Joanna C. Valente is a remarkable poet whose first book, Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press) was released this past fall. Described by Rattle and Pen, The book "is a collection of character-centric narrative poems in four seasonal sections. The book reads like a non-homogenized Greek chorus version of The Virgin Suicides, and although set in a contemporary time, the poems seem to vibrate with some sort of 70's afterglow."

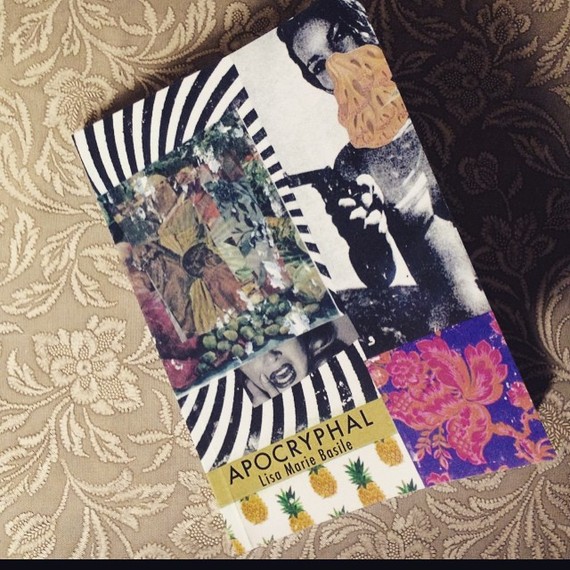

After reading her book (and having my own first full-length, APOCRYPHAL, published at the same time), I felt an immediate connection to her deep interest in the dark and feminine. Her work was similar to my own in a way; we shared an obsession with the body and death, and we both aim to illustrate the role of woman and man.

Joanna and I sat down to ask one another a bit about how we approach feminist writing on sex and death:

LISA MARIE BASILE: In your poem "Her First Love," you write, "He tells her he loves her, that he means it." In the first poem of my "apocrypha" section of my book I write, "My father says he loves her & means it." It seems we are both have some necessity to prove love, and even more so for me, to prove worth. How do men inform this book?

JOANNA C. VALENTE: At the time I started to write Sirs & Madams, I had just been sexually assaulted; obviously, I was not only extremely vulnerable, but I completely lost all sense of confidence -- confidence in myself, which bled into the idea that others could love me. The sense of loss, the loss of love, significantly drives these poems, because at the end of the day, it's all we have as humans. When that sense of confidence is taken, it's utterly devastating and isolating -- it's unnatural.

Of course, not all the male characters are portrayed negatively in the book -- they, too, feel the pervasive loneliness and isolation that sisters feel. Paul and Jacob, in particular, are plagued by it -- I think most people are. Part of my goal as a writer is to illustrate these ordinary, everyday moments of loneliness. Everyone is lost.

LISA MARIE BASILE: The female characters are dangerous in this book -- dangerous in that want, create, hurt and die. Dangerous in that they really do have agency. What responsibility do you think women writers have, if any, to explore empowerment in poetry? Do you think poetry and feminism should be entwined purposefully?

JOANNA C. VALENTE: I don't think women writers have any obligation to do anything but expose their truths. My truth is different than someone else's -- I can only speak from my perspective, which is as a woman in New York City. To explore and expose truths is what artists as a whole seek to do, have sought since humanity's inception. Of course, part of the universal truth of being a woman is portraying female agency and empowerment.

Personally, I do seek to intertwine both, as I was born into a society where the female perspective is still seen as 'other' and obviously I want to expose womanhood and girlhood in real terms, as just as complicated and murky and significant as the male counterpart. And hopefully, to show that both genders aren't that different.

LISA MARIE BASILE: Your use of persona poems is consistent and powerful. Sometimes I use personas because I need them to tell stories I don't want to tell by myself. Do you feel society always tries to combine the art and the artist?

JOANNA C. VALENTE: I feel like our current culture expects that everything we do, whether it is the art we make or the tweets we post, are really "us." If anything, I feel the persona becomes harder to separate from who we are and who we are presenting, even though I feel like creating any type of art or using social media naturally creates a double consciousness.

If anything, I feel like people assume that I must always be writing about myself, which is not true. I definitely use my experiences as fodder, but I tend to warp or change these experiences into new identities. Perhaps it's hard to reconcile that we are capable of multiple identities, as we live in a culture that prefers neat endings and straight lines.

LISA MARIE BASILE: Both of our books confront death and sexuality, and sometimes the poems in both our books marry the two. What is it about sexuality and death -- together -- that speaks to you?

JOANNA C. VALENTE: We are ruled by sex and death completely. Naturally, humans instinctually protect ourselves from death -- we learn to cross the street by looking in both directions, we learn to take safety precautions with almost every activity. So, in a lot of ways, we are obsessed with it. It's always around us, overtly and subconsciously. The act of writing a poem itself is to preserve some part of ourselves, isn't it?

For women, especially, sexuality is complicated and contradictory. The duality of the Madonna and the Magdalene are still prevalent: we are either pure or we are "loose." There's little inbetween. You can't be a "half-slut" or "part good girl." As women, we have little room for complication in mainstream culture, and yet, that is far from the truth. Having had a religious upbringing, I was surrounded by Christian iconography from a young age; the strangeness and mysteriousness of it enthralled me. As a huge part of American culture is entrenched in Christianity, it's definitely an obsession for me. Death, loss, and suffering are huge parts of the religion; in a lot of ways, sexuality is forbidden and mysterious, as is death, so the two become intertwined in a lot of ways.

Going through menstruation, sexual awakening, childbirth, motherhood and aging all involve a sense of a loss, or small deaths. We lose parts of ourselves as we mature; every month we lose blood. Perhaps it's only natural for me to link both together, as nature has already done that for us. In my book, the sisters are aware of this, even if only subconsciously, and like all people, we crave what is forbidden. We want the mysterious. It's why we like watching films and television so much. We need to know what's next.

JOANNA C. VALENTE: Your work often deals with female sexuality on a metaphysical level. On page 43, the speaker of your poem states: "I get paid for the naked... when we are done I wear the curtains and the light likes me like a child." Why are you drawn to undressing your speaker, so to speak? Do you often feel like this is a way for you to examine yourself?

LISA MARIE BASILE: I suppose the question, for me, is why would I keep my speaker dressed? The more uncomfortable I am, the more honesty I tend to create, I think. It might sound strange, but I can't live life without letting my speakers behave as badly as I have or want to during parts of my life. There is a certain part of me that is drawn toward the ugly, I think. I am drawn toward the exploration of badness and what makes something bad. I want to know why being bad happens. I want to know why being nude is wrong. I want to know why these vulgar acts can't always be hand in hand with beauty. I suppose I do enter into it metaphysically, in that I aim to deconstruct. Then again, I feel too many women -- poets or not -- are asked to explain themselves, their bodies, their desires. I want to present a world which is already stripped down; its foundation is that it does what it wants. I would like that of my life in many ways.

JOANNA C. VALENTE: Do you ever find yourself having a double consciousness, so to speak, where you often have to switch from your poet persona to your "work" or "family" persona? As a teacher, I find myself in this situation all of the time, especially as I tend to focus on female sexuality. Do you think people have preconceived notions about you?

LISA MARIE BASILE: I think about this more and more as I get older. As we grow professionally, romantically, etc, we are expected to behave in certain ways. We dress certain ways for interviews. We speak certain ways at work. We are to keep our potty mouths shut at the dinner party. All of that. I've always had a bit of a problem being outspoken, especially in my writing, and I do have a huge fear that everything I write will be taken literally. I have seen it happen many times: society often cannot separate the art from the artist. People project. I suppose the woman especially has always been a blank canvas for our morals, but it should not be that way. Nor should art.

I think, adding another level, that branding is a huge part of the poet's career as a poet. Once you submit your work to a literary journal, you have sort of relinquished a bit of privacy. You become a public entity, in a way. Of course, there will always be the people who judge you. I would say the literary community is very progressive, but there have been plenty of instances where women and men poets alike have been shamed for any number of things -- their looks, their writing. Recently, someone read somewhere that I taught a class called "sex poetics" and said to me, "how can you not actually expect to be called a whore?" These are real words. Real problems.

I don't want to have to think about if my poem is "too" this or "too" that. I don't want to have to think about how art affects our real lives, but I suppose it does and it's worth fighting against in most cases.

JOANNA C. VALENTE: Javi reminds me of Nadja from Andre Breton's novel. He seems elusive, unreal, a ghost. On page 25, the speaker says: "finding a man/is as easy as dowsing rods." What are the role of men in this book?

LISA MARIE BASILE: Men -- or the ideas of ghostly, unattainable, predatory and nurturing men -- have always played a major role in all of my work. They are very much like Nadja, actually! The men serve a specific purpose: they help me ask and answer questions. They help me recognize I don't need their answers. They help me break the mystery we all build. They also help me confront the ones I've known and am obsessed by.

Sometimes, they exist as sexual objects or backdrops to a sexual situation, allowing me to subvert the ways we objectify the body and the self. If it sounds like they're being used as a prop, I don't mean that. I mean that I'm truly fascinated with them. I am truly fascinated with my own fascination with them, but ultimately it's me with the pen.

Joanna C. Valente is a human who received her MFA in writing at Sarah Lawrence College. She is the author of Sirs & Madams (Aldrich Press). Some of her work appears in The Paris-American, The Destroyer, The Atlas Review, and others. In 2011, she received the American Society of Poet’s Prize. She founded and currently edits Yes, Poetry, and is the Managing Editor and a staff writer for Luna Luna Magazine. She resides in Brooklyn, New York. More can be found at http://joannavalente.com.

Lisa Marie Basile is the author of APOCRYPHAL, along with two chapbooks, Andalucia and War/lock (February, 2015). She is the editor-in-chief of Luna Luna Magazine and her poetry and other work can be seen in PANK, the Tin House blog, The Nervous Breakdown, The Huffington Post, Best American Poetry, PEN American Center, Dusie, and the Ampersand Review, among others. She's been profiled in The New York Daily News, Amy Poehler's Smart Girls, Poets & Artists Magazine, Relapse Magazine and others. Lisa Marie Basile holds an MFA from The New School.