spots and dark circles under their eyes were magicked away by technology, leaving only the allure of coltish limbs and Bambi eyes.

Insightfully, Hardy describes this as a "vision of perfection that simply didn't exist" and concludes, "[n]o wonder women yearn to be super-thin when they never see how ugly [super-]thin can be."

It's bad to police people's bodies, no matter whether they're thin or fat. This is an important point (made well here) and while I agree that some of the language is harsh, that's not what's going on here. The vast majority of the models who need reverse Photoshopping aren't women who just happen to have that body type. They are part of an social institution that demands extreme thinness and they're working hard on their bodies to be able to deliver it. This isn't, then, about shaming naturally thin women, it's about (1) calling out an industry that requires women to be unhealthy and then hides the harmful consequences and (2) acknowledging that even people who are a part of that industry don't necessarily have the power to change it.

A version of this post originally appeared on Sociological Images and Business Insider.

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College and the principle writer for Sociological Images. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.