BEIRUT, Lebanon -- Sixty-five years ago, when she was a child, Salwa and her family left their seaside Palestinian home in Jaffa and embarked on a journey that would define their era and that of many Palestinians. As the state of Israel came into being, Palestinians removed from their ancestral homes fled to Syria and other neighboring countries to rebuild their lives.

Now into her eighth decade of life and surrounded by her grandchildren, Salwa finds herself repeating that painful history. Another brutal war has left her -- and tens of thousands of other Palestinians in Syria -- homeless and without a country. Her children and grandchildren, all born in Syria, now share Salwa’s narrative of fleeing their home -- this time to Shatila, an overcrowded refugee camp in Lebanon whose very name resonates as a symbol of Palestinian loss.

For those who have landed here, the future is harder to discern than ever. Often deprived of the right to work or own property inside Lebanon, they languish in the camp while dreaming of a return to Syria -- an increasingly distant dream. Salwa is just one of some 49,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria now in Lebanon, joining more than 820,000 recent Syrian refugees as well as half a million Palestinians who have lived there since 1948.

Salwa’s face is wrinkled and worn, but her blue headscarf makes her tired eyes come to life. She sits on a plastic chair in front of a tiny concrete house in Shatila. Her name, in Arabic, means solace, a name she has lived up to as she guides her family through her second war. Salwa doesn’t say much, but when she speaks, the group goes quiet, hanging on her every word.

"I was afraid," she says. "I didn’t want to see my home destroyed."

As her Syrian home of Yarmouk, the country’s largest unofficial refugee camp, became a battleground, she decided it was once again time to pack up and leave. She fled the besieged camp, near central Damascus, a year ago to live with her son and his family in Beirut’s overcrowded Shatila camp, home to more than 15,000 Palestinian refugees.

Shatila, with its rundown, cramped houses and open sewers, is a far cry from the life she and her family had in Yarmouk. When asked what she misses most, she responds without batting an eye. "Our house," she says. "Our house in Syria is beautiful. Not like here. Now another family is living there. They took our home."

For Salwa, her house in Syria, where her children were born and raised, was her escape from her own dark past. She had lived and created the dream her parents had when they fled to Syria: a dream of a home to call their own. She can never return to her own birthplace of Jaffa, and now she fears she will never see her home in Syria again.

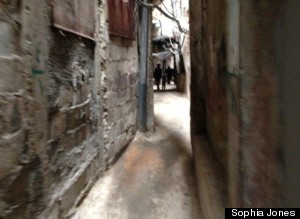

When Salwa walks through Shatila's winding streets, she sees familiar faces -- Palestinian friends and neighbors from Yarmouk who also fled to Lebanon. The camp is in many ways haunted by war, both present and past.

In one alley, a poster hangs of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, but a thick beard is scribbled on his face in black marker. Perhaps it was a mischievous child’s drawing, or perhaps, an ironic political statement.

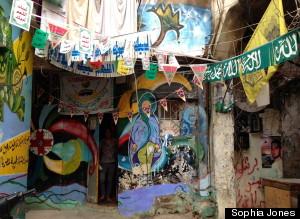

Photos of a young member of the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, a militant group responsible for a wave of terrorist attacks in Israel over the years, are plastered above a doorway of what locals say is a political office. The man looks not a day over 20. The militant organization, labeled a terrorist group by the United States, is mainly financed by Iran and has been based out of Damascus for years. Outside of the office, a man wearing a bulletproof vest stands guard, a semi-automatic rifle dangling from his shoulder.

And on another nearby wall, a child’s painting of a tree rising up from the ground -- its branches seemingly wrapping around the mess of power lines hanging above -- catches the eyes of those who walk past a building known as a martyrs' cemetery. The building was used as a mass grave during the War of the Camps, between 1985 and 1989 in the midst of the Lebanese Civil War, when pro-Syrian fighters besieged Shatila and two other camps in an attempt to weed out Palestinians from Lebanese strongholds.

Yet while Shatila is a name of infamy among Palestinians in the region, it has become a home of necessity. According to Chris Gunness, a spokesman for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, which is responsible for Palestinian refugees, half of the Palestinians crossing from Syria into Lebanon relocate into Palestinian refugee camps (a luxury -- if you can call it that -- not available for refugees of Syrian descent, as Lebanon does not have formal Syrian refugee camps). The U.N. group works to provide cash assistance, education and health programs for the refugees, but any sort of relief effort is incredibly difficult because of the sheer numbers of refugees and the rate at which people are crossing.

Palestinians in Lebanon do not have the same rights as Lebanese citizens, even those who were born in the country to refugee parents. They are legally barred from working in a slew of professions or owning property. Generations of Palestinians are reliant on UNRWA for basic, everyday needs.

But many Palestinian refugees coming from Syria say that UNRWA aid is nowhere to be seen. One older man from Yarmouk, who withheld his name for security concerns, says that he was lucky to find a basic two-room home in Shatila for his family, but that life in the camp is miserable.

"The situation here is so bad," he says, sitting next to his sickly daughter on the floor of a concrete room, where a handful of family members sleep at night. "Here, I have no support."

The father initially flew from Damascus to Cairo, funded by private donors, seeking surgery for injuries caused by a bomb explosion in Syria. But Egypt would not grant his family visas, he said, so he had to return -- an increasingly common story among both Palestinians and Syrians in Egypt. (The country has become a main destination for refugees hoping to take boats to Europe for asylum. As such, the Egyptian government routinely imprisons and deports refugees, sometimes even back to Syria.)

His daughter, suffering from stomach infections, made wedding dresses back in Syria. Now, she sits meekly next to her father, her big brown eyes staring out the door.

Outside, a short walk away, three young Palestinian girls from Syria hold hands in the playground of the camp’s youth center. Before the war, they were strangers. Now, they are family.

While Palestinians fleeing Syria find a strong sense of community in Shatila, and in other Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, tensions are rising, warns social worker Manar Shamieh, who has worked in Shatila all her life. Already scarce essentials like electricity, water, food, jobs and housing are harder to come by with the influx of refugees. Rent is rising, and many long-term residents blame recent arrivals from Syria. Seemingly every day, more Palestinians come to Shatila.

On one winding street in the camp, a fluorescent mural pops out of a concrete wall. Hovering above a painted city reads the Arabic phrase: "How many times will you travel, and for what dream?"

The words are taken from a poem by famed Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, his words a commentary on death, identity and exile.

For Salwa, this may be her final trip. Driven away from her homeland at the beginning of her life, now, in her twilight, she is yet again without a country. But her dream is not dead.

"If the war ended this moment, I would return," she insists, but with a tone suggesting she knows she may never see the end. Until then, Salwa says, she will sit, read her Quran, and "talk to God."