To see 7 Rings, An Artist's Game of Telephone from the beginning, please click here.

Today, Silvana Straw responds to Jared Pankin.

Outerspace

After my grandfather's funeral,

we drove the four hours

from Marysville back to New York,

my Dad and I blasting the stereo,

and singing Elton John songs

at the top of our lungs.Night fell and we grew quiet,

as the red moon revealed herself above the mountain,

full of love and promise that it all makes sense.Everything that day felt like we were in outer space...

it was all so sad and it was all so funny--

the funeral home, the cemetery--

Great Aunt Sally's stories of Grandpa

eating her out of house and home...and then onto the giant crater of Manhattan,

magnificent and still,

the new Trump buildings lit up like electric beehives,

one less light in the window.Falling asleep in my little sister's bed

with her window to the world,

I felt as though a thousand years had gone by--

as though I had crawled on my knees

to the center of the earth and back again,

and still knew nothing.

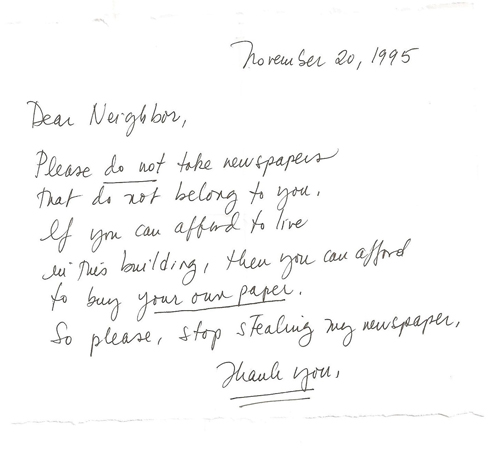

Dear Neighbor Part I

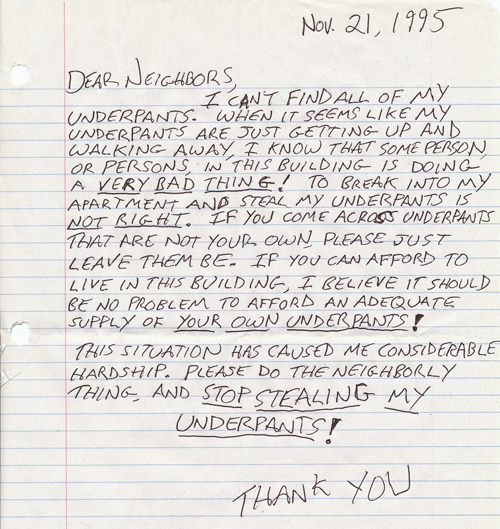

Dear Neighbor Part II

Dear Neighbor: Text/images from a video collaboration between Silvana Straw and Scott Wingo. They stumbled across the first letter from a neighbor one day taped to the wall in the hallway of Straw's apartment building. The second letter is Wingo's response -- which he in turn taped to the wall in the hallway next to the original letter.

Silvana Straw is a poet, writer, performer and D.C.'s original Poetry Slam Champion. Her solo performances have been commissioned by The Washington Performing Arts Society and Dance Place. She has performed in venues throughout the U.S. including: GALA Hispanic Theatre and The Kennedy Center (Washington, DC); Galleria de la Raza (San Francisco); The Nuyorican Poets Café (NY); Out North Theatre (Anchorage); and The Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has appeared in publications such as Indiana Review and Conversations Across Borders. Earlier versions of Teratophobia have appeared on Gargoyle #52 and in the Short Fuse Anthology. For more information, click here: http://limpflig.blogspot.com/

Tomorrow, Rebecca Campbell begins to wrap up of this incarnation of 7 Rings: An Artist's Game of Telephone.

![]()

Today, Jared Pankin responds to Steve Tuttle's "The Scold."

It is true I don't like babies. I never wanted them; I don't think their cute and I can't stand their noise. For that matter I don't like kids, I don't like teens and I don't trust anyone under the age of 46. I can't even believe that people even want kids. What a crappy world to bring a crying baby into. Yes, I am assuming I was one too. I've seen pictures but babies all look the same to me. It doesn't matter. I never asked to be born; that I know of. I know people keep having them nonetheless. It is beyond my reach of understanding, why people want to have kids. I have friends that had one kid, life was getting better and then they decided to have another. But life tricked them and they had twins. Just as they were adapting and getting used to three, an "accident" happened and they are having their fourth. What the fuck were they thinking? Because the wife was near forty and had twins that her eggs had dried up. Bullshit. The husband called the other day and went on a rant about healthcare, The President, etc. I should preface that after their twins were born they opted out of any pre-natal healthcare thinking that they were done with birthing babies. But when that was not to be and they couldn't get back the care, that's when my friend called and wanted to sell a bunch of their crap to pay for the birth of their new baby. My friend likes guns and shooting them, and I have been shooting with him. We can step out our back door and shoot things. My dogs can bark at three in the morning and I can play my guitar and sing as loud as I want anytime I want.

I here my friends kids cry, and laugh, and shout. I here him shoot his guns when I am not with him. I barely notice, except that I know they are his kids and his guns and his chain saw and his tractor. I hate the city because we are packed in like five pounds of shit in a two-pound bag. Last time I brought my dogs to Los Angeles and stayed at my house, the neighbors complained about a barking dog at two in the afternoon. I have also had complaints from another neighbor with a baby about a barking dog and her kid needing sleep. My dogs needed to bark.

My point is, everyone is crazy and there is no solution.

Sincerely,

Jared Pankin

p.s. Don't blame me for my dogs barking and I won't bitch about your crying kid.

Steve Tuttle responds to Julia Schwartz's paintings.

The Scold1

She's standing there in the doorway, just standing there. And we have to wonder why she's standing there like that, like someone who sees a doorway not as a thing to pass through, but as a thing to stand in, making a point by not passing through, refusing to pass through. Why is she standing there in our doorway - it is ours - and not passing through and not going away and not saying more than she is saying? What does she want? Because she must want something? Standing there in the doorway like that must mean something. But it's hard to say.2

She has asked us to please consider others, to be considerate of others who might be nearby, who might live on the other sides of these walls so thin they will hardly support a nail, these walls so thin they will hardly contain the heat we all pay too much for.3

Are we inconsiderate people? Are ours the actions of people who fail to consider others? This look that passes between us, this look that hangs in the air like our frozen breath, this look says that we do not think we are the people she thinks we are. This looks says that one of us should say to the woman that we are not the culprits if culprits are what she's after. This look is content to assume the passive voice and say that perhaps a mistake has been made.4

The baby, she says, the baby. And we say, the baby? And she says that it would take so little, really, a little consideration is all she asks. All she asks, she says, standing there in the doorway that is very clearly ours and not hers is that perhaps we might consider others a bit more than we have. And here she raises up just a little, pushes forward onto the balls of her feet, stretches her neck like she's a bird. She leans through the doorway that is ours and not hers, peers into the space that is ours and not hers, looking for the baby, the baby, that sweet, sweet, inconsiderate baby.5

We are not inconsiderate people. We are not, of course, unaware of these thin walls that will do so little to muffle sounds meant for other ears. And we have wished - haven't we - for walls just a bit thicker than these. But the baby? The baby is a baby. The baby has been a perfect baby, an ideal baby, a model baby. The baby has performed babiness with such perfection, such total perfection.6

We have not slept well, it is true. And we have smiled our thin smiles and said to each other that one day, soon enough, we might refer back to this exhaustion like the others have done (have claimed to have done). And there have already been moments we regret, moments in which we have said oh, hell, or dammit, or when we sighed so heavily it was as though we had cursed our god or the graves of our grandmothers. There have been these moments - these moments that are ours, that belong to us and us alone - that are no business of this woman whose head, like a periscope, keeps searching for the inconsiderate baby.7

We have not told her she can't come through the doorway. We have not told her she can. We opened the door, as considerate people would. We said hello and smiled, as considerate people do. We allowed our brows to wrinkle, our faces to assume expressions of consternation, as any considerate people must, when she said that there was something the matter, something in need of correction. Our heads bobbed up and down while she talked, in a continuous state of agreement. Our heads said everything there was to say: that we are considerate people who will listen to the pleas of a hunched, old woman, who will wait patiently through her senseless preamble, who will speak in hushed tones when hushed tones are appropriate.8

But, the baby? The perfect baby? The sweet baby that is ours and not hers? There has been crying, certainly. Oh, how our sweet, perfect baby cries when crying is necessary, when crying is the perfect, sweet, appropriate thing for a baby to do. Oh, how our baby cries when a baby ought to cry, when a baby must cry, when a baby would be mistaken not to cry. All that crying, all that crying, oh sweet baby, the crying you can do. But it's part of the equation, isn't it? Isn't there an equation somewhere that always ends with crying, that must end with crying? Isn't crying at the end of that equation and others, too. Weren't we told to brace ourselves for this? Weren't we?9

She cranes her neck, clearly dissatisfied. She allows her weight, the little there is of it, to fall back to where it belongs, on her side of the doorway, the side that is not ours, the side that is also not exactly hers. Her face has this thing about it, this fixity. Her face is so perfectly unchanging. Her eyes are wide open but seem so flat and sleepy. Her lips are thin and form a perfectly straight line that looks as though it has never smiled. Her face is perfect and awful. Her face is perfect and mean. Her face is ready, at any moment, to assume a scowl, to glower.10

May I? she says, and uses her hands to make a motion that suggests she is giving us something. She turns her palms toward us and opens her arms as though to escort herself into the room. No, we say, no she may not. And that does the trick. That puts a little curve in her perfectly straight, perfectly flat, perfectly vile little mouth. And then we apologize, make our own gestures - palms to the chest as though clutching our own hearts - and say, the baby, the poor, sweet thing. The baby, we say, and we shake our heads and purse our lips let our hands come together like an empty cup before us to show exactly how sorry we are. The baby, we say. Finally getting some sleep, we say. Thank the heavens, we say.11

The baby, she says, we must consider the baby. The horizon of her mouth has found its equilibrium. Absolutely, we say. We can hardly tell you how happy we are that the baby is finally getting some sleep, we say. Yes, she says, we must consider the baby.12

She is on the other side of the door, the side that is not ours. She is in the hallway. She is in the hallway that is not ours and not hers. She has every right to stand there in the hallway. She has every right. We thank her for nothing in particular. We whisper good night as though we just remembered to keep our voices very low, as though we have developed, of a sudden, some pressing need for stealth. We give the door a nudge, a quiet little nudge, and let it close gently, quietly, as though of its own accord.

Today Julia Schwartz responds to Anna Abelo's recurring dream.

Anna Abelo responds to Laura Ross-Paul's paintings.

I have a recurring dream. In this dream I am a writer trying to write the perfect lesbian film.

I type and type but nothing seems to make sense.

Should I write about the past?

My first love?

My first cat?

My first feminist book club?

My first bar fight?

It's been 20 years now and all I have are questions and more questions.

What type of Lesbian am I?

Am I the right type of lesbian?

Why did I get all those strange haircuts?

The more I search for answers, the more I feel like something is searching for me, but what?

Suddenly, she reveals herself. A lady in an owl mask. I think to myself, "Is that my Mom?"

As I unmask my predator I realize what's been following me is me, but older...

Laura Ross-Paul responds to Rebecca Lindenberg's "Questions About Beauty."

Rebecca Lindenberg responds to Rebecca Campbell 's "For Fever Babies."

Questions About Beauty

How wind finishes

wood into bone socket,

breath-only intoning over

and over it. How

summer's fevered mind

gathers spool and frond

into nests lovely as they are

curious - I have

so many questions

about beauty. How black

shimmers in a wing,

why crickets remember light

in their shrill purr,

how unstill is any given leaf,

how many words there aren't

for the idea of green. Why

does beauty elicit longing,

for what god? What if

splendor's not in things but

transformations? The same

wind tarnishing a trunk,

thin reeds can capture into song.

Chrysalis, snakeskin, bay

wreath, splendid remnants

of change not wrought,

just witnessed. Attention

into ecstasy, feather

into moonrise, stem

into instrument and branch

into artifact, itself, again.

Rebecca Campbell responds to Jennifer Colville's "Tonight, the Moon Is a Bullet Hole."

Rebecca Campbell, For Fever Babies, 2010, Juniper burl, piano hammer, butterfly wing, copper bee, cotton string dyed with blood, 5" x 3 ½".

Jennifer Colville responds to Christopher Colville's "Harvest."

Tonight, the Moon Is a Bullet HoleWe're driving up over the bridge, to the edge of the world, or, at least, to the edge of our crinkly old map. We're driving into a foreign city that is really just a jumble of islands rising up to meet us as we crest their bridges, and I am thankful, at this moment, that my husband made me take the extra-strength drug.

It's a dark dark night and the moon is a bullet hole, shot through a construction paper sky. In fact everything in downtown Vancouver seems cut out of an elaborate stencil - the white orbs and tubes of the street lights, the grids of lit windows checkering the sides of the hundreds of identical sky scrapers. It's a set design of a city, perfect for a film about the future.

Our two-year-old son is passed out in the back. Buckled into his high tech car seat, he looks like a mini astronaut, from whom ground control has asked too much. We have blasted him through space, for five days. We have driven him up the side of an entire continent, crept along steep cliffs, and wound through prehistorically tall trees. We have frolicked with him in icy cold brooks and camped, covering ourselves with thin sheets of plastic. And now, "surprise!" We are sick.

My son got the virus yesterday, and it's moving through him with intensity, flushing his cheeks, pushing tiny beads of perspiration onto his forehead. Asleep now, he's never looked more angelic, more doll like, and I'm reminded of Victorian photographs of dead children, black and whites, where the pink has been rubbed onto their cheeks in perfectly round orbs.

"I read in my book that high fevers can cause seizures," I tell my husband. There is tension; there is obstinance in my voice.

"They have to be really high," he says, "I'm not worried,"

But I think he is cavalier. He's an M.D., and he's driving too fast, and I'm still angry with him for insinuating that I was paranoid when I sensed our son was getting sick. Angry with him now when he says, "I'm more worried about you."

How has he become so good at spotting the onset of my mood gathering? This turning inward, the gathering up of everything into black and white, into me against him.

Still, I gather, gather, gather. Because I want to stay here, in this city for the night, and I imagine he wants to take the ferry to the tiny island, to search for a cabin in the wilderness. I imagine he wants us to reach our planned destination. Our finish line, all so we can take a picture and tell a good story. But I am done. I am tired of his "wilderness," and believe only a tyrant (his profile is illuminated in a sharp silhouette against the window) would ask me to do this now.

We have done our nature duty, I will tell him. We have been humbled by the wind and rain. We've been tiny blips against sublime landscapes. We do not need to completely disappear.

He will say, "It's not us, it's nature that's rapidly vanishing, we must see more!" and I will say, "If that is the premise, shouldn't we practice living without it? Shouldn't we practice sleeping in a city of the future, such as this one?" I will tell him, condescendingly, that his distinction between nature and civilization is partly artificial, that if he wants a wilderness, he should just look at me - at my hair, which has thickened and risen yeti-like around my head, and at my canines, sharper than I remember when I run my tongue over them. For I feel all the wildness of a grizzly rising inside me, when I imagine having to take my fevered boy over another body of water, into a cabin in the woods.

But as it went, something else happened, the medicine, the strong drug he made me take kicked in. Or, maybe I'm finally maturing. Maybe my wildness is vanishing too.

I simply say, "I'd like to stay in a hotel tonight."

And he says, "I was thinking the same thing."

Christopher Colville responds to Nicole Walker's "Germination."

Today, Nicole Walker responds to Jacob Rhodes' "Everything Is Gathering."

Germination

I went to the cellar for the seeds. We thought we'd saved enough. I'd collected seeds from the Hopi. My husband had kept several heritage varietals from his uncle. Sometimes, when we were bored and prescient, we ate our tomatoes, spit the seeds in our hands and dried them on the window sill like so many wishbones from Thanksgiving. We even saved Monsanto seeds--they said they wouldn't grow again without their double-taxed permission but who believes in that many mechanical genes clicking around inside a miniscule seeds like microscopic figures from Tron? It's not a matter of whether we believe or don't believe. We're out of seeds and, even if we had seeds, the rains that the weatherman promised are coming not from the sky but from the ground--great big bubbles of trouble--hot and shooting, like geysers or other unseemly projectiles. Still. We can't over worry. Perhaps within the ground-cracking hot waters there's a new seed or a new food or a new light. It's dark and cold and we're a little hungry but there is always tomorrow. The wishbone said so. The trees that have left their sticky shadow-pasts on the window sill so argue.