Christopher Gobler and his team at Stony Brook University's School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences have provided much of the essential research underpinning our current efforts to diagnose Long Island's environmental ills so that we can develop solutions to them.

If Long Island does manage to resolve its water issues and become a sustainable place to live, it will be in part because Prof. Christopher Gobler and his team were able to diagnose the causes of our ground water pollution and with that point us toward the right solutions.

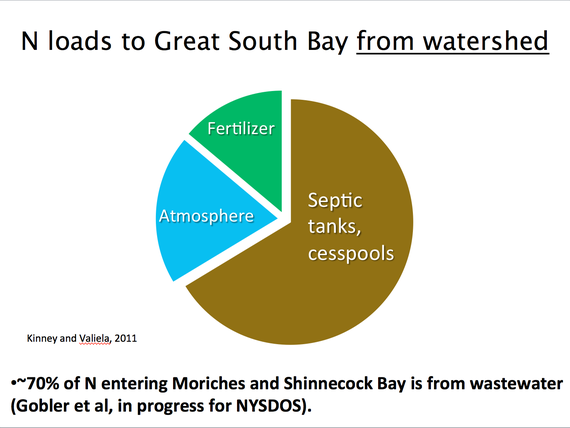

Chris and his team helped link septic tank seepage to the nitrogen fueled algal blooms around Long Island. Today, we know that we need to deal with the 500,000 septic tanks on Long Island if we are to save our bays, rivers, ponds, and marshes, and preserve our drinking water. Today, as various scientific experts and public officials grapple, along with our environmental non profits and the public with the question of how we address our water quality issues, Gobler's work is essential in charting the right path.

Through his work we just learned that there is a direct link between high nitrogen and the collapse of our marshes. Since Suffolk County is in the middle of rolling out a strategy to rebuild stronger, better, and smarter post Sandy, his work would suggest that Long Island needs to tackle the nitrogen pollution problem if it is going to have a coastline that is resilient, that has thick marshes and seagrass and shellfish beds. Chris' research brings us to this point.

Chris where are you from?

I was born in Port Jefferson and raised in South Setauket.

What was Long Island like when you were a kid?

Growing up on Long Island, I fished with my grandfather, sailing with my father, and went to the beach with friends and family. We lived like Islanders.

Where did you go to school?

I graduated from Ward Melville high school, the University of Delaware with a BA in Biology, and Stony Brook University with an MS in Marine Environmental Science and a PhD in Coastal Oceanography.

What is your main area of expertise?

My research examines the functioning of aquatic ecosystems and how that functioning can be effected by man or can affect man. I investigate harmful algal blooms (HABs) that can harm or be lethal to marine life and even humans.

Another research focus within my group is the effects of climate change effects on coastal ecosystems including studies investigating how future and current coastal ocean acidification effects the survival and performance of early life stage bivalves and fish.

A final area of interest is investigating how anthropogenic activities such as eutrophication and the over-harvesting of fisheries alters the natural ecological functioning of coastal ecosystems.

How did you get interested in that?

During college, I came home one summer and was attending a presentation by a bayman from Great South Bay. It was about 1990. He explained that his father was a bayman and his grandfather was a bayman, and he wanted his son to be a bayman. Then he explained that the clam population in Great South Bay collapsed and that he now was looking for another line of work and encouraging his son to do the same. When I asked him why, all he could say was brown tide. The rest is history, as both of my graduate degrees studied brown tide and I still do to this day.

That's really finding your inspiration. What if the son's son could work the bay some day? With that, what is causing this, what is the biggest threat to Long Island's environment? What's the second?

The overloading of nitrogen in poorly flushed bays, harbors, and estuaries. Because nitrogen controls the growth of primary producers [algae in this case], an excessive load has a strong effect on them.

The excess nitrogen weakens the salt marshes that provide our first line of defense against coastal storms.

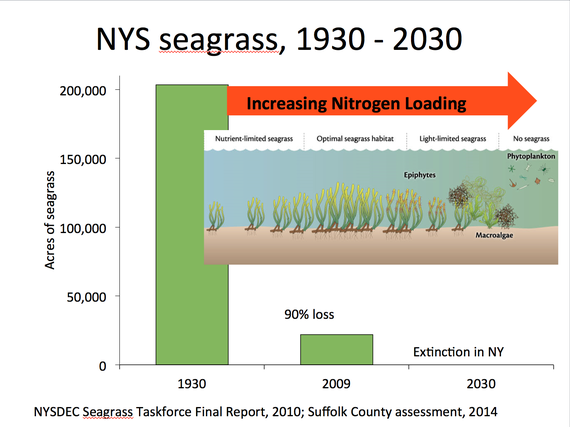

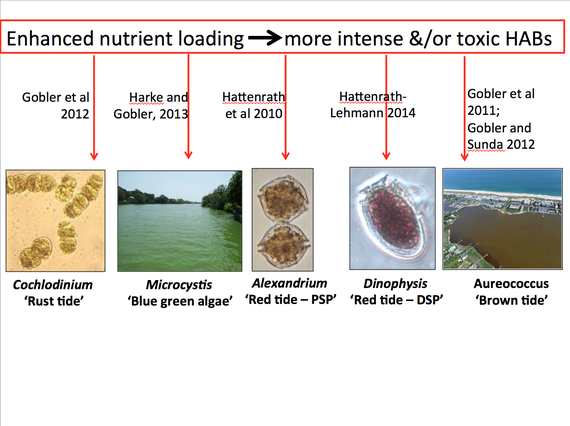

It stimulates harmful algal blooms -brown tides, red tides, rust tides, blue green algae. These blooms can be lethal to marine life and can kill of seagrass which was once a critical refuge habitat that supported many fish and shellfish.

The die-off of algal blooms can starve water of oxygen and make it more acidic. For all of these reasons, key fisheries on Long Island such as hard clams and scallops have collapsed and are at 1% of peak landings.

Climate change is another threat, but in many ways its out of our local control. Hence, we need to address the nitrogen issue now to make our bays resilient against climate change.

What is an algal bloom?

It is an growth of algae beyond the 'average' level. In some cases, algal blooms can be beneficial in supporting marine food webs. However, when fueled by excessive nitrogen loads or comprised of toxic or harmful species, these blooms can lead to the harm described above.

When was the first time you saw one, and how many have you seen since in our waters?

Well, my mom recently unearthed a photo from 1974 showing me picking up some Ulva from West Meadow Beach on Long Island Sound. Beyond that, I began my studies at Stony Brook in 1992.

What do algal blooms do to our bays and ponds?

As mentioned, they can be harmful to marine life or humans. One particular species that grows locally, Alexandrium, contains saxitoxin, a neurotoxin that causes paralytic shellfish poisoning. These toxins can accumulate in shellfish and cause weakens, paralysis, or death in humans when consumed. In 2012 alone, 13,000 acres of Long Island bays were closed to shellfishing due to PSP toxicity.

How do algal blooms and increased nitrogen render Long Island more vulnerable to storms and flooding?

The biggest threat there is the weakening of salt marshes. Salt marshes protect our barrier islands and protect our mainland from flooding, storm surge, and waves. We've lost 20-80% of salt marshes across Long Island since 1974 and we now know that nitrogen loading had a big part in that loss, as high nitrogen loading causes salt marshes to no longer invest in a dense root system. With weak roots, salt marsh plants collapse and die. During Hurricane Sandy, the regions of Long Island without salt marshes like Long Beach were devastated. Near by regions with salt marshes and dunes fared far better.

Is there any way to stop them, i.e. Can Long Island Be Saved? If Long Island did everything right -- fixed its sewage infrastructure by dealing with its 500,000 septic tanks, rebuilt and modernized its sewage treatment plants, went with organic fertilizer, went away from pesticides, disposed of household chemicals and pesticides properly, how much/how quickly could our local environment bounce back?

It would take time in some regions, but the science and past experience tells us that lowering nitrogen loads in regions with excessive nitrogen will reverse the negative trends I have described.

What is your favorite marine / aquatic creature?

Algae, of course.