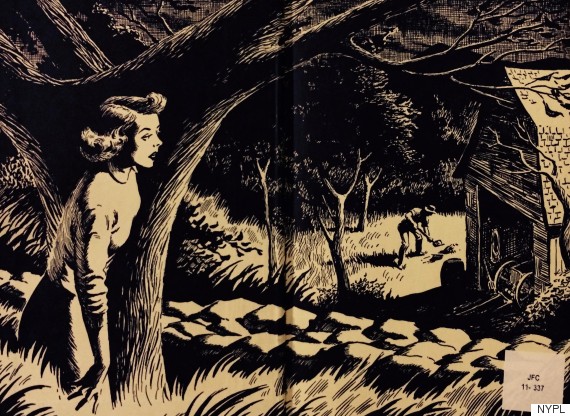

Illustration by Priscilla Frank

"Almost as many girls write to me as boys, and all say that they like to read boys’ books," Edward Stratemeyer, head of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, wrote in 1905. "But it's pretty hard to get a boy to read a girl's book, I think."

A couple decades later, Stratemeyer's network of freelance writers began churning out a hugely successful series of children's detective novels called The Hardy Boys, adding to the company's already impressively large collection of children's book titles.

Stratemeyer was a good businessman. Maybe girls liked reading boys' books, he thought, but perhaps they'd also like an adventurous heroine all their own. So, in 1930, he switched gears on his publishing machine and, with help from 24-year-old college grad Mildred Wirt, released the first three volumes in a new series about a girl sleuth named Nancy Drew. He provided an outline of the first three stories, and -- for $125 a pop -- Mildred gave them life.

That original heroine, though, is a far cry from the well-bred '50s-style debutante who appears in the ubiquitous yellow-spined volumes on bookstore shelves today. Back in the '30s, she was sarcastic, sometimes hot-headed. She carried a gun and drove a fabulous roadster with abandon -- not merely "as fast as the law allowed." She second-guessed herself, imperfect as anyone else, but could get herself out of dangerous scrapes alone, if need be.

Not far from Wirt, actually.

"Millie always thought she could do anything that she wanted to do," Nancy Drew collector Jennifer Fisher told The Huffington Post. Wirt's small-town Iowa childhood allowed her freedom for outdoor exploration. She wasn't one for girlish dolls, Melanie Rehak writes in the Nancy Drew history Girl Sleuth, preferring instead to borrow books from neighboring boys. After graduating from a high school class of four, she got her master's degree in journalism from the University of Iowa (the first woman to do so) and used it to find a full-time job. The Nancy Drew ghostwriting -- with emphasis on ghost, as she was under strict orders not to reveal herself as the real "Carolyn Keene" -- she did on the side.

Those first Nancy Drew volumes slid off the press easily. Then Edward Stratemeyer died. He'd intended for his daughters, Harriet Adams and Edna Squier, to sell the syndicate -- worth about $500 million, Rehak writes -- but hadn't counted on the market crash in '29. In his defense, though, few had. So the women packed up their father's papers and moved the Stratemeyer Syndicate from Manhattan to their home in New Jersey. Luckily, Harriet, a Wellesley grad with opinions to spare, had already been helping edit manuscripts in spite of her traditionalist father's discouragement. He allowed her to work in the privacy of her home, where classy ladies belonged, of course. Soon the syndicate was whirring along.

The well-to-do sisters shipped off new outlines in return for manuscripts and sent edited versions to print, beginning the publication cycle anew. They introduced new characters like kindhearted Bess and boyish George, the cousins who help make up the series' crime-fighting Three Musketeers in book #5. Then there's Ned Nickerson, Nancy's almost totally platonic boyfriend, who shows up in #7 "as a filler" under Edna Squier's request, Rehak notes. Notably, Nancy began to feel Adams' influence, becoming a more polished and polite young lady as the series progressed.

Wirt dipped out of the series for a bit after a pay cut, eventually returning to write through book #25. By day, she worked as a newspaper journalist; by night, she typed up children's lit at her sick husband's bedside. His death in 1947 was hard on her, Fisher explained, and she stopped writing about the girl sleuth soon after.

But as Wirt drifted away from Nancy Drew, Adams became increasingly attached. Sales began to slump in the '50s, Rehak noted, and the books were feeling a bit dated. Publisher Grosset and Dunlap wanted them shorter, too -- 20 chapters at 180 pages instead of 25 chapters with around 210 pages. And the books' old-fashioned stereotypes, about black and Jewish people in particular, needed to be worked out of the text.

Adams took out her editing pen and, from 1959 to well into the 1970s, she helped revise the first 34 books. She and a team of in-house writers rewrote some completely, while others just got a touchup. Nevertheless, the process of trimming and scrubbing left a more demure, good-girl detective. The differences prompted Phil Zuckerman, founder of the small Boston reprint house Applewood Books, to set about obtaining rights to the original Nancy Drews and Hardy Boys in the early '90s. He'd barely recognized the contemporary Hardy Boys -- also extensively revised -- as he read new copies to his sons.

Those reissued Applewood editions are now out of print again, although they're easy to find online.

At the end of the day, the syndicate's series were never masterful works of literature. But as readers of the originals can attest, Original Nancy was a "little more rough and tumble," Fisher said, compared with cool, strait-laced Revised Nancy. She became an 18-year-old with a blue convertible instead of a 16-year-old with a blue roadster. Revised Nancy played by the rules. Sigh.

Some differences, of course, were necessary.

It was Edward Stratemeyer who requested minority characters be written in dialect, Fisher told HuffPost. Wirt's husband would help her -- she wasn't so great at imagining how the black housekeeper in The Hidden Staircase, for example, might speak. Or rather, might speak if the housekeeper were actually nothing but a "positively vicious," "surly-looking creature" as she's described. A sampling:

"I suah thought I heard somethin'! An' it was right down in this heah basement, too! I done reckons my old ears is playin' me false. I hears noises dat sounds like dey was in de basement and dey was only in my haid."

"You carries on like a fool with all yo' squawkin' and yo' speechifyin'!"

"You git, white man!"

The worst of it, Fisher noted, only appeared in the first handful of volumes. Book #1 shows us a black villain laden with stereotypes: a man who drank too much and "shuffled" around. But instead of facing the original books' problems, Adams avoided it altogether, simply eliminating offensive characters and turning Nancy Drew's universe into a less and less diverse place revised book by revised book. Which is another kind of disappointment altogether.

"I was really concerned that somehow by reissuing [the original Nancy Drew books], you know, the company and myself and everybody involved would be seen as racist," Zuckerman said to HuffPost. But for Zuckerman, their inherent cultural value, allowing readers "to understand where we come from, and to also measure how far we've come," outweighed his fear.

Other changes took away our heroine's independent spirit.*

In newer editions, Fisher and others have noticed how Nancy increasingly finds herself needing help from her boyfriend, Ned. Which is fine -- everyone needs an extra hand sometimes, right? -- except that originally, she didn't. Nancy didn't even need her friend Helen Corning in the original Hidden Staircase mystery. She found the stairs' trapdoor, she found her missing father, and she pieced the whole mess together alone.

"Nancy doesn't quite lose all of her gumption that she had in the '30s," Fisher told HuffPost, "but she becomes more toned down, and relies on others instead of just herself."

Other small details, such as losing a pump in the river muck after narrowly dodging a runaway truck with her father, who helps pull it out, show her to be a less self-sufficient young woman. Traditional morals seep into the series, too, when Helen Corning gets engaged -- the originals were not nearly as concerned with marriage. To be clear, Nancy still solves the mysteries and saves the day in both versions. We're just sad to see her lose a bit of that independent ability we love about her, in the name of chivalry or politeness.

*And her guns. All mention of those -- given to her for protection in the original series, "just in case" -- were scrubbed. According to Zuckerman, Harriet and company started to feel more responsible for their content and the lingering effect it may have on young readers.

Ultimately, her feisty comebacks faded away.

Original Nancy replied "icily." She "retorted hotly," "demanded sharply," "cried angrily," and "snapped," unable to keep her temper "in check." She does all of this when a strange man barges into the Drew household accusing Carson Drew, Nancy's father, of dishonesty in The Hidden Staircase.

Revised Nancy is cool as a cucumber, barely ruffled. In the same scene, she speaks "evenly," "replies," "asks," and "frowns" when displeased at the man's suggestion, which he delivers seated calmly on the couch -- not on his feet and nearly getting into a physical fight with Ms. Drew. These edits rob us of the more richly descriptive dialogue that gave Nancy her spunk.

In the revised editions, Nancy is a far less opinionated woman, too.

Maybe that's opinionated bordering on "judgmental" -- but whatever. In The Secret Of The Old Clock, Fisher notes, Nancy makes some snarky remarks on the Topham sisters, presumed heirs of a recently deceased man's fortune. Calling them "vapid creatures," she remarks, "It would be a shame if all that money went to the Tophams! They will fly higher than ever!" When it comes time for them to learn they're not in the will, Nancy would "give a lot to see how they take it."

Revised Nancy is less vindictive. The Drew's housekeeper makes disparaging remarks against the Tophams instead, and the sleuth merely asks to be present at the will reading in the revision. But she doesn't seem to take praise as easily as the more confident Original Nancy, Fisher writes, and lacks a certain gutsiness -- Nancy is given the old clock in the new version, and asks for it in the old one.

She's also prettier in the revised editions, but not too pretty.

Rehak explained how Adams took issue with the newer illustrations of Ms. Drew -- she was too curvy, or her lips weren't right. She absolutely could not be "sexy." That said, for a girl who prefers being "interesting" to "pretty," Nancy sure smiles a whole lot more during her sleuthing in the editions that kids are reading nowadays. Her eyes twinkle and sparkle and do other glittery things. For seemingly no reason whatsoever, she switches from blonde to titian-haired. The original books mention she's an attractive girl, sure, but in the revised editions we're not allowed to forget it.

Mildred Wirt does a swan dive.

Still, in all of its iterations over the years, the Nancy Drew series has inspired a long line of admirable women -- including the Notorious RBG. Plenty of us grew up watching Nancy puzzle her way through mysteries, elude the bad guys and, yes, sometimes help Ned or her father out of a scrape. The series continued on after Adams' death in 1982, numbering at 175 volumes when it finally ended in 2003.

For her part, Wirt (later Mildred Wirt Benson) lived a long and badass life. She wrote about 120 children's books in total, got her pilot's license at age 59, and started writing a column about it for the Toledo paper she worked at for nearly 60 years.

It would have been nice to see more Original Nancy, absent the casual racism, in the revised books that have found a place on so many young readers' shelves. She represented more fully the kind of heroine that young girls sought by reading boys' books, as an observant Edward Stratemeyer noticed over a century ago. But the details that painted her headstrong and bold have mostly been lost to the archives.

Correction: The author of this post will forever confuse the Canadian city of Toronto with the American city of Toledo, and feels bad about it. Mildred Wirt Benson worked for a Toledo paper, not a Toronto one.