This is Part Two of the seven-part series, XX CHROMOSOCIAL: WOMEN ARTISTS CROSS THE HOMOSOCIAL DIVIDE. Part One and a list of future installments can be found on HUFFINGTON POST here.

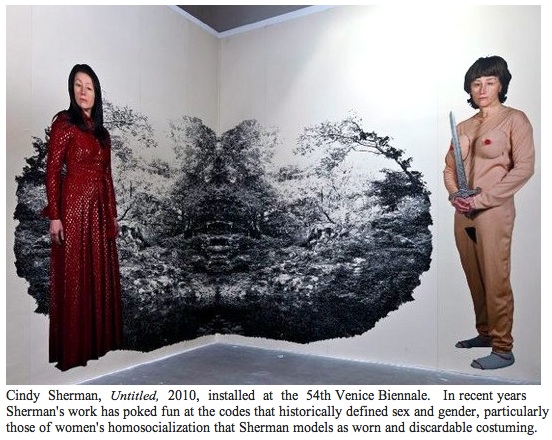

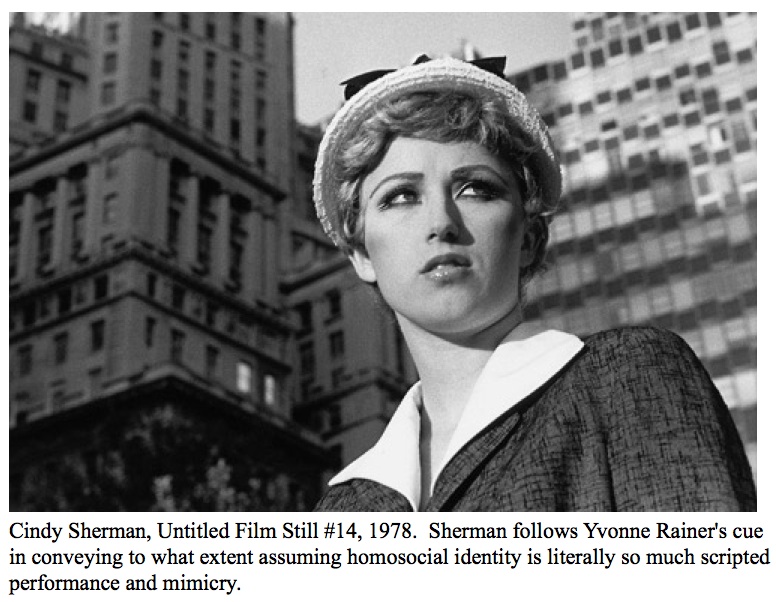

Gender and sexuality are becoming ever more mutable for the progressive and cosmopolitan global nomad--that small but growing breed of iconoclast, be s/he biologically male, female or in between. It's such individuals who are crossing and leveling the homosocial divide of gender and sexuality by assuming and casting off sexual personae as if they were playing at being Cindy Sherman. Of course it's a breed who make up but the smallest fraction of the human race. The vast majority of us conceive of ourselves as consistently and constitutionally male or female in following the same homosocial codes and espousing and perpetuating the same conventional sex and gender prescriptions and proscriptions that civilizations, societies and tribes have inherited for millennia.

How do we know this? By reading the art of history, and thereby the structures and codes of sexuality and gender--with all their attendant values and prejudice--conveyed by its signage. Historical art is where we go to find and decipher the means and customs through which homosocialization evolved from prehistory to the present while carving out the ubiquitous divide of gender constraining us explicitly and unconsciously. (See Part 1.) I say unconsciously because the human race didn't possess a concept or term for the "homosocial" regimentation of gender and sexuality until the late-twentieth century, which means we hardly understood why gender became so polarized and the sexes so segregated. In retrospect, it appears we required a developed and reflexive feminist, gay and transgendered global vision to see through the prejudice governing sexuality, gender, ethnicity and the legislative restraints that paternally impose on enculturation and self-identification. But we also required a historically global overview of art portraying human sexuality and legislative power to see the overarching patterns of human socialization.

From the mid-twentieth century on, our knowledge of world civilizations and societies coalesced to provide an unprecedented overview of the sexual and familial relations of power because that is when we also began valuing the world's art in all its forms with equal ethno-cultural valuation. With our newly heightened awareness of sexuality and art liberated from superstition, ethnocentrism, and unilateral male governance, we could begin to see that historical art for millennia portrayed the extent to which men gravitated homosocially to men and women to women for comfort in friendship and politics. This was something humans long understood, but we always presumed the division of labor and power along gender lines, and with the proscriptions that outlawed sexual and gender diversity for the better part of history, were issued to secure and perpetuate procreation and family.

With our new historical and global overview, we can see the full implications of the homosocial patterns that artists recorded from the paleolithic to the modern. But it wasn't until the mid 1980s, when such terms as the "homosocial" and "fluid genders" began to circulate, that we became possessed with a deeper understanding of why human socialization existed as one gaping divide. It was then that literary scholar Eve Kosofsky-Sedgwick theorized that male homosocieties and female homosocieties are separately bonded by a presumed non-sexual yet same-sex attraction that is no less compelling than sexual desire. Suddenly we possessed the language and visual model of a cement that we came to picture as the invisible force in our forefront: a cement enabling us to form compulsory expectation, comfort and empowerment that men could achieve by socializing primarily, if not exclusively, with men and women with women, and that manifested whether or not the family was made central to socialization.

It shouldn't surprise us that before Sedgwick published her theory of the homosocial bond, key women artists already were possessed of an understanding of the human homosocial proclivity. And why wouldn't they be, considering that artists had for millennia conveyed that sexuality and power were entwined, and that feminist artists in particular left no code unturned as they visualized (which means they took apart and reassembled) the signage of sexuality and gender intersecting with the signage of power.

To my mind, the first art to show glimmers of a reflexive understanding of the codes prescribing homosocialization and proscribing certain crossings of the homosocial divide manifested as an art critical of the codes that impel men and women to follow different scripts of behavior, including those unnatural to their personal orientation. Different commentators may trace the first significant glimmers of homosocial art to various artists. For my part, it's an art that is semiotically analytical or mimetic of the codes of sexuality and gender that yields the most enduring and deeply penetrating articulation of homosocialization, while specifying the codes confining late-twentieth century homosocieties. And among that artistic activity and analysis, four women stand out.

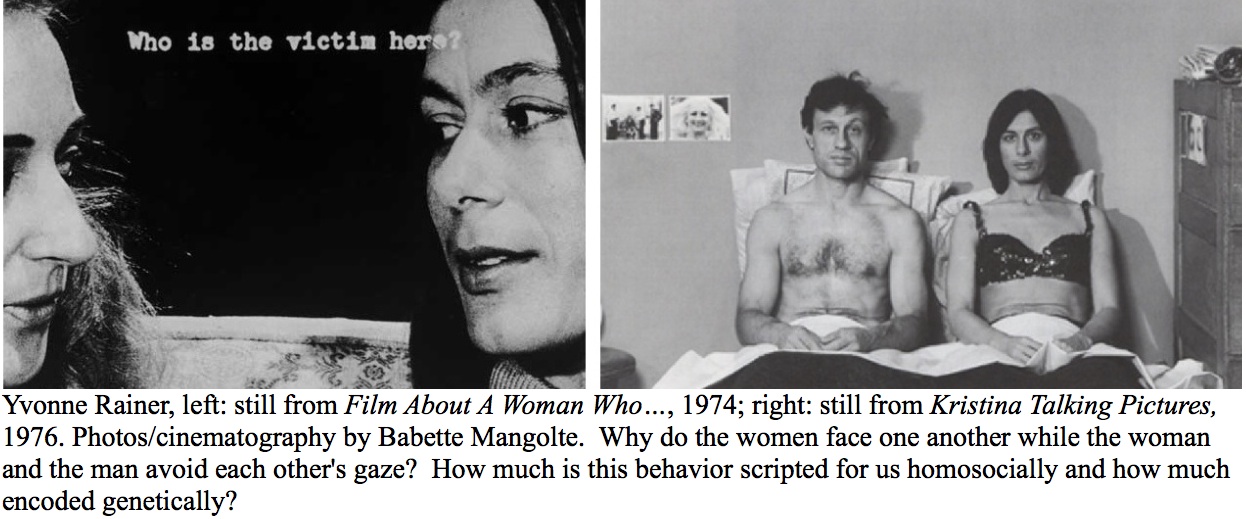

The art in which I first see a homosocial analysis lighting up is also an art that scrutinizes patriarchy and feminism in equal measure. The performances and films of Yvonne Rainer, beginning with Rainer's 1974 Film About A Woman Who..., (or perhaps her 1972 live performance, This Is the Story of a Woman Who..., which I did not see) shows itself to be a work as critical of unquestioning feminisms as it is of unquestioning patriarchy. This equal scrutiny is what is required for a homosocial study of society, and the passage from Film About A Woman Who... that I've come to settle on as the first truly reflexive homosocial introspection of note may account for why feminists, along with Rainer herself, were slow to proclaim the film feminist. What in 1974 seemed ambivalent, even cooly hostile toward feminism is in fact Rainer's usual rigorous and reflexive interrogation of any political intervention on individualism and artistry.

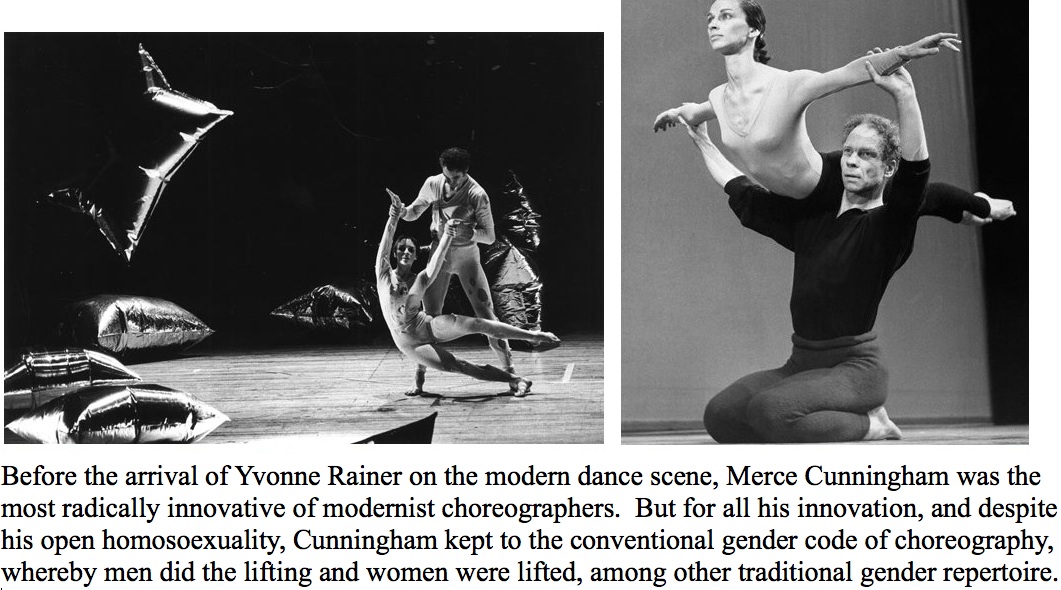

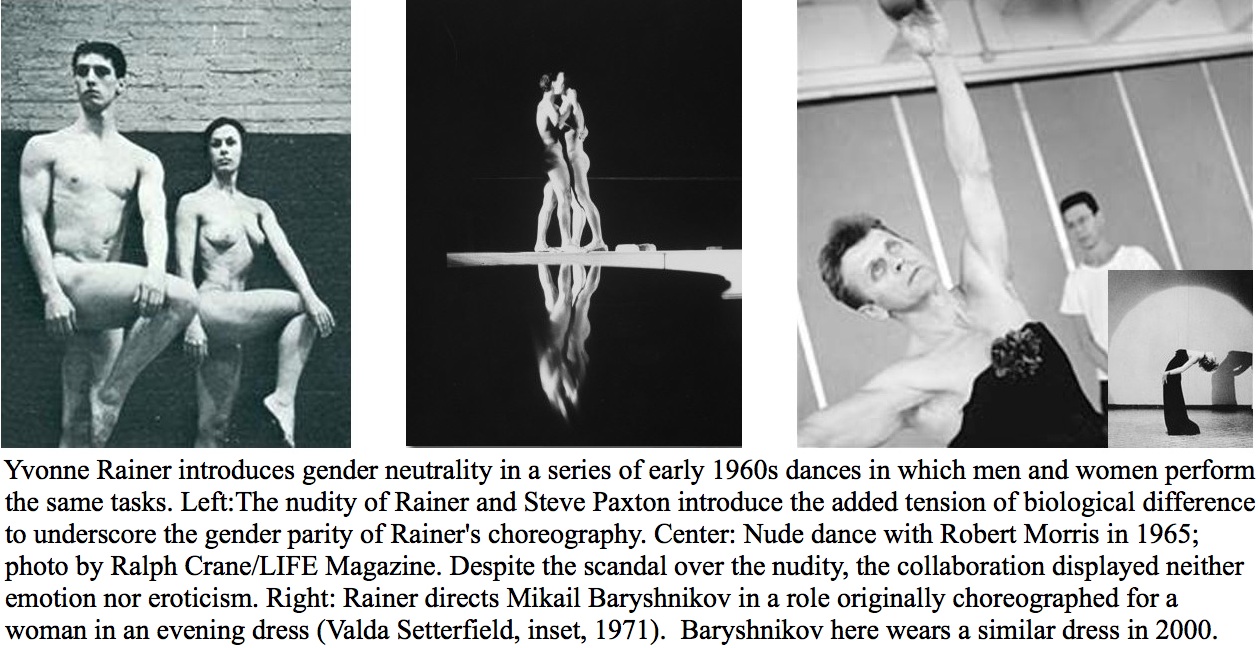

Rainer's query into the homosocial comes about unmistakably by her own individual participation in, and questioning of, the notion of "Woman." The very title, Film About A Woman Who..., with its coy ellipsis (...) begging that we fill in its blank while designating as suspect any term offered, implies Rainer was already treating "Woman" as a construct twenty years before gender theorist Judith Butler famously extrapolated her anti-essentialist critique of gender from Simone de Beauvoir. After introducing a decade of what might be the first choreography in modern history to display male and female dancers performing the same unisex movements--Rainer turned to film and narrative structures as a way of questioning and transgressing the kind of collectively-reinforced but unconscious identity formation that cinema perpetuates through the artifice of seduction. An excerpt from Rainer's screenplay makes her reflexive ambivalence toward gender roles apparent:

Closeup of S, Y, and R [three women seen sitting together on a sofa]. Pan back and forth across their faces. The Title "Who is the victim here?" appears at the top of the frame. The women are engaged in conversation, which is not heard.

[Rainer's] voiceover: "She finds herself looking at the other woman with curiosity. She has a way of talking--delicate, precise, and lilting--that reminds her of women she has had disdain for in the past. Effeminate women. Yes. Yet this woman's assertions emerge in spite of the style, and not unpleasantly. She is intrigued and self-conscious. The three of them talk about sexual fantasies. She keeps thinking about privacy. No, it isn't hard to talk about these things. It is almost too easy, almost meaningless, almost absurd. "What will I say to her when we meet for the second time?" she thinks. Then she realizes that the subject of conversation has come up because there are three of them. "An intimate revelation to her alone might demand a comparable gesture," she reasons. "With an audience of two my revelations are reduced to gratuitous display. I become a performer."

Beside supplying a Brechtian moment for drawing the audience's attention away from the narrative and onto the cinematic conventions historically used to define and codify the behaviors of women and men, Rainer is simultaneously analogizing the homosocial construction and constriction of the individual woman as so much performance--an actor playing out roles scripted for and handed down to her. What makes the film a gauge for both the homosocial underpinnings of the feminist agenda as well as the male expectation of sexual accommodation is Rainer's epiphany that, both in terms of patriarchy and feminism, she finds herself to be a performer. It's an inference of an undeniable homosocial tenor, whether emanating from the XY chromosome (male) side of the divide or the XX (female). For the homosocial identification is always a performance in that the actions performed aren't generated from the individual will and experience within, but supplied by a scripted scenario handed down to us.

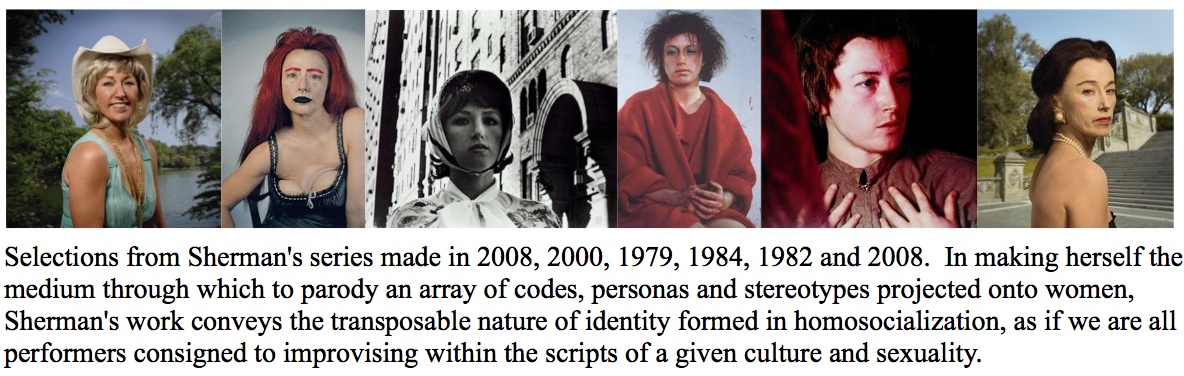

Within a few years of Rainer's early narrative performances and films, the floodgate for a visual semiotic of homosocial gender codes was further pried open. In Cindy Sherman's work, we find the female homosocial performance of an entire population of women parodied by a single avatar unfolding before our eyes the array of codes and scripts available to women through inheritance and unconscious social codification. Yet, to my mind, the single aspect of Sherman's work that provides the traction needed for a critical homosocial discourse to take hold is found in what is largely missing in her work--a significant representation of men. It was in the late 1970s that Sherman admitted to me that making herself over into a man has been more difficult and less successful artistically. Such a blind spot concerning male encoding is by itself announcement of a homosocializing barrier. It also indicates that Sherman's work is comprised almost entirely of women's cultural gender coding--codification she so richly exaggerates as to leave us feeling unresolved in our own valuation of the codes she heightens through both humorous and nostalgic parody and performance.

Illustrative of this is what I've heard expressed about Sherman's work over the years by feminists. In the most recent decade, Sherman's Film Stills have come to be celebrated for encapsulating a nostalgic glamour some women would like restored to feminist or lesbian culture. This varies remarkably from what I heard and read circa 1995 about the Film Stills--that they are ironic signifiers of women's alienation and male objectification--which is even more dissonant from what I remember expressed with the Film Stills' reception in and around 1979--that they embody the worst clichés about women, display an empty narcissism, and promote anti-feminist complicity with male desire. Yet despite this disparity of interpretations, which beside being generational and ideological reflect our evolving understanding of what women think and feel about women, everyone at least appears to agree that Sherman is telling us something about her life in relationship to women. My suggestion is that, as with Rainer's observation about the cultural construction of "Woman," the best of Sherman's "self-portraits" can be seen as summarizing what both pre-feminist valuations and stridently uncritical feminist valuations of women seem to us now: performances detached from the existential individual by a script of gender codes inherited from either the male or the feminist homosocial orders.

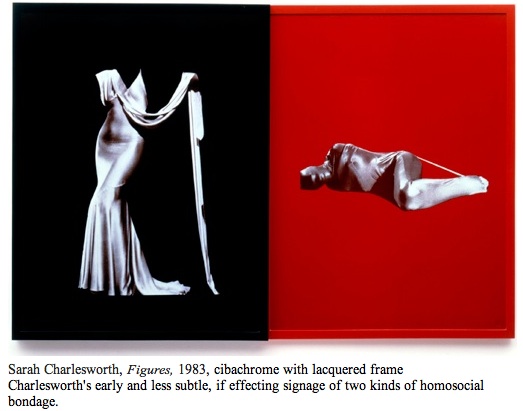

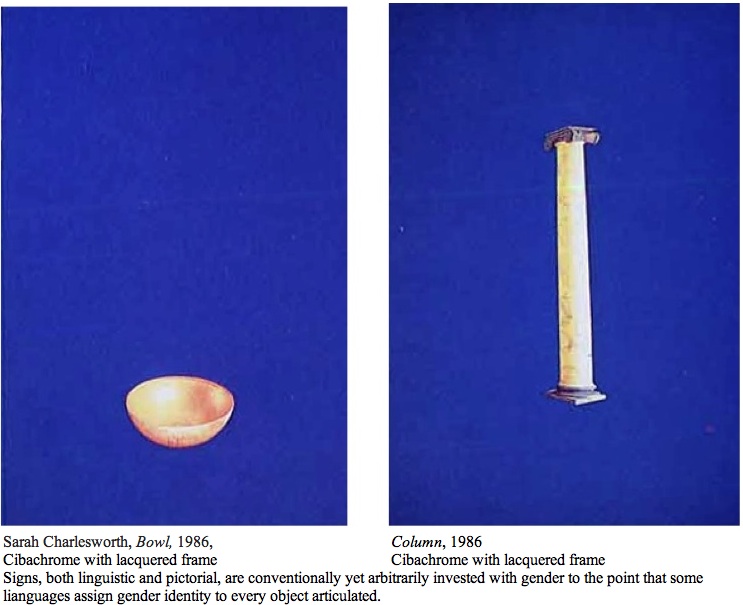

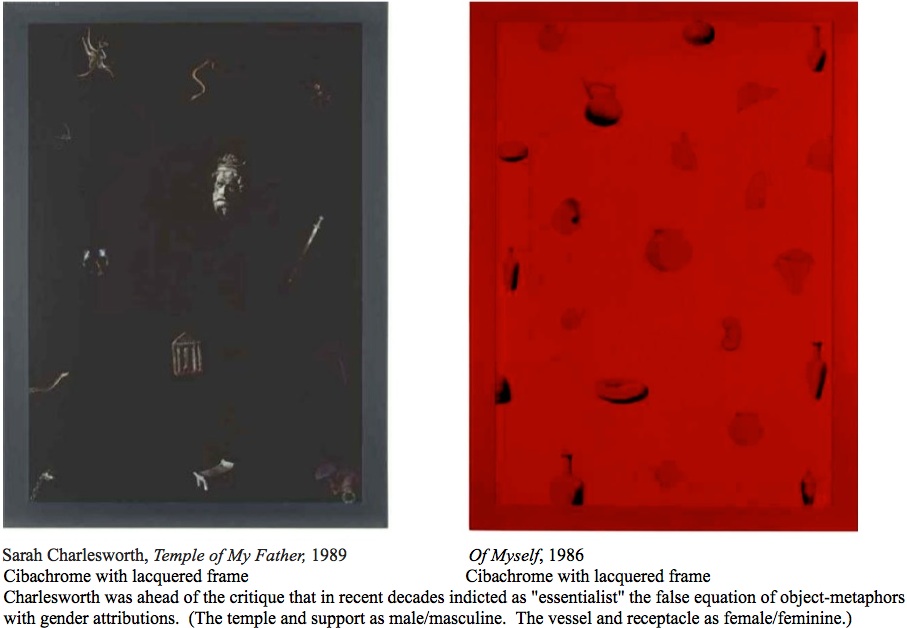

If Rainer and Sherman exemplify both the performative expectations of women's homosocieties and the homosocialized woman as a performer of homosocial scripts, Sarah Charlesworth and Lorna Simpson translate the linguistic codes unconsciously perpetuating male dominance into a visual iconography that makes us conscious and critical of the male sexual imagination that turns language into reality and law, even when it is unconsciously absorbed by feminist archetypes. Charlesworth's evocative visual isolation and recontextualization of pictorial metaphors, some in associative groups, draw attention to the homosocial features of engendered and engendering language, like features of the Romance languages of Europe which assign all nouns and modify every adjective with gender. Her depictions of so-called "male" and "female" archetypes (pillars and vessels) remind us that the world's living languages are so thoroughly stratified with the fossils of archaic homosocial structures that, even as the male homosocial imperative erodes in the global spread of modern gender parity, the world's textual, oral, and visual systems are generations away from being purged of such outworn gender clichés as "the pillar and support" standing in for men and "the vessels" signifying women--as was indicated by the "essentialist" values of pre-1990s feminism.

In this context, Charlesworth's art of semiotic and linguistic signification provides a rare model for the process of eradicating language of undesirable homosocial inheritance, a process she begins by first extracting and isolating the male homosocial object-metaphors from the world's ideologies, myths, cosmologies, histories, and arts. Once done, Charlesworth suspends the object-metaphors in evocative, monochromatic fields which, when substituted for historic and personal contexts by a process of association with the human body, make obvious the customary engendering of objects.

In the years during which Rainer, Sherman and Charlesworth crafted the prototypes for their life's work, a feminist and LGBT theory of media semiotics became exceedingly sophisticated. This was the period in which feminist, queer, and gender theory were radically redefined by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Judith Butler. While much has been made of Sedgwick's contribution to literary and political studies, scant attention has been given to the window her work opens onto the broad expanse of art history and contemporary artistic production in terms of art's open facility for organizing, codifying, and perpetuating the structures of homosocial power in given epochs and geopolitical locales. I'm referring specifically to Sedgwick's 1985 book, Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire, within which she articulates the homosocial attractions shared by people of the same gender to be the cement for the same-sex alliances that constrict power and privilege in all known societies.

Seven years later, Judith Butler's book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity challenged no less than the ancient-to-modern ontology of gender values we've inherited and demonstrated to be by no means immutable or universal, not even biologically necessary or corresponding, but no more than social constructs of an arbitrary if culturally and sexually functional origin. Since homosocial orders are entirely premised on notions of gender, taken in tandem, the two theories come at the biological essence of gender and sexuality from opposite ends--the collective (Sedgwick) and the individual (Butler)--with each overturning the once-tenable markers of gender, sexuality, and sexual politics along the way. It was a rare theoretical conjunction, a perfect fit, that puts the art of sex and gender activism of the 1970s and 1980s in much richer, detailed, and multifaceted relief than such art enjoyed at the time of it's making. Simply put, Sedgwick and Butler provided the language and variable and mutable gender, sexuality and desire that was missing in the discourse of art history yet proved to be most in sync with the invention of artists over the millennia.

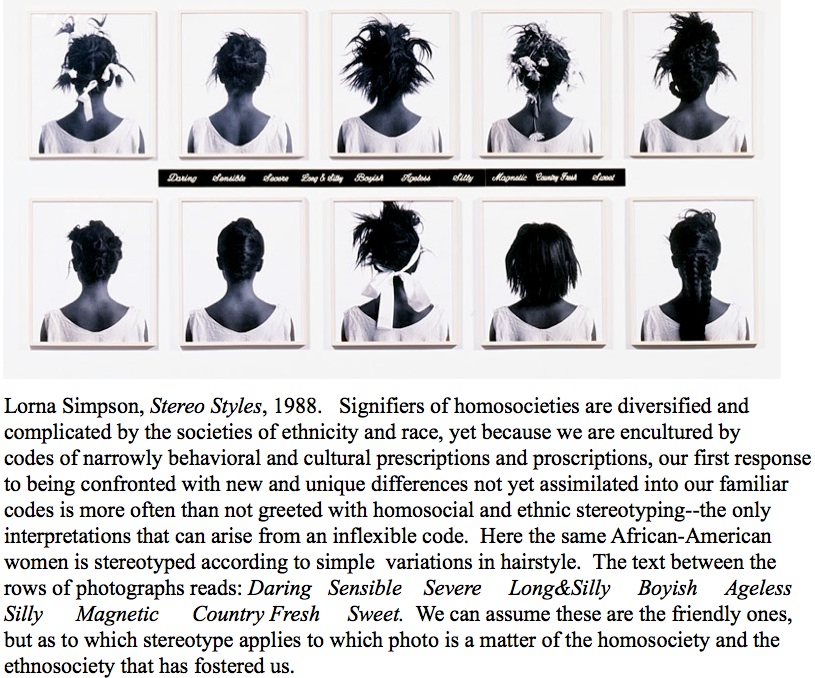

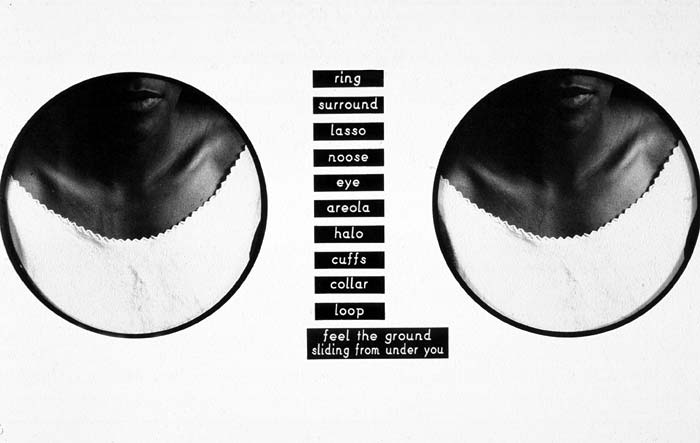

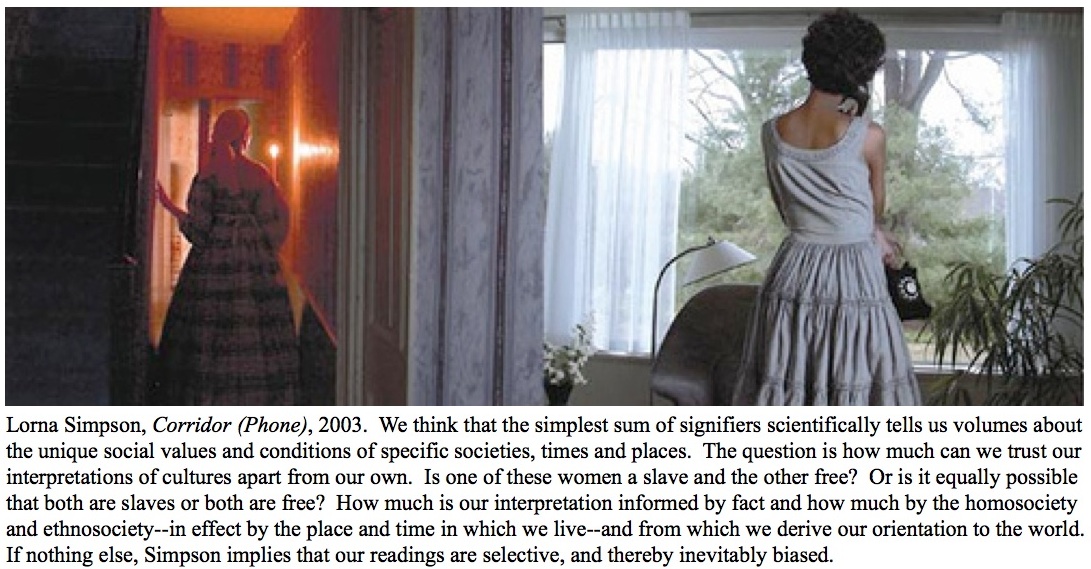

It was amid such acute visual and conceptual rearticulations of sex, gender, and homosocieties that Lorna Simpson introduced her art of linguistic, historical, and culturally-expansive critiques of enforced views of race, gender, and sexuality. Like Charlesworth, Simpson indicted language for imposing gender valuations where none need exist, at the same time that she scrutinized mainstream iconography that participated in the codification from which cultural stereotypes grow. Essential to Simpson's work is an understanding that errors in metonymy--a figure of speech in which one word or phrase is substituted for a another--and particularly unconscious synecdoche--a figure of speech in which a part is used for the whole. In our unconscious and everyday use of metonymy and synecdoche, we too often effect a confused conflation of metaphors with reality. It's a confusion that in its most willful usage accounts for, if not the direct formation of stereotypes leading to bigotry, certainly the illogical but presumed justification and reinforcement of stereotypes by the bigot.

Simpson's art was designed around a deliberate if discreet disjuncture between the images of the African American woman and the words used in various contexts to project culturally-prescribed stereotypes on her person, clothing, hair, postures, and gestures. Think of the way that words like "kinky," "nappy" and "funky" were made referential of women of African descent because such terms were used first to describe the women's hair and later were transferred to their sexuality by association. Simpson hereby traces the illogical use of homosocial metonymy and synecdoche, whereby parts are used to represent a whole class of people, as one root in the formation of a falsely assumed gender and racial uniformity and essence. As Simpson's work systematically dismantles the unconscious features of stereotype before our eyes, we find voids of reason left in the place of the uprooted prejudice. In other words, Simpson's imagery leaves us without a script to cue us in on how to "properly" (that is, conventionally and with prejudice and stereotypes) read, assimilate, and respond to the homosocial and racial codes we're presented. We are in effect compelled in our disorientation by Simpson to respond cognitively to the experience of the person we see represented before us without the "benefit" of our customary historical, racial and homosocial conditioning.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.