The story you are about to read was found in my father's files. I heard him tell snippets of this story, but here it is from start to finish... unedited.

Hello. The story you are about to read is the personal observation and opinion of a Battalion HQ Company Commander and Battalion Adjutant of the 1st Bn., 16th Inf. Regiment., 1st Division, regarding the landing in Normandy 6 June 1944.

At that time the 1st Infantry Division was composed of:the 16th, 18th, and 26th Infantry Regiments; 2, 32, 33, 105 FA Battalions; 5th field, 155 FA Battalion (an aside: Battery D, 5th Field is the oldest continuous unit on active duty in the U.S. Army); 1st Eng Battalion; 1st Signal Co., ordinance and other support and attached elements.

The Infantry Regiment consisted of a Battalion HQ section. Battalion Sgt Major, Intelligence Sgt., Operations Sgt, Supply Sergeant, and clerk; comm. Station with a wire section which laid and maintained wire communications with rifle companies, radio section operations, radios in regiment net and battalion net, message center; ammo and pioneer platoon - ammo section supplied Rifle Company with ammo, pioneer platoon laid and picked up mines and any small construction jobs. AT (AntiTank) platoon with 2 sections of 57mm AT guns. Also a group of about 20 men who were limited duty who didn't want to leave.

In addition to being the Company Commanding Officer I was also Battalion Adjutant and took care of administration for the battalion

My name is Charles Hangsterfer, Colonel, U.S. Army (Ret). Civilian soldier. I was born 31 October 1918 in Philadelphia PA, the year of the influenza epidemic, and 11 days before Armistice of World War One. Halloween birthdays never allow for a birthday party - everybody is trick or treating and has no time for giving presents. Upon graduation from Gettysburg College I received a commission as 2nd Lt Infantry as a result of participation in the ROTC program. I went on active duty as a Thomason Act Officer in June 1940 and was detailed to Fort Benning Officer's Refresher Course and communications course. Upon completion I joined the 16th Infantry at Fort Jay NY. I never had a chance to become a "foot-soldier" as I was assigned to go on amphibious maneuvers with 3rd and 16th down in Puerto Rico. The army was short of supplies and equipment so we used row boats or made an outline of landing craft on the ground with rope, rocks, or whatever was available so as to get the boat teams used to acting as a unit. After the maneuver were completed, the 3rd and 16th sailed to Britain and acted as quartering party for the entire division to assemble at Fort Devens, Mass.

When Pearl Harbor was bombed, I was on detached service to share communications with the Navy, at N.O.B. observing ship to shore communications. Joint Operations are complex and even today from what I read of Grenada, it's still a problem for the Navy, Army, and Air Force to communicate with each other.

In June of 1942 I went with an advance party to Tidworth Barracks in England to quarter the division when it arrived overseas.

In November 1942 I landed at Arza, North Africa and participated in the campaign in Algeria as Regiment Communications Officer. When this campaign was completed we thought we were going home but instead landed at Gela Sicily. I was then 1st Battalion H Co. CO. As the song goes - "We won't come back till it's over over there." So the division went to England to prepare for the invasion of Europe.

Our training area was on the south of England in a town called Lyme Regis. A motion picture, The French Lieutenant's Woman, was filmed there. Outside of laying a fake cobblestone street the town hasn't changed for centuries. From Lyme Regis we made a practice landing on a beach in England called Slapton Sands. In the newspapers, Churchill was stating that in 100 days a second front would be opened. So our training was stepped up.

Every unit had to go through assault training near Ilfracombe, England. The rifle companies were divided into 30-man assault teams - consisting of pathfinder scouts to mark and blow a path through mine fields or barbed wire to mark way to a pillbox or strong point. They were supported by rifle, MG, and mortar fire, so as to maneuver a pole and satchel charge team who were to blow a hole in aperture of the pillbox. And then a flamethrower would finish off the job. It was a fire and maneuver plan which took time even when there was no hostile fire. A Russian General was observing our training and one of our staff officers asked the general how they did it in the Russian Army. He replied they keep rushing the area until the enemy runs out of ammo. I was happy I was in the U.S. Army when I heard this.

At the end of May the 100 days were nearly up and when we were told to load up. This time we were told to collect our laundry and pack up everything. Then we proceeded to the marshalling areas and were sealed in. A marshalling area consisted of Quonset huts and hard stands for our vehicle and enclosed with barbed wire and guards. (A soldier remarked he thought the island would sink under all the weight). We were crowded in a relatively small area which would have been a lucrative target for the Luftwaffe. Fortunately we never had an air raid.

In the marshalling area we were issued impregnated clothing as a protection against gas. The only good thing about this clothing was you didn't have to worry about B.O. and the aroma from the impregnated clothing was stifling. We were given some invasion money in French Francs so we knew we were going to France.

One day General Omar Bradley called a regiment officer's call and gave us a pep talk on the importance of our mission. I remember him saying he would give anything to be going in the assault waves with us. I was tempted when I shook hands with him at the conclusion of his talk to tell him I would sell him my place for 20 bucks.

About June 1st we were ordered to proceed to Weymouth and board our transport ship the "Samuel Chase." Once aboard the ship we were issued the operations order "Overlord." The big picture was - the British were to land on our left - our code name Sword and Gold Beach. The 4th Division was to land on our right at Utah Beach. The Rangers to land at Point du Hoc to our right, and the First Division and 29th were to land on Omaha Beach. General Clarence Herbert was the 1st Division CO and was in command of the initial assault on Omaha Beach.

The 16th Infantry and 116th and 29th were to be the task force and land first with General Norman Cata ADC 29th Operational Control. The 18th Infantry would follow the 16th, with the 26th Infantry following the 18th.

Onboard ship was a sand table which portrayed the terrain of the beach and area where we were to land. The 16th Infantry was to land on Fox Green beach with the 3rd, and on Easy Red with the 2nd Bn. The 1st Bn. of which I was a part was to land in back of the 2nd Battalion, pass thru this Bn., and seize high ground. A and C companies to lead with B in reserve and D in support. Since my company had a variety of jobs to do they were split up. My command responsibility was delegated to the platoon leaders. My Antitank platoon was on an LST (Landing Ship Tank) that would unload the amphibious 2½ ton truck (DUKW), it carried the 57mm AT guns, at a different time from the rest of the company. The bulk of my company was on the Samuel Chase less the AT platoon, ammo section, and kitchen personnel; and were to go ashore in LCVPs (Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel). Since I didn't have too much to do until we hit the beach I was given the job to call out the boat team numbers and have them proceed to the debarkation stations at the proper time. While aboard ship we practiced this procedure to make sure all boats were loaded on time. Going through the companion-way of a ship, especially with all the equipment the men carried, was slow going. The "Chase" was designed for amphibious landings - the LCVPs were loaded at deck level then lowered into the water through deck level thus eliminating climbing down the rope ladders or cargo nets. Even in practice, climbing down the side of a ship was a hazard. Someone always fell into the water, or if there were ocean swells, some got caught between the ship and the landing craft. A good many boat drills were carried out.... so when it was "for real" we would be ready.

Messages from President Roosevelt and Churchill and Eisenhower were given to me to be read over the loudspeaker system. I wasn't much good at reading out-loud, and fortunately John McVain, a radio announcer who was covering the landings for ABC Radio was on board to give an eyewitness account for the folks back home. I prevailed upon him to read these historic messages. My company thought it was me and congratulated me on what a great job I did - I never did tell them it was John McVain.

It was very disturbing to finally learn the landing was to take place in the daylight. The landings in Africa and Sicily were at night. I recall how naked I felt in Sicily when a searchlight picked up our landing craft. However, the navy knocked out the searchlight battery on the first salvo. However, our fears were somewhat allayed when we received the concept of the operation with all the support we were to have.

This is how it was suppose to go: The Air Force was to bomb the beaches, Navy gunfire was to bombard, and we had 100 self-propelled tanks in the water to provide initial artillery support. A special amphibious Engineer Group were to remove the obstacles and mines on the beach, and of course we were hardened, seasoned veterans trained, in which "No mission was too difficult, No sacrifice too great, Duty first. Nothing in heaven or hell could stop the Big Red One. So being the reserve Battalion, I thought all we have to do was to show our Big Red One and the enemy would run. Besides, it was Easy Red Beach, a good omen.

On the sand table and in photos it showed the obstacles the Engineers were to remove. They were utility poles planted in the sand on an angle with a mine attached to the front to blow up the landing craft, and railroad tracks welded together and placed on a concrete base to stop tanks. Since 1st battalion was to land after the 2nd battalion, I gave little thought to the obstacles. I thought whenever we landed, approximately 1 hour after H-Hour; it would be another day's outing at the sea shore.

On the evening of 4 June we were told D-Day was going to be on the 5th. The ship's mess consisted of steak and ice cream for dinner. Giving a condemned man his last good meal on earth ran through my mind. However, shortly after the evening meal, word came down there would be a delay of one day. I remember how let down everyone seemed. On one hand nobody wants to expose themselves to danger but this was main reason everyone was fighting... lets get it over so we all could go home. This would be another day away from home and another day of anxiety and sweating out what might happen.

To fill my spare time I read an account of the Marines landing somewhere in the South Pacific and what a miserable time they had landing in the daylight. To get my mind off that I got someone to play chess with me. For the evening meal on the 5th of June, we had a duplicate of the night before - steak and ice cream. Breakfast seemed like a couple of minutes after dinner.

I went to the battalion CO Quarters - Lt. Col. Ed Driscoll, for last minute instructions and to wish everyone luck, then went up to the loudspeaker on the ship's bridge to call the boat teams to proceed to the debarking stations. I enjoyed this detail because I recalled how uncomfortable it was, on the other invasions, waiting for my boat number to be called. Also I would be the last boat to be loaded and lowered into the water, which meant the rest of the group would be circling in the water, which often caused the troops to get seasick. Just as we had practiced, the boat teams got off in time. Then I said goodbye to the people on the bridge and proceeded to my LCVP. As far as I could see there were all types of ships, but it was surprisingly quiet.

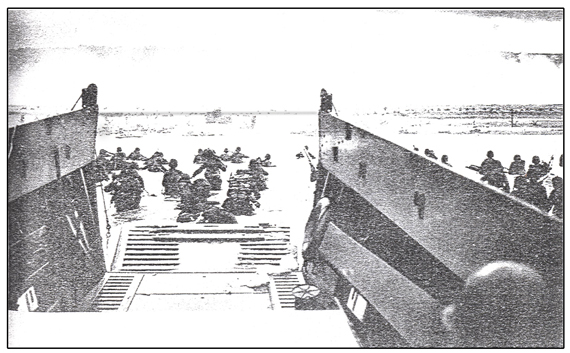

As we got in view of the shore, some of the landing craft from the first wave were returning to the transports. They waved to us, we waved back just like you would do on a pleasure boat ride. As we approached the beach I could see the water obstacles still in place. It appeared to be high tide so it was perilous trying to land. I could see landing craft being blown up by mines and could hear machine gun fire. I yelled to the coxswain to let down the ramp but Major Al Smith, battalion executive officer in front of the boat could hear machine gun rounds hitting the front of the craft and until it was all clear he didn't give the signal to lower the ramp. When the ramp was lowered the troops ran off in a hurry, but not before we were raked with machine gun fire which hit a few men. I helped one of them to shore and looked for Major Smith. There were so many troops on the beach it was difficult to find a space to take cover from the enemy small arms fire. There was one path through the barbed wire which led to what appeared to be a swamp. This swamp didn't show up on our photo so it must have been excess rain water. However, it was over waist deep so the troops had to hold their rifles overhead. It was just like a movie I had seen where some troops making a surprise attack through a swamp had done. I was concerned about a paper bag with an apple and orange I had taken at breakfast. It got wet and the orange fell out but I still had the apple.

When we got out of the water I stopped with Major Smith who had a small bottle of scotch. He gave me a drink and we shared my apple. He told me to go back to the beach and pick up anybody I could find from our battalion. When I got back on the beach I saw Bob Capa, a combat photographer for a magazine taking pictures of the carnage. He was behind one of the self-propelled tanks which had been knocked out. I found out later that only three of the 100 tanks ever made it to shore, the rest sunk. Also, somebody goofed up Capa's film when it was being developed...those moments are lost forever!

I found the Beach Master station and borrowed his loudspeaker to call for troops of the 1st Battalion to report to me. A few did report and they helped me round up more. I noticed a mortar crew getting set up to fire and I asked them if they had observation on what they were firing at. They didn't, so I told them to stop until our troops were up over the top of the ridge, besides, I was going up there myself in a few minutes and I didn't want to hit by friendly fire. Then an enemy mortar shell hit nearby me and I was pelted with stones, fortunately not a shell fragment, I so I was bruised. Later I found out that this beach was a source of supply for stones used to grind paint pigment.

I ran across a soldier yelling for the "pro" station. I had to find out where he found a woman so early in the morning and in the middle of all this enemy fire and confusion. He told me he had been screwed figuratively. He was unhappy that there had been no Air Force or Naval bomber shelling, and that mines had blow up his boat. So I told him to keep yelling for the "pro" station in hopes it would motivate people to move off the beach.

After I assembled a sizeable group of the Battalion I led them through the swamp back to Major Smith's position. Our Company A, Captain Jim Pence commanding, led his company across the beach and through the barbed wire and swamp and up the steep ridge. This made it possible for the group I was with to get off the beach. On the hill up the ridge was evidence of the price that was paid. Dead bodies either shot or blown up by personnel mines. It's hard to express the feeling I had when I saw the dead soldiers I knew. There wasn't anything there to help either; nothing with which to cover their bodies. I remember seeing them in training and at other occasions but you can't let it bother you too much because of other considerations.

When I reached the top of the ridge I got my first sight of hedge rows. The hedge rows were dirt mounds about 4 feet high and 3 to 4 feet wide which were boundary fences between fields. Difficult for tanks and vehicles, but afforded cover and concealment for personnel. In back of one of these hedge rows our Battalion Command Post was established. One of our attached groups - Naval Gun Fire Observer - reported to the Command Post and was looking for a fire mission. It was the first outgoing fire I heard all morning. However, it was of short duration because no more fire missions could be made unless observation of shots could be determined. Since there was limited visibility on account of the hedge rows our attached Navy fire support couldn't fire.

From our vantage point on the ridge we could see one U.S. Destroyer very close to shore firing directly at a pill box which had not been neutralized. After a few salvos the pillbox was knocked out of action.

It is difficult to put a timeframe on what happened on D-Day. First of all, if there were any, the pre-shelling and bombing had no effect on the enemy. The lack of this bombardment and heavy enemy fire made it impossible for the engineers to remove obstacles and mines from the beach, which slowed our movement. The special 100 amphibious tanks were a disaster. Of the few that reached shore, were quickly knocked out. Also, an additional enemy regiment was on maneuver behind Omaha Beach which allied intelligence didn't uncover. So instead of the 1st battalion landing on a secure beach, passing through the 2nd battalion and moving inland it was more confusion on the beach. Countless dead and wounded, wrecked landing craft, blown up tanks, enemy fire of all types. One thing I was thankful for was the lack of enemy aircraft.

The balance of the first day was spent in establishing our Command Post, establishing communication with regiment and rifle companies, and rounding up stragglers. The only enemy fire came from isolated snipers in the surrounding hedge rows. The special MP platoon silenced them so it was rather quite in our area. The enemy was concentrating their artillery fire on the beach and some of our artillery was now ashore returning the fire. The Battalion Motor Sergeant, while looking for a location for the Motor Pool, ran into about 60 Germans who surrendered to him and the prisoners were taken back to the beach. I found out later they were of great help taking care of our wounded and other jobs.

At nightfall, all the men that were to land were accounted for except for my Antitank Platoon. To my surprise they came walking into the Command Post, their "DUCK" amphibious trucks (aka. DUKW), which held the antitank guns, had sunk and these men were rescued by the Navy. The same thing happened to most of the tanks that were to land with us. Some of the tankers were trapped inside the tanks that sank. All around our position, we heard German machine gun pistols being fired, but none close to our Command Post behind the hedgerow. If you ever saw the motion picture, "The Longest Day," it had an excellent depiction of D-Day, June 6th, 1944.

On the 40th Anniversary of D-Day, I was at Slapton Sands and heard the story of a fisherman who had been having his nets fouled by an underwater obstacle. He sent a diver to find out why, and discovered it was a WWII tank. The fisherman bought the tank from the U.S. and had it salvaged. On the day I arrived at Slapton Sands the tank was repainted and on a concrete pedestal. There were crowds of people there to see the tank, when they found out I was an American Solider they talked with me and expressed their appreciation to me for the U.S. effort in WWII. It was gratifying, that after 40 years, someone appreciated and remembered our participation.

In civilian life you get dressed, eat breakfast, go to work, have lunch, work some more, go home, have dinner then relax and read, watch TV, listen to the radio, and finally go to bed. To compare a day in civilian life with D-Day: first, getting dressed - my uniform was chemically impregnated, I put on underwear, wool trousers, shirt, combat boots, field jacket, raincoat, along with 2 canteens of water, my pistol belt with pistol and ammo clips, and also a first aid packet. PLUS, a musset bag with cans of C-Rations, K-Rations, D-Rations, 2 changes of socks and underwear, cigarettes and candy bars, chewing gun, map case with maps, various types of documents, gas mask and steel helmet. After a breakfast of scrambled eggs, bacon and coffee, around 4 AM, I started my day. First I checked with the Battalion CO, and then I rode to work in a landing craft for a day on the beach, wading through a swamp, dodging enemy fire, climbing a hill, finding a safe place to work and sleep. After all this was done, I opened my canned food C-Rations, hash and biscuits, and coffee, the first I had eaten since my apple and breakfast. We had a few small Coleman stoves so I heated the hash and water for coffee. This was about 6 PM. Then I rested in a fox hole behind a hedge row trying to go to sleep

No one was there to ask if I "had a good day."

If they did my reply would have been yes - I was alive. Was I scared? I was always afraid and even more afraid to let my company know that I was scared. How scared was I? Several years after the war I had part of my intestines removed due to cancer. While having barium X-Ray the nurse commented to the doctor, "You can hardly tell that any of his intestines were removed." I told them that for nearly 3 years of my life, I kept my anus so tight that it probably stretched my intestines an extra 2 feet.

I once heard the statement, "It takes more courage to hide and go to Canada instead of serving in the Army or any of the services." I witnessed many acts of bravery and courage on D-Day. For example, a wire-man making several trips to the landing craft to get off equipment under fire and eventually being killed. The many dead who gave their lives blazing a trail up the steep slopes from the beach area are examples of true courage. After being in combat for over two years I considered myself a fugitive from the "law-of-averages" when I came out unscathed from the D-Day landing on Omaha Beach.

Colonel Charles M. Hangsterfer died at age 93 on March 10th 2012

I will be posting more "Stories from the Colonel" in upcoming blogs. Please check back!

Earlier on Huff/Post50: