This is the final installment in a four-part series. Read the third here.

Nanga Parbat, the Killer Mountain, Pakistan

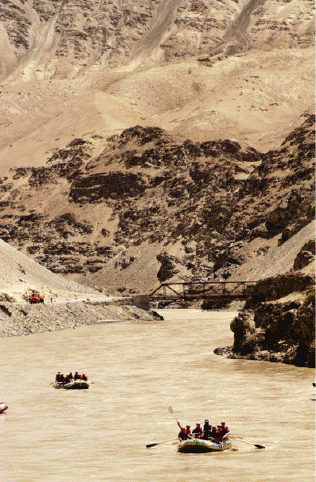

After a few more bends in the river, another curious sight appears: a sign held high by a

Pakistani in Western attire: "Pakistani TV welcomes the Americans." Khalid Zaida, a television

producer from Rawalpindi, heard about our little expeditions and, eager to capture on video the

inside story, wants to ride along down the river. After his inspired welcoming, it is hard to deny

his wishes, and we receive him onboard to shoot the rapids with his brand new camera.

Late in the afternoon of his second day on the river, Khalid sits with me in the bow

as John Yost rows. This is a rascal of the river, and a slight miscalculation puts

the boat in the wrong place at the wrong time. It drops into a huge hole, and flips.

It is dark and cold and typhoon-like underwater, but Yost and I have capsized on six of the seven

continents, so the feeling is not of panic, but rather purpose. We pop back into the light, gulp for

air, then grab the overturned raft and pull it to shore. But looking about, Khalid Zaida is missing.

We race down the stony bank, and with relief we find Khalid floundering in an eddy below the

next rapid.

But as we pull him in he says he is blind. He confesses that he can't swim, but figured that since

we were Americans, we were infallible in our navigation. He describes the experience, saying

he was sucked to the river's bottom and spun violently; he lost consciousness, lack of oxygen he

thinks. When he surfaced he was awake, but he couldn't see. After a few tense minutes, his sight

fades back in. On inspection it seems he burst an eardrum, but for him the worst loss is his $1800

camera, for which he had saved three years.

The continued savagery of the Lion River is wearing us down. Then we hear rumors from

soldiers along the shore of a monster rapid downstream called Malupah. We decide to park, claw

up to the road and flag a jeep to scout this myth.

It turns out the river is very much navigable to the entrance of Malupah, and so quiet is the

gateway that an unwitting boater, or swimmer, could easily be swept in. But once in, it is a circle

of hell Dante didn't know about, a liquid inferno without escape. A granite wall, the size of El

Capitan, blocks the direct flow of the river, so twisting and turning to find a way out, the Indus

has cut a fissure barely a boat's width, and hurls an angry, fuming torrent 25 feet to a trough

below. No living thing carried into this abyss could survive Malupah.

And it is a portage that could take days. So we decide to employ the jeep to scout further

downstream, as far as the Gilgit confluence, passing all too frequently small stone monuments to

victims who had plummeted off these cliffs. I become nauseated, not so much for the roughness

of the ride, but from the constant reminder of how near death is along this seam of Pakistan.

As

we lumber down river it is apparent the rapids are getting worse, not better. The gorge becomes

narrower. In some stretches there is no level shoreline at all, so impossible to portage. There are

more and more waterfalls. The Indus here is un-runnable; impossible.

It is time to concede. The two rafts float down to just above Malupah, where we hire a transport

truck painted like the walls of a cheap disco. We load up and leave behind Malupah and the maw

of the Lion River.

It is 30 miles to the confluence of the Gilgit, where we once again launch the rafts on the waters

that hosted the Hatches back in 1956. Both Bus and his son Don have passed, but we raise a cup

of Indus water to them. It is clearly a terrific location for a widescreen movie. High above the

blue foothills, almost floating in the sky, Nanga Parbat looks too beautiful, too detached, too

innocent to deserve its Western nickname, The Killer Mountain. It seems an emblem of purity,

dignity, repose, a white vision in a gauze-like haze of blue. To the mountaineers who have

grappled with it, however, it deserves its handle. It claims more deaths per attempt than any other

major mountain in the world.

As the river swerves closer to the mountain, Nanga Parbat reveals it structure more clearly;

rather than a single peak, it is an enormous mass of rock ascending in successive ridges and cliffs

to culminate in an icy crest. No other peak within a radius of 50 miles reaches to within 10,000'

of its 26,660-foot summit.

At the last camp on the Indus, within a few miles of the Rakhiot Bridge take-out, a local villager

steps out of a cave in twilight. Dressed in the ragged clothes of the mountain native, he quietly

tells tales of the mountain looming over us. It is protected by spirits of uncertain temper; its

snowy peaks are inhabited by fairies, and when the sun shines hotly, the smoke at the mountain's

crest is that of djinns cooking their bread. He speaks of demons, of giant frogs whose croaking

shakes the snows, of snakes a hundred feet long hidden in the glaciers. He then takes his leave,

and disappears into the darkness of his cave.

Just shy of the Rakhiot Bridge, where Jimmy Parker's name is inscribed with those of the

climbers lost on Nanga Parbat, the canyon squeezes together and presents a series of three rapids,

all of jaw-breaking difficulty. Neither Hatch nor any of his party left a detailed description of

where the fatal accident occurred, but we agree it was likely here. After more than three weeks

on the Indus, with superstition in the air, a quick vote ends the expedition at this spot, at the

head of the final gorge. Pakistan's Lion River proved its purpose was to take waters from the

roof of the world to the sea, and men of reason were not necessarily invited along for the ride.