Contributed Reporting by Captain Sarah Cavanagh

Photos by Rose Marie Cromwell

The color of the sea shifts from light to dark blue, almost purple. We are now in the Gulf Stream somewhere between Key West and Havana. The wind blows from the north and the current flows against it. Where the two meet, the waves grow upward and we roll like a 40 foot bobber with a sail on it. Only 90 miles of ocean separate the United States from Cuba, but don't let anyone fool you into thinking there isn't plenty of beautiful and dangerous water out there.

Twenty-two hours after leaving Key West, we arrived at the Hemingway Marina in Havana, exhausted and still feeling the effects of rough seas. At the marina's entrance, three Cuban government officials boarded our vessel and inspected, rather casually, the fruits and vegetables we had onboard. An old doctor in a guayabera also took our temperature and asked a few basic health questions:

"Have you been sick lately?"

"No."

"Very good."

The whole inspection took less than 15 minutes: a few signatures, a round of smiles and handshakes, and we were legally in the Republic of Cuba.

Motoring further into the marina, it was obvious that we were not the only the sailboat making this journey. The Hemingway Marina looked like a forest of masts. Two days earlier, 46 sailboats began a race from Miami to Havana. We, inadvertently, arrived at the tail end of the regatta.

Since the shift in U.S.-Cuban relations, recreational boaters from Florida have been literally racing to Havana. This past winter there were three regattas from Florida to Havana: one from Pensacola; another from Key West; and this one, from Miami. Motor-boaters and fishermen have joined the race south as well. The Hemingway Billfish Tournament scheduled for June 13 this year already has over 50 American boats signed up, and expects more than 100 American boats in the competition. In the 2015 tournament, in contrast, only 14 American boats participated.

Visitor numbers from the United States to Cuba increased by over 70 percent in 2015, compared to the previous year. And boaters have become part of this new tourist boom. The growth continues. In the first quarter of 2016, hotels in Havana filled up; the Hemingway Marina received a record number of boats; and bars and restaurants across the city literally ran out of beer.

It's a surreal convergence of boaters, tourism, and realigning geopolitics at the Hemingway Marina.

After going through Cuban immigration and customs, we docked at Canal 1, a long trough similar to the limestone-cut canals of South Florida. Astern we met our new neighbors; a meet-up group from Miami who sailed a big bulky ketch (a two-masted sailboat). They came in dead last in the regatta, and during the trip, they had to deal with a mutinous crewmember who threw the captain's tools overboard. Despite that odd setback and their poor showing, they were in high spirits when we met. In the afternoon, with the wind still blowing strong out of the north, they drank beers and cheerfully walked the docks. Just behind them was another boat, a catamaran, sailed by four older men from Georgia and Florida, sporting Hemingway-esque grey beards, with beers in hand.

During that first day in the marina, in every direction we looked, there were American sailors chatting, laughing, unloading their gear, and having an early drink. It felt like a scene from pre-revolutionary Cuba, as if the gringos had never left.

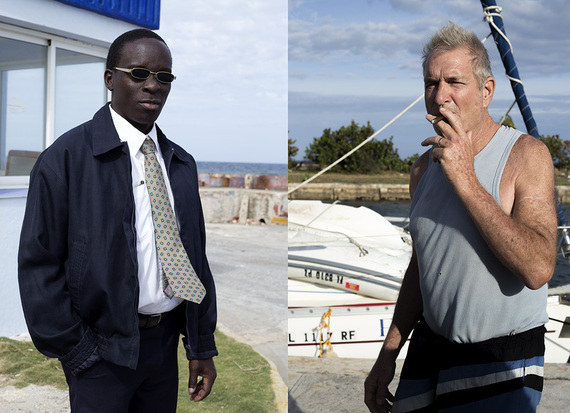

Scattered in-between the race boats we also met what the sailing world calls "cruisers," that is, sailors moving from one harbor or anchorage to the next, not particularly interested in how fast they got there. Docked in front of us was a salty looking fellow by the name of George, living on a steel boat sailed out of New Orleans. He'd been coming down the last few winters, he explained, bringing in cheap clothes and goods for his Cuban girlfriend to sell in the streets of Havana. Exchanging tales with a group of sailors, he was full of jokes about how bad of a sailor he was - "always getting seasick" - and how his Cuban lady liked to sleep with all the other foreigners. At the marina, there were plenty of put-together and proud cruisers, but there were also quite a few of the George-type who seemed to wash into tropical ports and increasingly into Havana.

Cuban officials, however, have been optimistic about the return of American boaters. One dock master, a former teacher, explained, "We still like socialism, but not like Russia. We want socialism with motivation."

Two days after our arrival, we crashed the Miami-to-Havana Regatta's award ceremony to see what this updated "socialism with motivation" looked like. That evening the crowd, made up mostly of white men from the United States, was in a rowdy and festive mood. After a few hours of mingling and complimentary Cuba libres and mojitos, the race organizers spoke some celebratory words about the inaugural Miami to Havana race, and the crowd of sailors hooted and hollered like a victorious football team. The evening's hero, when they all really cheered, was when a grey-haired racer came on stage, who had sailed the St. Petersburg, Florida to Havana regatta in 1954, before the revolution. (To extend the football game analogy, imagine a beloved retired player walking onto the field at halftime. He seemed to represent past glories, and perhaps their return.)

Next up on the program was a speech by the Commodore of the Hemingway Yacht Club, José Miguel Díaz Escrich, looking dignified with a clean shave, his silver hair slicked back, wearing fine khakis and a crisp blue blazer. His dress and his demeanor contrasted sharply with the casual flip-flops and T-shirts of his American guests. As the Commodore began to speak, the crowd of sailors grew silent for the first time that evening. Pausing intermittently for the translator to catch up, the Commodore told the audience, "It's never too late to make your dreams come true!" The re-establishment of U.S.-Cuban relations and the arrival of more and more visitors, he said, tearing up, was a dream come true. After sixty years of absence, U.S. boaters were finally returning to the island. At the end of his emotional speech, the racers lined up with their yacht club flags to take a picture with the old Commodore, a loyal revolutionary now overseeing the influx of American sailors and tourists.

The regatta party took place on Valentine's Day. Hundreds of American men had gathered in the Hemingway Marina to give themselves trophies for sailing from Miami to Havana. They drank free booze and consumed giant pigs at the yacht club while most of their loved ones waited at home.

As two guajiro cooks (from the countryside) delivered the first pig, the Commodore stood back, smiling and looking regal, as the red-faced sailors shouted and laughed and charged the table like sharks swarming a floating carcass. Later on that evening, many of the sailors broke into smaller groups and went out to the Havana bars, where all is seemingly permissible for American visitors. The whispered word at the yacht club is that the Cuban police have been warned by high-ranking party officials that the new gringo tourists are not to be harassed. As a group of insurance brokers/ sailors explained to me, as they headed out to continue to the party and find girls, "This country is so f****d up." Perhaps, though, the island is increasingly attracting people drawn to "f****d up" behavior...

The morning after the race, we witnessed another telling sight. A crowd of Cubans and foreigners jumped into the water and swam in their own race in the canals around those very expensive boats. Although an internationally recognized event and perhaps fun for its participants, the aquatic juxtaposition was hard to ignore. Americans hung out on million-dollar boats and below them, locals in swimsuits raced in dirty marina water.

The Miami to Havana race was meant to have a formal element of cultural exchange, but somehow those plans disappeared. Cuban students were scheduled to sail with the racers from the marina entrance to the Morro Castle some 9 kilometers away. The rumor on the dock, however, was that someone high up in the Cuban government didn't like the idea and shut it down.

While the revolutionary government reforms its policies to welcome more foreign boaters, it maintains a rather draconian maritime policy for Cuban nationals. It's illegal for most Cubans to board a foreign-owned vessel. Getting on a boat is a difficult thing to do, and owning one is even harder. "If we could have boats," a friend from Havana once told me, "we would all leave to Florida." Another friend, a respected academic, used to go out on her father's boat when she was a kid. But after the revolution, the state nationalized the family boat and took it away. "Today we're not allowed to set foot on a boat," she explained. Her eighteen-year old son, like the overwhelming majority of young people living on the island, knows nothing about boats. (The old man and the sea is lacking modern descendants.)

What does it mean for Americans to be able to sail and now fish in Cuban waters, while the average Cuban is prohibited from setting foot on a recreational boat? "Perhaps," a Havana cab driver reasoned, "we've suffered all these years, so that Cuba could become the most famous and important country in Latin America." That sounds poetic, but it isn't very satisfying to most Havana residents.

In anticipation of the embargo's end and the potential shift in immigration policies, a new wave of Cubans have been trying to get off the island. In February 2016, the same month of the Miami to Havana race, the U.S. Coast Guard documented 269 Cuban migrants trying to cross the Gulf Stream to Florida. Many more likely went undetected. Captain Mark Gordon of the U.S. Coast Guard made it clear that "immigration policies have not changed and we urge people not to take to the ocean in unseaworthy vessels. It is illegal and extremely dangerous." The Gulf Stream, you see, is traveled by both Cubans and Americans, although on dramatically different vessels, with dramatically different goals, and with dramatically different legal and governmental support. If it's intense to be out in those big waves on a well-designed sailboat, imagine what it's like on a raft or a small, leaky fishing vessel, and to do it clandestinely.

Two weeks after arriving to Havana, we sailed back to Key West, guided by an east wind and aided by the current. To the north, across this stretch of sea, it's a different, more established tourist and boating vibe. In Key West, after checking in with customs, we walked the docks near Mallory Square and watched the tourist crowds. "Tell your mom you love her and then give me a twenty," I hear a guy shout to a group of amused visitors. A few yards away a tattooed street performer squeezed himself through a broken tennis racket, while a trained cat jumped over the head of a recruited tourist ('eee" was the command). The tourism industry has come to dominate the little island of Key West. And as we wander the streets, I wonder: is this what's in store for Havana?

The sailboats, and sports fishermen, and tourists come and go as they please across the Gulf Stream, and meanwhile somewhere along the current, another round of Cuban rafters face the waves and the wind.