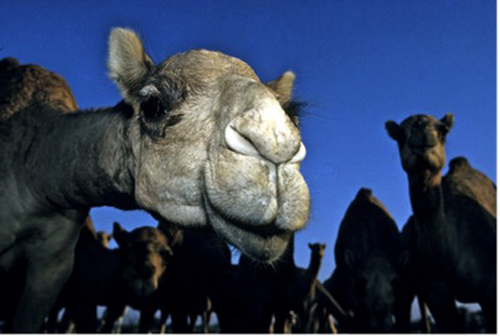

Photo by Pamela Roberson

"The croak of the raven is not heard,

And the lion does not devour, the wolf does not rend the lamb,

The dove does not mourn, there is no widow, no sickness,

No old age, no lamentation."

~ Anonymous description of the island "30 double hours south of Babylona, in the midst of the sea of the rising sun," third millennium B.C.

It was a place of legend called Dilmun.

The Sumerians, who hailed from what is today southern Iraq, described the island of Dilmun as the Garden of Eden, the lush plot where innocence was forever lost. On a hot June in 1932, a steel bit pierced a layer of blue shale 2000 feet down, and a jet-black torrent erupted. It was the first oil discovered in the Middle East, the beginning of an age. And, for some, there was a sense that that moment marked the beginning of an end.

Tonight the situation seems a nightmare from 1001 Arabian nights. It is 10 pm. I am standing in the immigration hall at the Bahrain International Airport after twenty hours of flying, and the official tells me there is no visa waiting, no one to meet me, and that nobody has ever heard of me. Sorry. Ana asif.

"Hidden like a fish in the sea," the Sumerians described the island of Bahrain around 2500 B.C. I have no names, no phone numbers, just stateside assurances that everything was arranged, that I would be a guest of the royal family. Lost in an algebraic equation that might or might not be solved.

After an hour wandering the terminal, asking advice from policemen, passersby, the cleaning staff, I decide to call the man who set up this visit, Mohamed Hakki in Washington, D.C., the former press secretary to Anwar Sadat. I connect in a snap. He gives me the name of the Prime Minister's press secretary, Al Sayed Al-Bably, and tells me to call him at home. "Things are fine, not to worry," Hakki assures.

Bahrain, like much of the Middle East and North Africa, is in the throes of a pro-democracy movement, and in this fierce swirl I accepted an invitation to visit the paramecium-shaped island in the Gulf to explore its tourism potential.

Bahrain, about one-sixth the size of Yosemite National Park, is really an archipelago in the lower end of the Persian...excuse me....I mean Arabian Gulf (Sunni-ruled Bahrain, because of the theological and political differences with Shiite Iran, insists on calling the surrounding waters the Arabian Gulf. Iraq, for the same reasons, does as well) with an inexact number of islands, as the count is ever-changing. By dredging the shallow seabed, new islands are always on the rise, created as seen fit. Bahrain has been a port of call on sea routes between Mesopotamia and India for over 20,000 years, and had flown the flags of a dozen nations until its independence from Britain in 1971. Today, it is among the most cosmopolitan nations in the Gulf region, where women often hold jobs and drive cars, and men drink freely in swank bars. It is, by some reckonings, a liberal oasis in an increasingly conservative desert.

I reach Al Sayed at home. He apologizes for the inconvenience, explains that the prime minister's plane arrived from Cleveland moments before my Cathay Pacific flight, and that all attention had been diverted to matters of State. He would arrange for the visa and pick me up in an hour.

It is midnight at the oasis when Sayed fetches me. In minutes we are speeding down the causeway connecting the island of Muharraq to the main island of Bahrain. In Manama, a fantasy city built of the sands of oil money, we wind through quiet, dark, curbed and guttered streets. One structure stands out: a squat building lined with colored lights. An Arabic song wafts through the window, the sound of men chanting like birds of prey. A marriage celebration, says Al Sayed.

He takes me to the Diplomat Hotel, but it is full of Saudis and American militia. No rooms. Finally, we find a room at the Hilton, and Sayed bids goodbye, saying that since it is now Friday, the holy day, I will not hear from anybody. I should just relax. Not to worry.

I spend Friday worrying. Trying to move into a mood, I eat a pita-bread sandwich filled with spiced kebabs at the Al Wasmeyyah coffee shop, among dozens of soldiers in unwrinkled chocolate-chip-colored desert camouflage pants and T-shirts. That night I wander into the Hilton disco, and there stare from the sidelines at a group of Arabs dressed like biblical figures shaking their booties to a Filipino pop group performing Madonna's "Like a Prayer."

Saturday morning I awake predawn to the harsh amplified ululation of the first prayer call. I wander outside to a cool, arid wind and the soft blue of a desert dawn. Beyond the hotel walls I can see a series of construction cranes, the national birds of Bahrain.

When I return I get a call from Sheikh Rashid Bin Khalifa Al-Khalifa, nephew to the emir, son-in-law to the prime minister, and the Undersecretary for Tourism, who warmly welcomes me to Bahrain. He will be over in an hour to pick me up. This, I know, is an honor, and I rifle through my bag to find a fresh shirt. The Al-Khalifa family has ruled Bahrain for over 200 years. An offshoot of the great Anaiza tribe of northern Arabia, they are related to the Al-Sabah family of Kuwait. Sheikh Ahmed Al-Khalifa, "The Conquerer," drove out the Persian garrison controlling Bahrain in 1782, establishing the dynasty that continues today.

On schedule a shiny new BMW 750i pulls up, and out jumps a boyish, enthusiastic sheikh. He wears a long, white cotton thobe, bleached and pressed to a dazzling crispness, and a red-checked ghutra headdress held in place by the black agal headband, the wool cord once used by the Bedouins to hobble their camels. The young sheikh drives me to his office on Al-Khalifa Avenue, where we are served cardamom-flavored coffee poured from a brass urn into small, handleless cups. Sheikh Rashid then explains that the oil wells in his emirate are predicted to run dry in a few years, the natural gas reserves not long after, and the country is looking to diversity, to establish non-oil-based industries. Offshore banking is a bright spot, and more than a hundred banks and financial institutions have opened doors in recent years, but confidence in the island's future as a safe money haven has eroded in recent months.

Tourism is something the royal family believes has potential. With money services they had hoped to become the Hong Kong of the Middle East, but with the shifting sands of the region, they now wonder if they might become the Bali of the Gulf. Rashid asks if I might take a look, offer some thoughts and suggestions. Of course, and I produce a list of sites I hope to visit. At the bottom I ask about camping, and perhaps climbing the island's highest peak. Not to worry, he will arrange everything.

The sheikh introduces me to my traveling companions for the next several days: Fareed Hassan, a green-eyed guide; Abbas, our olive-skinned, tie-wearing driver; and the white-turbaned and -robed Hakkim, a liaison officer from the Ministry of Information, on board to be sure I don't somehow breach national security.

We start off with a bong. Fareed takes me in the labyrinthine, ocher-colored world of the market, to a traditional coffee shop, where he orders up some tobacco packed in a gidu (an Alice in Wonderland caterpillar-smoking type hookah). In a room dense with smoke we sit back and puff until my head spins. At last I stagger to the van and Abbas begins driving to the middle of the island to visit The Tree of Life. While whizzing down the perfectly flat highway in our air-conditioned Mitsubishi L300 van with the power roll bubbletop, we run into a traffic jam. The emir's camels are crossing the road. Then, plainly visible on both sides of the highway, the great age of the world seems to be revealed with sudden poignancy: we pass the famous burial mounds, the largest prehistoric cemetery in the world, a virtual city of dead people dating back to 3000 B.C. Over 150,000 people were buried here in a vast field of mudpie-like mounds called tumuli, stretching far as the eye can see. The dead lie thicker than the living among these hills.

This is the first post in a four-part series. Read part two here.