Angel Otero is a Brooklyn-based artist who is known for his sculptural paintings that continue a dialogue with art historical themes while grappling with his own history and sense of self. On the eve of his show at Lehmann Maupin gallery in New York's Chelsea neighborhood, I spoke to the artist over the phone about his life, work, and latest exhibition entitled, Gates of Horn and Ivory. Scroll down for images.

ANGEL OTERO Untitled (Twins), 2013 steel and porcelain two parts, "Circle Top": 37.5 x 21 x 23 inches 95.3 x 53.3 x 58.4 cm "Rounded Triangle Top": 37 x 18 x 23.5 inches 94 x 45.7 x 59.7 cm Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong Photo by Martin Parsekian

KM: In your latest work, you combine porcelain and steel and take them both to their limit. What was an obstacle for you while creating these pieces?

AO: I'm more confident when it comes to two-dimensional works; sculpture transforms as you walk around it, so it changes as you view it. But part of the whole thing in the studio is I get myself into all these good problems.

Were you influenced by Picasso's ceramics at all?

I saw a lot of Picassos, Giacomettis, Baroque era work which I like a lot. Image wise, you just absorb everything and then you mix that with elements more personal. The gates [in Gates of Horn and Ivory] are gates from the house I grew up as a child. You start mixing all these things together, making this big-ass soup and see how they have a conversation or dialogue and react to each other.

Do you consciously put yourself in uncomfortable situations?

[Laughs] My work is very physical and having a physical relationship [with the work] is so important, and not just physically with my body, using paint, and making the objects, but also mentally.

At early college in Puerto Rico I met the Abstract Expressionists and I felt it so literally, it felt so physical -- a physical interaction with the medium. I love the process of making art but making art as a certain story or narrative - I got attached to that. Give me the brush, give me the paint and let me go.

Before attending The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, you were an insurance agent. How did your outlook change once you were able to make art full time?

I didn't trust art as a way of making money. Eventually I thought I needed to escape this reality I was living -- this regular job of selling insurance and going at night and painting. I couldn't sleep thinking of the possibilities of that.

Considering I had never felt snow in my life, and learning about artists like Jeff Koons, Gerhard Richter - I had this contemporary art dialogue I wanted to be in, but instead of making whatever I felt like I had to recognize the moment I was living in art history and what could I do about it.

So what could you do about it?

You are doing something the art world needs in this moment, not what people are expecting. You go in the other direction so that instead of expecting it, [viewers] question themselves more.

Is changing your style terrifying, since so much is at stake?

I try not to let that affect my studio and my process. That's how my paintings came out - I knew it was something that was not rejecting the expectations about painting but I was questioning, kind of challenging it.

I like to step into these weird problems with myself. These sculptures are so problematic for me. They start from such a personal departure, but I don't like the personal to be apparent in the work, so I obscure and re-obscure so it's in another place from where it started from.

For me it's so private; I'm shy about certain subjects relating to my personal life, although I use them as excuses to make art.

Let's talk about Catholicism. In your latest work, the materials suffer; they are squished and constrained.

I think there's a certain suffering [in my work]. This idea as you as a creator is so powerful. The idea of perfection is different for every artist, it comes from deep-ass suffering. You deliver yourself completely to art, almost like you do to a family. You are completely devoted to making this thing to change the world.

Which is why you are directly involved in the making of your art.

My work is definitely very personal. Nowadays we have many incredible artists but they're studio artists. I'm a person who likes my hands dirty. The work has to have energy and the belief I bring to it. I have to be submerged in the art making. I grew up Catholic so I have these weird religious references, but I don't do it because of a religious message -- I just had it all around me when I was young. A lot of my work is about the materiality of memory.

I have a great collection of wooden saints and objects I collect. I enjoy having them close by; I feel kind of safe. I go back to the idea of home, but with art I don't feel that safe, to be honest.

I love painting, that's what I do the most, but I think stepping into uncomfortable grounds is very important in art making.

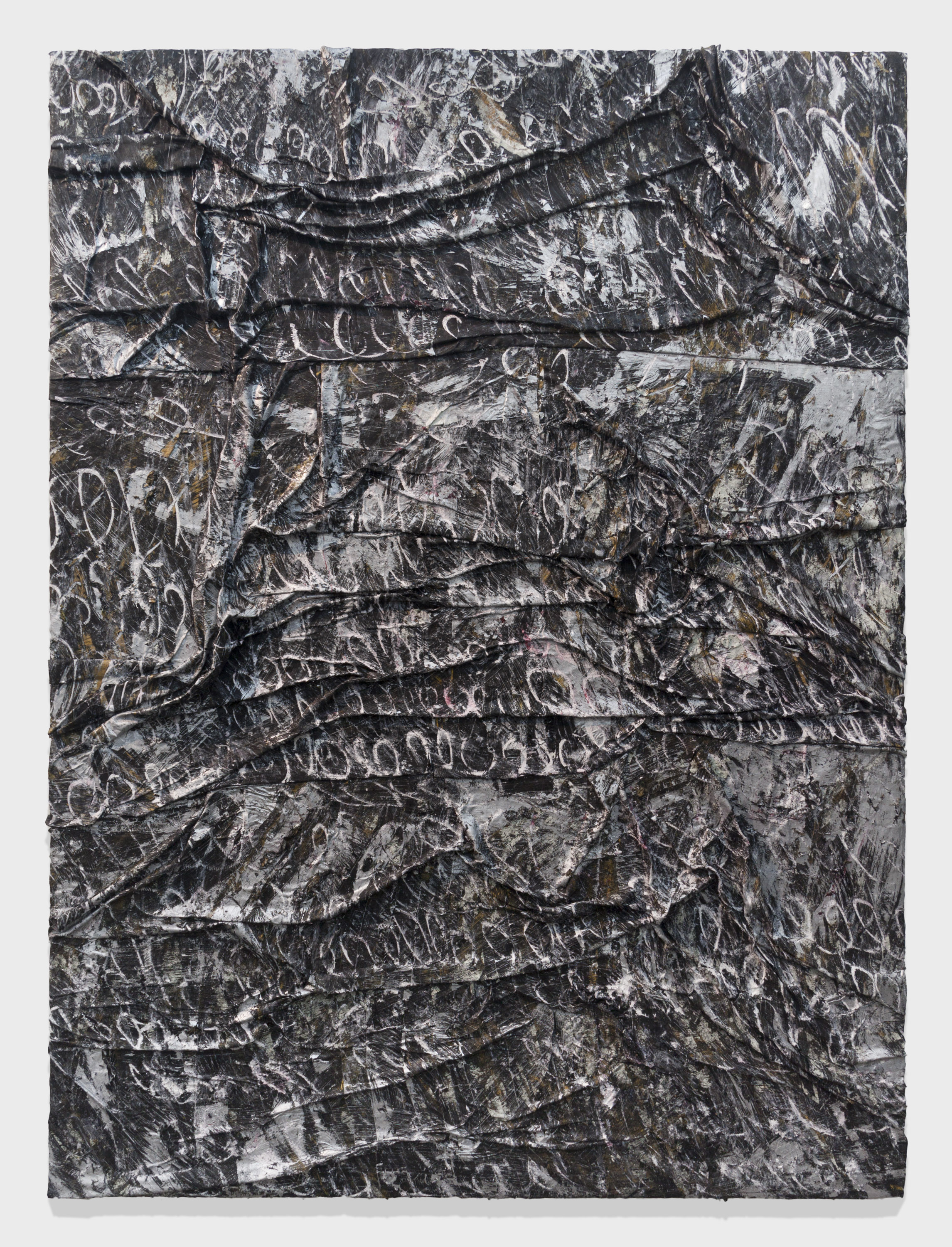

ANGEL OTERO Untitled (SK-MZ), 2013 oil paint and oil paint skins collaged on canvas 96.5 x 72.5 x 4.5 inches 245.1 x 184.2 x 11.4 cm Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong Photo by Martin Parsekian

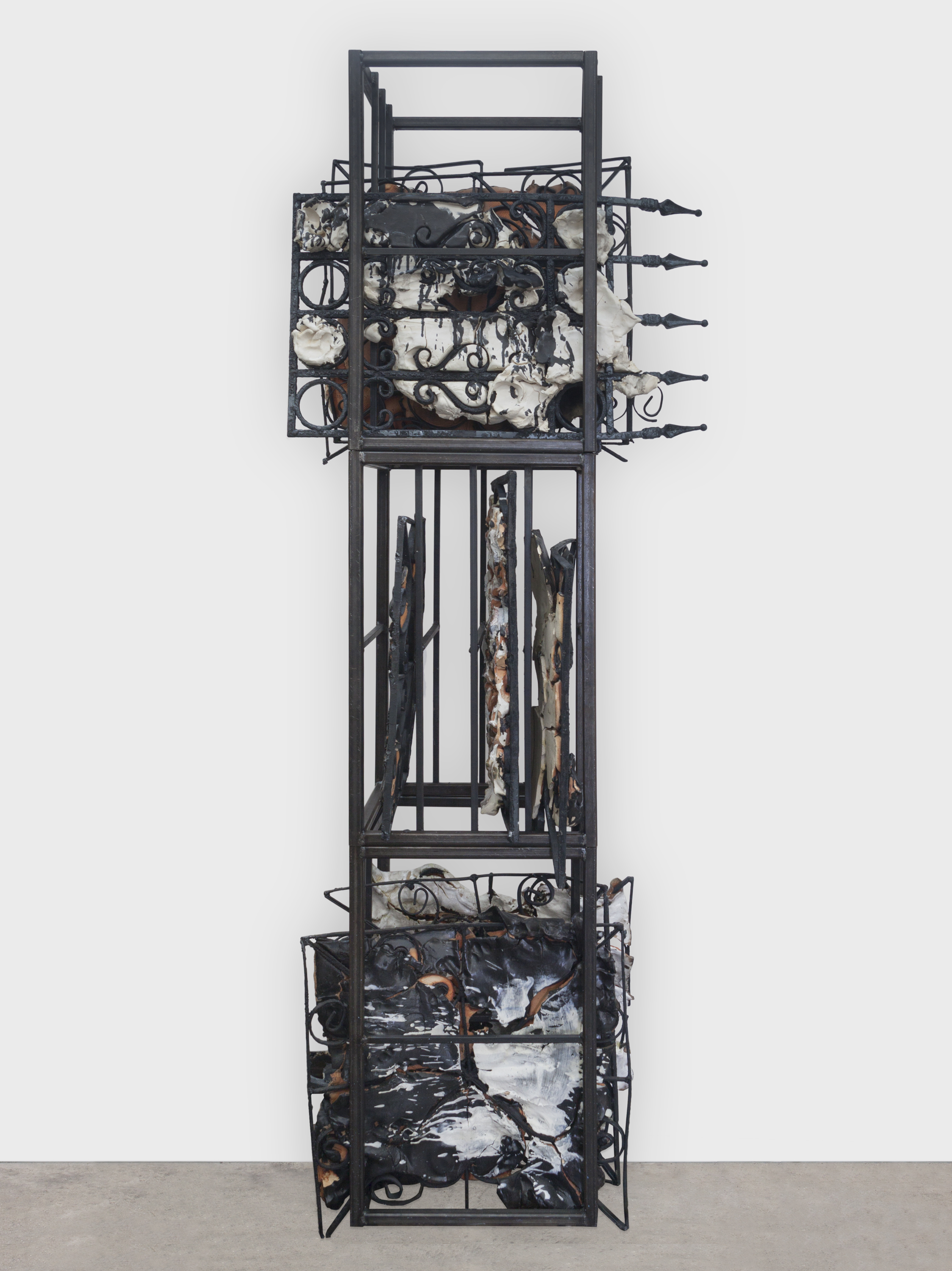

ANGEL OTERO Untitled (Slot Tower A), 2013 steel and porcelain 90 x 32 x 27 inches 228.6 x 81.3 x 68.6 cm Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong Photo by Martin Parsekian

Angel Otero

Gates of Horn and Ivory

September 12 - November 2, 2013

540 West 26th Street