In October, my first solo show of paintings, Blue Leah, opened at Dacia Gallery in Manhattan. The Huffington Post's Priscilla Frank was kind enough to review it here.

All of the paintings in the show depicted a single model, Leah, with whom I worked for several years.

One of Dacia Gallery's house policies is that the artist gives a talk about their work at the opening of their show.

Daniel Maidman, Blue Leah #2, 24"x36", oil on canvas, 2011

This is a slightly edited version of the talk I gave at the opening of Blue Leah:

"So -- this talk is supposed to be about why I paint, or what my paintings are about, or something like that. I'd like to tell you a favorite story of mine on this subject. It's from Pliny the Elder, and it's one of the Greek myths of the invention of drawing. In this myth, a young woman from Sicyon, near Corinth, is sitting with her boyfriend. He has to leave the next day, and she's going to miss him. They're sitting by the hearthfire, talking. Suddenly she turns and sees the shadow of his profile on the wall. So she grabs a piece of charcoal, and makes an outline of the shadow, to remember him by. And that's the invention of drawing.

Paralleling this myth is a medieval story about the crucifixion. Jesus is walking the Via Dolorosa, hauling the cross toward Golgotha. He's sweating, he's bleeding. He's covered in mud, people have been spitting on him. A woman in the crowd, a sympathizer, takes off her veil, and pats his face with it. When she takes it away -- a miracle! There is an image of his face imprinted on the veil. This image is the true image of the face of Jesus, and in the middle ages, they even had a fakey Latin-Greek term for this concept of the True Image: the vera eikona. With a bit of folk etymology, the name of the True Image, the vera eikona, becomes the name of the woman -- Veronica.

Both of these stories, the woman from Sicyon, and Veronica, are stories about the True Image. They are myths based on the importance to us, as human beings, of making a True Image. But they have something else interesting in common: the means of producing the True Image is essentially mechanical in each case.

So the question arises -- if the means of manufacturing the True Image is mechanical, why do we still feel a need to paint after the invention of the camera?

I think we can answer this question by drawing on a concept raised by Neal Stephenson in his recent novel Anathem. In this novel, the main character is press-ganged into serving as an amanuensis. 'Amanuensis' is a fancy word for a stenographer -- somebody who writes down what somebody else says. The main character, very reasonably, asks why they don't just get a tape recorder and some voice recognition software. And his boss explains to him that what is needed isn't a record of the words alone, but also that the words should pass through consciousness on their way to the record. It is absolutely essential -- for narrative reasons -- that a consciousness should parse the words.

This pertains to our question.

It is necessary that a consciousness parse what is seen for a True Image to be produced.

The finger on the shutter, the hand that holds the brush, the arm that swings the chisel -- these are extensions of consciousness. They are required to produce a True Image.

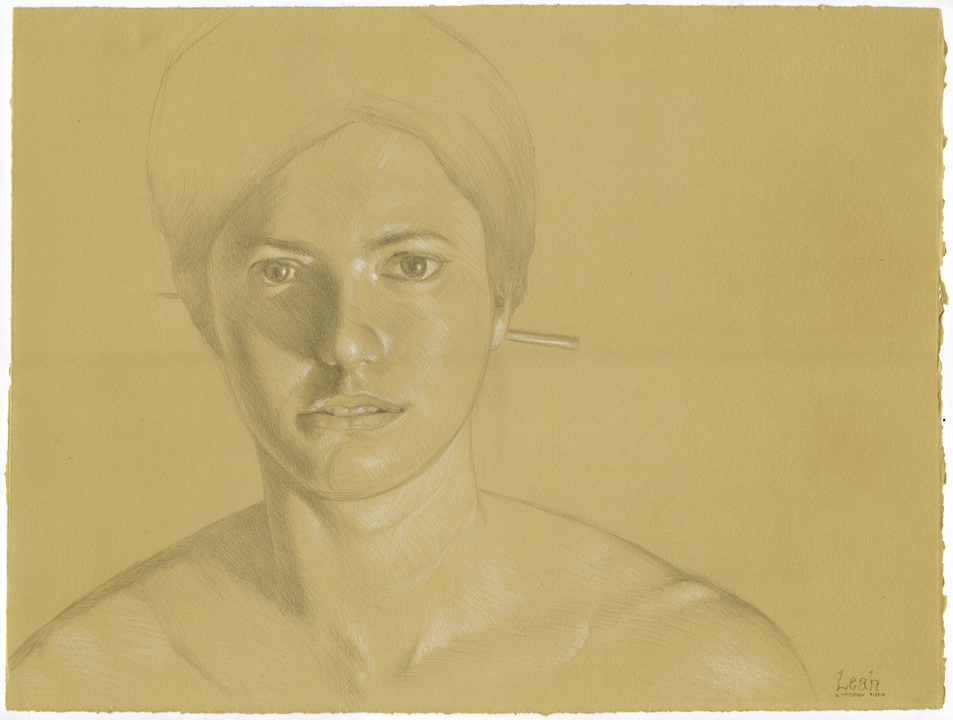

Daniel Maidman, Preparatory Sketch #1 for Blue Leah #3 (rejected lighting), 15"x22", pencil on paper, 2011

Why? To answer this, we have to answer: what is the True Image a true image of? It is entirely possible to measure the density or volume or boiling point of iron, for example, by mechanical means, or to find out the color of a star. These are purely physical phenomena. Machines are good at representing physical things. But it is next to impossible for a scale, a telescope, a surveillance camera, to represent consciousness, or the soul, the spirit -- whatever you want to call it. The True Image is an image of something that is not physical. It is of the same nature as consciousness, and this is why consciousness must parse it to represent it accurately.

When we paint, we are making an image of a spiritual phenomenon. The image itself begins to partake of consciousness, owning itself and making person-like demands on the viewer. It is very difficult to make such an image. It is not hard for the artist alone. It is also hard for the model. Modeling as a practice is physically demanding. It is a form of athletic activity. And more than that, the model must present themselves, make who they are available. Their consciousness must, unhidden, interact with yours. It is very difficult to do, and I am very grateful for having worked with my model -- can we all give a hand to Leah, who is here tonight?

[applause, Leah blushes]

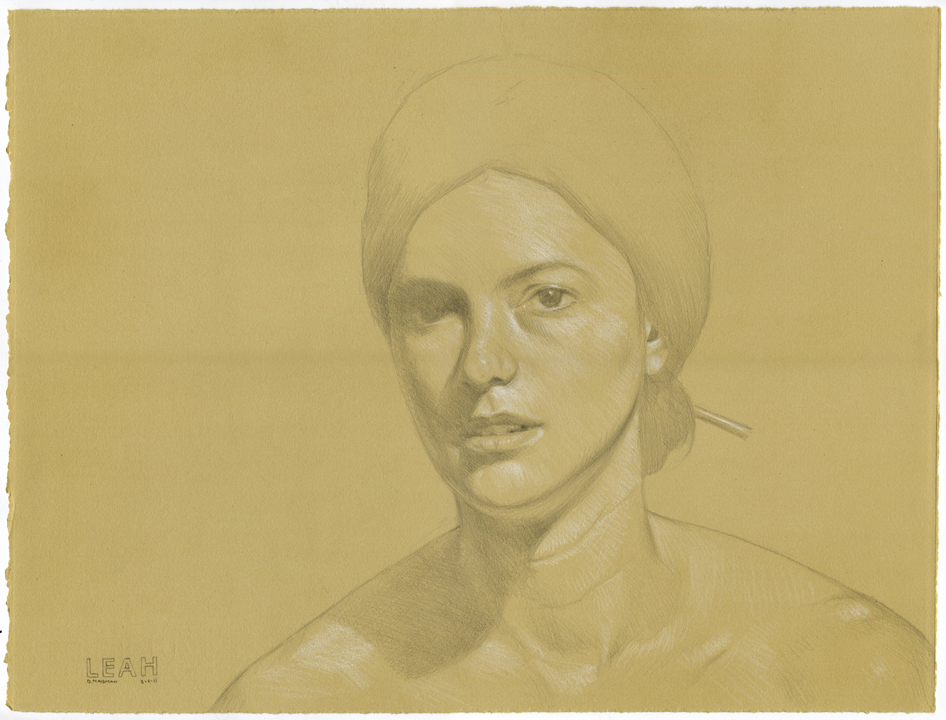

Daniel Maidman, Preparatory Sketch #2 for Blue Leah #3, 15"x22", pencil on paper, 2011

Now, given how difficult it is, let's ask again: why would anyone bother? Why is the True Image so important to us? I think Plato addresses this problem with his distinction between Being and Becoming. Everything eternal -- ideas, mathematics, things like that -- is described as partaking of Being. Everything that changes, that comes to be and passes away, that lives and dies, is described as partaking of Becoming. And Plato says that that which is Becoming is an illusion. It doesn't really exist. Why does he say that? Because he is human, and he is subject to that anguish we all feel in the face of the terrible vanishing of everything we love, that is death. His position is a radical rejectionism. He rejects death. He says, "It is impossible that death should exist." But to reach this point, he must reject life as well. He renounces both of them, life and death, as illusions. And he hopes this will save him from the anguish.

Consider again the woman of Sicyon. She looks at things that are partaking of Becoming -- her boyfriend, who will leave in the morning. The fire. The shadow. And she realizes she will miss these things. So she reaches for those objects closest to her which partake most of Being: the charcoal and the tiles of the wall. And she translates that which is Becoming into that which is Being.

We pursue the True Image as a less radical version of Plato's rejectionism. We reject death, as Plato rejects it, but we cannot renounce life. Instead, we say, "This thing, which exists now, is real. I see it now. I love it now. I don't want it to go away." So we reach for whatever we can reach that partakes of Being, and we make a True Image of the thing we see. We make an image using materials that will last longer than we will. That way we can remember, and not die, and once we are gone, and what we saw is gone, we can still go on telling the future what we thought was so precious and so important.

Thank you very much."

Daniel Maidman, Blue Leah #3, 24"x36", oil on canvas, 2011

A version of this talk appeared in the December, 2012 iPad edition of Poets/Artists.