Zadie Smith has always been a gifted impressionist, sometimes to her detriment. In her debut novel White Teeth, the breadth of accents and dialects she conjured figured heavily in reviews crowning her the next big literary star. A random stab at a page produces an education in words and phrases not found in a dictionary. From page 155 of the Vintage International edition: "'sbit," "fuckwit," "'sall," "Mangy Pandy." From there, she’s gone on to write from the point of view of a half-Chinese, British-born, 27-year-old in The Autograph Man, as well as all highly individuated members of an American-English-Jamaican family, in her followup campus novel On Beauty. As impressive as this skill for pure transmission from ear to pen is, the result can be cacophonous on the page. It can also distract awestruck critics from giving Smith reason to nurture her considerable other gifts.

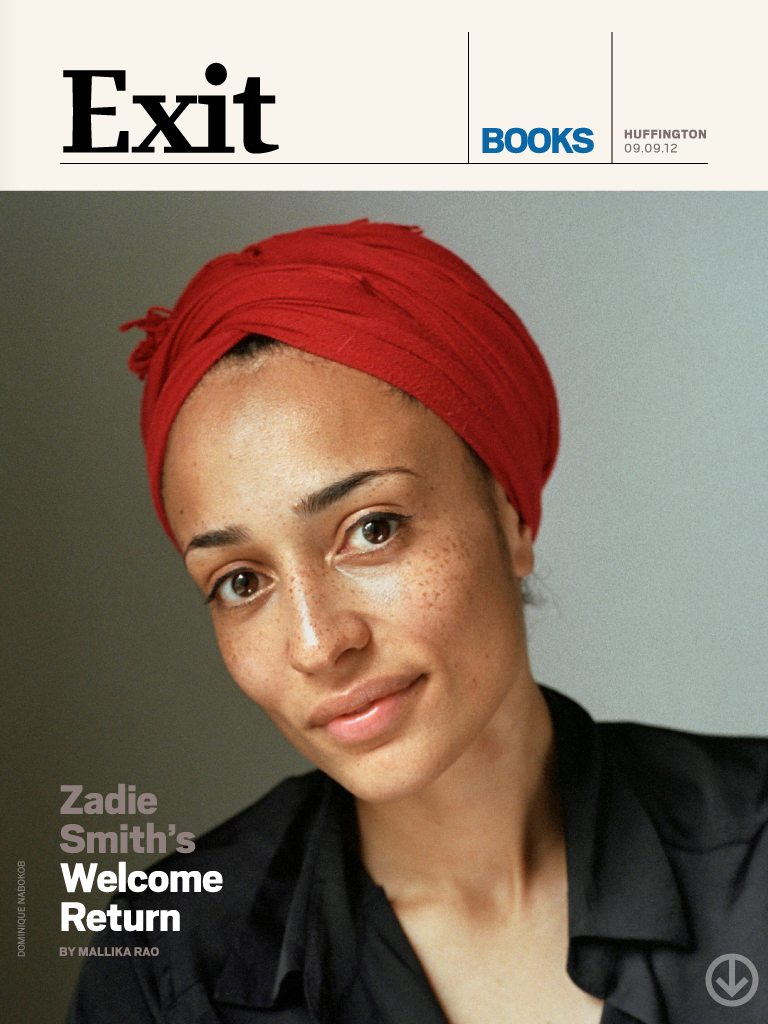

So Smith’s latest, fourth addition, NW — published this month, marking an end to her 7-year-hiatus from fiction and her entry into motherhood — is a welcome, evolved return. The shifting portrait of former residents of a housing project in London’s Northwest district shows Smith to be as enthralled by human biodiversity as ever, but cannier at using her insight sparingly, and to greater effect.

The novel’s three main protagonists, all in their mid-thirties, belong to the same generation as Smith herself. The band names, television shows and fashion statements of the time are all name-checked in characteristic Smith fashion. Here lies Friends; there vintage Kinks. Stylistically though, NW is new territory. The sentences tend to be short on their own, and imagistic en masse. Only six words of the first paragraph are spent describing Leah Hanwell, the novel’s earliest protagonist. “She keeps to the shade. Redheaded.” remains the bulk of what we know of Hanwell’s look: pale, red, Irish (later we learn she’s tall and thin). A chapter toward NW’s end is a line long. For Smith, whose quick, hyper-articulate sensibility can limit her to the title of comic novelist, this departure into what feels at times more like poetry than prose seems like a journey painstakingly mapped out.

But it’s great fun to follow. Many of the characters bear the names of Smith heroes past (Hanwell, Iqbal, Irie), and in some ways the novel feels like a greatest hits compilation playing out in an alternate universe. Once the action gets going, we’re off in a dreamy, layered land where dialogue functions as signals. Each time the words “bruv” and “blatantly” come out of the mouth of Felix Cooper, the cheery, reformed drug dealer whose POV makes up an interlude between sections on Hanwell and her oldest friend Keisha Blake, Smith is signaling, not riffing. Cooper’s fondness for standard nicknames (“bruv,” “blud”), and by extension, stylized intimacy, turns out to be his downfall. “Blatantly,” as well as “literally,” which punctuates a later section of the novel, act as markers on a shifting timeline. “That was the year people began saying ‘literally,’” Smith’s omniscient narrator explains.

This magic sustains until the novel’s end, when the wrap-it-up feel of an awards ceremony speech takes hold, and the varying plots’ loose ends are slicked together as if by necessity. Without giving away any surprises, the occurrence that finally links Hanwell, Blake and Cooper in a way presumably unique to their shared geography, feels contrived, inserted for reasons of “seriousness” rather than narrative propulsion. But then, the telling of the event is done with such agility, it’s hard to be bothered.

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.