It is clear that for a time, Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz were mad crazy for each other, that sex was a great deal on their minds and that it was all mixed up with their art, which it often is.

Stieglitz, who had been a collector of erotic photographs, began to take a series of nude photographs of O'Keeffe that were spectacularly intimate (There is no one better than O'Keeffe for showing that naturally voluptuous breasts are better than the ones made in the doctor's office) which he ultimately exhibited in a retrospective of his work to much public notoriety.

Nobody ever said it was easy to be a muse.

Alfred Stieglitz -- Georgia O'Keeffe: A Portrait (1918)

But having thus been "branded" the sexy artist, O'Keeffe resisted the narrowcast and backed away from being photographed nude and "sequestered" her abstract work -- her earliest passion -- and gave way to more realistic drawing of bones and mountains and flowers.

Later in life when she had fled the New York art and social scene and was further away from Stieglitz's powerful influence she went back to this kind of art which had deep personal meaning for her.

Though I had spent time studying O'Keeffe's work (I helped launch the PBS documentary made on her during her lifetime by Perry Miller Adato at WNET) and her singular interpretation of the feminine sexual experience, this exhibition was revelatory for me. O'Keeffe is someone who can stand very much on her own. Yet her relationship with the talented men who gravitated toward her is a worthy subject. This past summer, her work -- always a blockbuster draw for museums -- was featured on both coasts, paired with work of Ansel Adams in San Francisco and Arthur Dove in Williamstown. Yet the very early abstractions at the Whitney are the most haunting, and I prefer them to the more overtly symbolic images.

Senior Curatorial Assistant Sasha Nicholas spent two years at the Beinecke Library at Yale studying the letters between Stieglitz and O'Keeffe which were unsealed in 2006. A selection is printed in the fascinating catalog.

Besides seeing that Stieglitz is deeply under her skin and on her mind, they show the thrill of meeting someone who understands what you are trying to achieve in your work, who then champions it, and then the heartbreak of having him pull in another direction. They show that O'Keeffe needed to hike and be out in the natural world, whether at Lake George or in New Mexico, Texas or Colorado, but that she also loved living in the very first residential skyscraper in Manhattan; that she once cherished New York and the thrill of being connected to so many other artists and talents as much as she came to love the isolation of the Southwest.

Culture Zohn: The letters show an O'Keeffe who was both devoted to Stieglitz and somewhat in thrall to him. As George Putnam was to Amelia Earhart, so Stieglitz seems to have been to O'Keeffe. What drives talented women to be so devoted to their mentors? Is it commerce? Does this phenomenon still exist today?

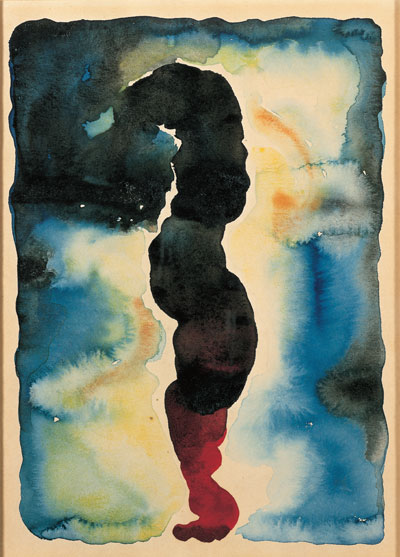

Sasha Nicholas: O'Keeffe certainly was enthralled with Stieglitz in the beginning. She was in Canyon, Texas, making these radically innovative charcoals and watercolors with virtually no audience for them.

Georgia O'Keeffe -- Early Abstraction (1915)

Even in New York, her art would have been radical, and in Texas, no one understood it at all. Her correspondence with Stieglitz -- to receive such enthusiastic feedback from the man who was the keystone of the New York art world -- gave her the encouragement to keep making art. I think her devotion to him sprang from that feeling rather than from commerce. O'Keeffe's early abstractions were her vehicle for articulating her most personal emotions and experiences. Her sense that Stieglitz understood what she was trying to say with them gave her confidence. It created a permanent bond.

CZ: It must have been shocking and disappointing to her that Stieglitz's nude photographs of her led critics and the public to see her work as sexual above all else. Yet she both traded on this sexuality and rejected it. How did this affect her work?

SN: The sexual interpretations led O'Keeffe to transform her abstractions, not to mention her public persona. Stieglitz showed the nude portraits in a retrospective of his work, several years before her oils were introduced to the public. The photographs turned O'Keeffe into a celebrity overnight. That was a marketing coup for Stieglitz, but for O'Keeffe, it meant that everyone knew of her without having seen her work. When they did finally see it, all they saw was the sexually liberated woman of the photographs. That was mortifying to her. She probably felt she had been pigeonholed and that perhaps, for the critics, all of the sexual innuendo was a way of suppressing her radicality. After that, she began making abstractions that were tethered to recognizable subjects. That allowed her to blame the sexual interpretations on the viewer, even while the works still remain incredibly sensual and provocative. She also stopped posing the the nude. She began to appear in photographs as the austere, independent, almost nun-like figure that we know today. The move to New Mexico solidified that image.

CZ: O'Keeffe had to eventually flee his orbit, so powerful was his influence. As soon as she did, he had a nervous breakdown and then took up with Dorothy Norman, a 22yr old. How much do you think he really valued O'Keeffe? We don't have his answers to her letters in the catalog.

SN: O'Keeffe and Stieglitz fled each other in different ways. Stieglitz had a wandering eye, and he wanted it all -- he wanted O'Keeffe to be okay with his relationship with Norman, just as he had expected his wife to accept O'Keeffe. Maybe it was narcissism. He couldn't see how his actions would alienate others. She fled for New Mexico, I think, precisely for this reason. His simultaneous insensitivity and need for attention drained her. Even though she left, it was a tremendous struggle for her, for years thereafter, to work. She too had a breakdown, and it took quite some time for her to resume painting -- nearly ten years to make another abstraction.

CZ: O'Keeffe seemed to love NY and the exciting mix of people she found through Stieglitz's 291 gallery and his good offices. Yet finally, in order to do her work, she went to live in Santa Fe.

SN: O'Keeffe was very disciplined. Even in New York, I'm not sure she loved the party circuit. That's why the austerity of New Mexico appealed to her. At the same time though, there's a myth that O'Keeffe went out to the desert and found herself. In reality, it was very difficult for her to reinvent her art -- the letters reveal that. She ultimately made wonderful works in the southwest, but my personal favorites are the ones she made in the years before she moved out there. Her paintings from the 1920s reveal what a technician she was, especially as she became very fluent with oil during this period. The way she uses paint to create different light effects is magical. That took time and intense focus.

CZ: O'Keeffe began in pedagogy, and in the Arts and Crafts movement. Yet she seems to have landed far from these precepts later on. What was it about those two disciplines that resonated?

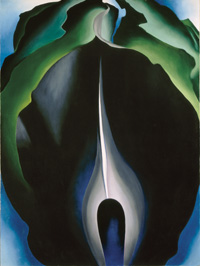

SN: Aesthetically, she landed far away from these precepts, but I don't think she strayed philosophically. The sinuous, organic forms of Arts and Crafts seem to capture the rapturous feeling of being immersed in the natural world. In many ways, O'Keeffe's rootedness in nature, her reverence for its forms and rhythms, expresses a similar sensibility. Likewise, you continue to see a didactic spirit in O'Keeffe's art -- particularly in many of the series we've included in the show, like the Jack in the Pulpit paintings, where she enacts a kind of case study in abstraction.

Georgia O'Keeffe -- Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV (1930)

Georgia O'Keeffe -- Jack-in-Pulpit Abstraction--No. 5 (1930)

Georgia O'Keeffe -- Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI (1930)

CZ: And finally: this summer there have been at least two other major O'Keeffe retrospectives, both in tandem with other artists who may have influenced her (Ansel Adams and Arthur Dove). Your exhibition shows how early an abstractionist she was, how much she marched to her own drum. Do you think she was influenced by the men around her or the other way around?

SN: Both. It's hard to imagine that influence in artistic circles is ever one directional. What makes O'Keeffe's work so singular is the degree to which she innovated through influence. Look at her abstract portraits of Paul Strand. It's almost impossible to think of a visual precedent, and yet she drew the idea of abstract portraiture from other modernists like Francis Picabia and Marius de Zayas.

Georgia O'Keeffe -- Untitled (Abstraction/Portrait of Paul Strand) (1917)

That's also true about O'Keeffe's relationship to photography. She learned from Strand and Stieglitz about cropping and magnification as visual techniques, and then applied those ideas to painting. I don't think any of her contemporaries did that. O'Keeffe has become such a celebrity that we think we know everything about her work, but the show holds many surprises.

THE WHITNEY TO PRESENT GEORGIA O'KEEFFE: ABSTRACTION September 17, 2009 - January 17, 2010. Following its Whitney debut, the show travels to The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., February 6 - May 9, 2010, and to the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, May 28 - September 12, 2010. A biopic on Lifetime Television appears this weekend.