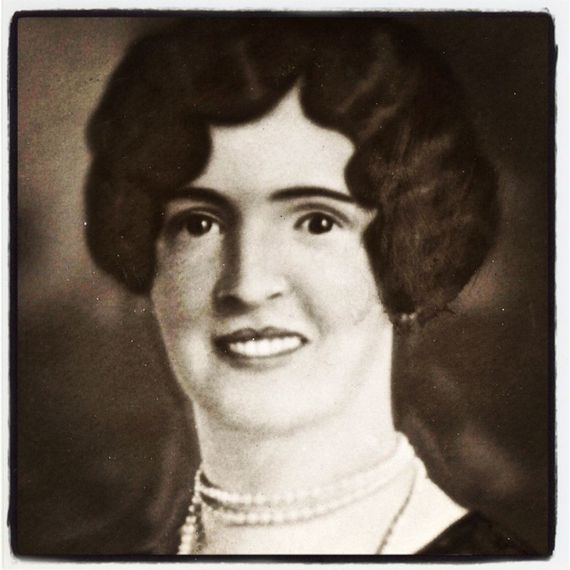

When she was 20 years old, she traveled from her home in Ballyjamesduff, County Cavan, Ireland, to Liverpool, England, where she purchased a second-class ticket and boarded The Baltic ocean liner.

Eleven days later, on Dec. 19, 1920, she arrived at New York's Ellis Island, alone, with $20 in her pocket.

Her given name was Ellen Brady and she went by "Nellie," but on his manifest, the immigration clerk recorded her first name as "Ellie."

She was my grandmother.

It was the date stamp that flashed across the screen as The Immigrant, the splendid new film from director James Gray, began that caused a catch in the back of my throat: "Ellis Island, New York. January 1921."

That was just a few weeks after my grandmother arrived at the busy immigration station in New York Harbor.

The coincidence brought tears to my eyes and dredged up an emotions I didn't realize I had throughout the rest of the nearly two-hour film.

[WARNING: some spoilers ahead.]

The Immigrant stars (and was written for) Marion Cotillard in the eponymous role as Ewa Cybulski, a young, single émigrée who sails with her sister Magda (Angela Sarafyan) to New York from their native Poland. When the sisters arrive at Ellis Island, Magda, who is suffering from some sort of respiratory ailment, is quarantined and separated from Ewa, who is, subsequently, threatened with deportation for being a woman of "low morals."

We suspect otherwise, but it isn't until much later in the film that we learn Ewa didn't sell her body on the journey to New York; rather she was raped by men on board the ship that spirited her to a new land of opportunity.

Immigration officials tell Ewa they've heard about what she had "done" on the ship as she sailed to the United States. They told her that the address of her relatives -- an aunt and uncle who had settled in Brooklyn -- didn't exist; that there was no one to greet her, she was unwanted, and would have to return to Poland.

Ewa is "rescued" by Bruno (played by the magnificent Joaquin Phoenix), a charming man who claims he represents an immigrants aid organization. Bruno manages (via an established bribe racket to funnel vulnerable women his way) to get Ewa off of Ellis and into Manhattan island, where he offers her a place to stay and work as a seamstress.

She is wary of Bruno and with good cause. Soon enough, with ample promises of helping her raise the money to release Magda from the hospital on Ellis Island, rather than sewing clothes Bruno casts Ewa in his racy vaudeville show (playing a relatively demure, fully clothed Statue of Liberty among a cast of topless "immigrants" from "exotic" lands), and, eventually, pressures her into prostitution.

Despite her wide, dark eyes and slight frame, Ewa is neither weak nor naive. She is, however, thanks to the men (and a few women) determined to exploit her from the moment she stepped onto the boat in Poland, desperate. Bruno and others prey on her desperation and she knows it.

But what choice does she have?

She is a young, unmarried woman; alone, poor, and "undocumented." She risks arrest and deportation if she seeks help from authorities, who may not be able (or willing) to offer any tangible assistance. Ewa chooses what she believes is the lesser evil, realizing that she has no "good" choice to make.

Enter Emil (Jeremy Renner), aka "Orlando the Magician" (and Bruno's cousin), who takes an immediate shine to Ewa, offering her a rose when he performs for inmates at Ellis Island while she is detained there.

Unlike the rest of the people she's met since her arrival in New York, Emil doesn't want her body. But he still wants something.

Both Bruno and Emil want Ewa, for different reasons, none of them entirely good. Their lust to possess the winsome émigrée sparks familial rivalry and tensions that end badly for all involved.

There is ample pathos, tragedy, and small victories in The Immigrant, but I'd stop short of calling it a "melodrama," as more than a few other critics have chosen to do. Director Gray, who says Ewa's story was inspired in part by old family photos taken by his grandfather who arrived at Ellis Island in 1923, demonstrates restraint in this stellar period piece and doesn't go for the easy extra squeeze of drama or emotion when so many others would.

The tale he tells struck a deeply truthful chord in me, even if my own grandmother's fate was somewhat less tragic than Ewa's.

When The Baltic pulled into port at Ellis Island in late December 1920, Nellie disembarked, made her way to the immigration inspector, answered his 29 questions, and walked into the Great Hall to find her older sister, Rose -- who had herself arrived at Ellis Island in 1913, married, and settled in New Jersey -- waiting for her.

She moved to New York City, where she had other siblings, and eventually settled in working-class Stamford, Connecticut. Nellie worked as a domestic for a wealthy family; and soon met, fell in love with, and married my grandfather, Francis Page, himself an orphan of immigrant parents from Ireland and England.

Poppy Page worked for the railroad -- in a job that had him outside in the fresh air he required after having been mustard-gassed during World War I -- and Nellie bore him four children.

My mother, Helen, was Nellie's middle child. And when my mother was three, my grandmother died during labor with her fourth child, a girl named Elizabeth, who passed away shortly after she was born.

Nellie's story is tragic, and she endured hardship as an immigrant. But not to the extent that Ewa did, and not in the way far too many immigrants still do today.

Ellis Island, which at the time of Ewa's and my grandmother's arrivals processed an estimated 5,000 immigrants each day, closed in 1954. The immigration process in the 21st century is much different from what it was in 1921. There are many more hoops to jump through as well as far more oversight with accompanying checks and balances. At least that's the plan.

My son is an immigrant. He arrived in the United States from his native Malawi 103 years after his great-grandfather from Italy; 105 years after his great-grandmother from Italy; and he became a citizen 90 years after his Irish great-grandmother, Nellie, first set foot on Ellis Island.

When we arrived as a family at Los Angeles International Airport, with our legally adopted son and an official dossier of supporting paperwork from the state department, we had to wait for hours with other immigrants from Asia, South America, eastern Europe, Africa, and the Middle East until we could let him our boy into the arms of his chosen uncle in the arrivals hall.Our clerical delay was a minor inconvenience and a tiny taste of the hardships Ewa and millions of other immigrants endured.

"When you see Uncle Dave, that's when you're officially a U.S. citizen," I told my son.

I'll never forget the leap he took and how David caught him mid-air, hugged him to his chest, and said, "Welcome home, buddy."

Safe. Secure. A citizen with all the rights with which I was born; the rights that immigrant grandparents came to this nation to secure for us.

In 2014, nearly a century after Ewa and Magda arrived on our shores, immigrants remain easy targets for corruption and exploitation, whether they are forced into prostitution or modern-day slavery, paid less than a living wage or less than their non-immigrant coworkers, or face more subtle intimidation and discrimination from employers, schools, landlords, neighbors, and even the government (local and federal).

The Immigrant stands as a reminder that, while we have come so far in this nation of immigrants, we have still farther to go to live up to the promise of Emma Lazarus' poem inscribed beneath the broken chains on the pedestal where Lady Liberty stands in New York Harbor:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"