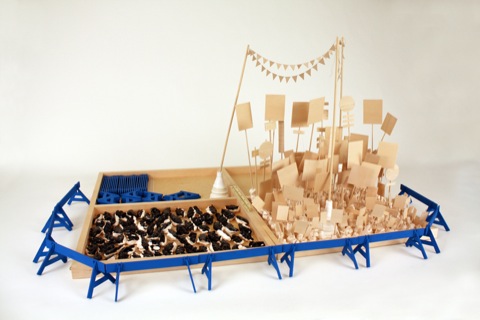

Andrew Cornell Robinson,Disobedience, 2011, Ceramic, wood, paper, string, enamel, 27 3/4 x 61 1/2 x 49 1/2 inches (variable), courtesy of Anna Kustera Gallery

No matter your political beliefs or aesthetic inclinations, the most intriguing exhibit in Chelsea this season has been Andrew Cornell Robinson and Gregory Green at Anna Kustera on 21st, closing this Friday December 23rd. The seduction is largely topical, opportunistically so, in that this appears to be the only exhibit in a Chelsea gallery that explicitly engages with the content of Occupy Wall Street. From the street and through the window is Andrew Cornell Robinson's Disobedience, a game board depicting what appears to be the pieces for a Zuccotti Park, and inside is Gregory Green's Through the Night Softly, tire spikes across the gallery floor. Yet for each of these artists addressing Occupy Wall Street was not the originally intended purpose of their work, conceived as it was before September 17th. Even so, selected by Anna Kustera for their seeming prescience, Andrew Cornell Robinson and Gregory Green differently express political imaginations clearly enervated by present conditions. What follows below are interview excerpts with each of the artists.

Catherine Spaeth: I knew nothing of your work until I walked by the gallery window and saw Disobedience, it was the only thing going on that seemed to be addressing what is happening at the moment, so I thought, but when I spoke to Anna Kustera apparently this was conceived and made before any stirrings of Occupy Wall Street.

Andrew Cornell Robinson: Yeah there's a bit of synchronicity there, and Anna thought the same thing, she thought I was making work about the Occupy Wall Street protests. In actuality I wasn't; but I was addressing issues of power, class and rebellion. It was really coming from a different place, it wasn't reacting to specific political stuff necessarily, but in a roundabout way the work is an examination of power. Let me explain.

In the past few years my work has really changed. I would make artwork intuitively and then in retrospect try to derive meaning from the work. And while that still is part of the process, about three years ago I started to incorporate a technique that is used by designers and advertisers, which called for the creation of personas. Marketers use personas or fictional characters that represent customers they want to sell stuff to. They tell stories about them and then tell designers to make a product or a campaign for their target audience. I knew this because I'd done a lot of freelance work in that world and I thought it would be interesting to make a persona not based on a target audience but as a means to explore a historical character or a particular feeling. For example I ask questions, such as what does a persona want? What kind of things do they need or desire? What is their life like? What objects do they surround them selves with? What are their stories? What are their shortcomings? Using the persona at the beginning, gives me fertile ground to make art from. So the work "Disobedience I" is not a direct response to Occupy Wall Street, because I began that work before the occupations began. But it taps into a larger feeling in the air these days. A sense of rebellion.

The desire to explore rebellion began as conversation between my partner and I. We were talking about identity, and whose stories get told and whose fade away. Stories about history, characters, family and people, and in particular rebels. My partner is from the Dominican Republic and he told me a story about his maternal grandmother and an aunt who were both in the underground fighting against the fascist dictator Trujillo. I was fascinated to learn about the rebels in his family tree partly because both of our families have weird connections to revolution. I grew up here in the U.S. and my family has ties to the Revolutionary War through ancestors who fought at the battle of Brooklyn and Trenton. In both cases these rebellious relatives nearly lost everything before they began to fight and both became victorious in the end. So from a conversation about the misadventures of dead ancestors I started writing personas about two revolutionaries, and then began making ceramic and sculptural objects, costumes and images. These were gathered together in an exhibition that was installed as a fake historical society in Brooklyn. Creating heirlooms, objects, weapons, photo-essays, around these two revolutionaries, well it was really quite funny. Making the work for and about another has enabled me to explore some new ideas; ideas that are both social as well as deeply personal, but without being embarrassingly confessional.

So the work in "Disobedience" on exhibit at the Ann Kustera Gallery is something new, but created in a similar manner as the work I just mentioned. I was reading Erich Fromm's essay "On Disobedience" and thinking about what it means to transgress personally and socially. This new body of work begins with a fictionalized persona based on Jean Marat, the French Revolutionary. I wonder what would Marat be like today? What would Marat do? What kind of situations would he be in? The real Jean Marat published pamphlets to rally the citizenry in a bloody revolution against the French aristocracy and the injustices of class war, and I thought, what a perfect topic for today!

CS: What interests me also is that you are referring to Erich Fromm's essay, and I'd looked at your earlier work of the revolutionaries and the artifacts around them. I began to think of the historical persona in relation to the essay by Erich Fromm, looking again at the blue police barriers arranged at the edges of Disobedience, and thinking that Fromm's essay is about cultural revolution, but it is also about the self at the same time. The police barriers can also be seen as the Super Ego and the rabble in the middle that is always wanting to disobey is the human self that dares to transgress the boundaries of the authoritarian self. Erich Fromm is perpetually stuck in this post-war mire where his persona is Eichmann, the Organization Man, so I was having fun with these historical personas and the artifacts that surround them, as artifacts, not reliquaries, of the self.

ACR: Artifacts is a good word, and I often use the word heirlooms to describe these things I'm making. These characters are not historically real, but a reference for the work. So the story about Jean Marat is a vehicle to examine ideas about disobedience and transgression through visual artifacts. These artifacts can be simply mundane or beautiful taken alone, but they can also be pieced together to signify a story to answer questions like what would a rebel do? What would Marat be doing today? In this particular project I imagined Marat alive today and I put him in the worst possible situation, recently fired, unemployed he is hired out as a temp worker in the complaints department of a very large corporation. Imagine the frustration and desperation of someone humiliated, downsized and degraded into temporary and menial work. As an artist I've had plenty of experience working the "B" job. I've even worked in some big financial institutions where I've have to review customer complaints and some of its personal and some of its kind of comic. So what would Marat do if he were working in a complaints department of a bank that is foreclosing on homes today! What would he experience, how would he let off steam, how would he do what Marat did, and I thought in a somewhat cynical way he might be spouting his diatribe out into the internet, out into the ether, and not really getting much of a response. And I imagined him in a studio apartment at night, after work, tinkering and building his revolution as a model at his kitchen table. I suppose the sense of impotent rage and apathetic, muted rebellion seemed familiar to me. When I was younger in the 1980's I remember the Tompkins Square riots in the East Village of New York. I was there with friends just walking in the neighborhood, and we turned the corner to be confronted by the NYPD beating the hell out of everyone on the street, knocking cameras out of peoples hands, they taped over their badges and ran amok over every one. I was struck by the violence and the terror of being on the other side of the barricade and my sense of helplessness and frustration. So wouldn't it be fun to make those police barricades impotent, turn power upside down, like a toy? To me it's amusing to watch visitors to the gallery play this out when interacting with my work. They bend down to look at it with a smile, its menacing but small, threatening revolution but on a child like scale that feels manageable.

Andrew Cornell Robinson, Trophy I, 2011, Porcelain, majolica glaze, 7 3/8 x 4 5/8 x 3 inches, courtesy of Anna Kustera Gallery

Andrew Cornell Robinson's contemporary Marat has made a few trophies in honor of the Revolution. Upon the death of Jean Marat, the painter Jacques Louis David orchestrated a variety of pageants involving the body of the deceased revolutionary. Perhaps one of the more absurd of these ritualized displays was that of Marat's heart sealed within an urn from the Crown Jewels - a parody of blind Catholic devotion to monarchical state power. Robinson's Marat heralds trophies of war, bombs and swords broken in the field, body parts and flies, parodying the great figures of Western History. And for the centerpiece of his table Robinson's Marat wows his guests with a pastry too big to fail even as it barely holds its own weight. Abject and raucous at once, this five-tiered layer cake was inspired by a 1911 labor poster and James Ensor.

Andrew Cornell Robinson, High Society I, 2011, Porcelain, majolica glaze, terra cotta, 21 1/2 x 11 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches, Courtesy of Anna Kustera Gallery.

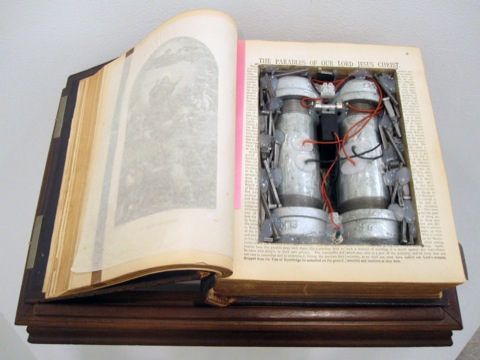

Gregory Green is perhaps best known for displaying bombs in galleries since 1992. The FBI has a file on hand for each of his bombs, so that agents do not confuse his artist's models, lacking in dynamite or plutonium, with the real thing. Several times galleries have had to contend with the law, his devices frazzling the contours of power. This put Green in the odd position of becoming a spokesperson for terrorism, to the extent that when asked if the World Trade Center might become a serious target, Green could not deny it's symbolic value and likely fall. After 9/11 this made the artist untouchable, and for nearly a decade since the art world has been consumed by decoration and (b)light - a condition that is exploited well by the forthcoming exhibition of Damien Hirst's polka dots across the Gagosian globe. Recently, however, Gregory Green has noticed a thaw - exhibition spaces are becoming a little bolder and don't fear losing their funding base because of it.

Gregory Green, Biblebomb #1884 (Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition), 2011, Mixed media, 8 x 20 x 13 inches, courtesy of Anna Kustera Gallery

Through the Night Softly was made before Occupy Wall Street began and as a commemoration of 9/11 by the artist who had predicted it. It consists of 2,552 metal tire spikes, each one crafted by the artist in honor of the lives lost on that day. Tire spikes, known variously as horse cripplers, road stars, or caltrops, are the device of a military strategy known to be in use at least since the 4th century BC, in order to protect the perimeter of a defined space. For the artist tire spikes represent not only the lives lost on 9/11 but the transitional authorities that have become increasingly present in sites of conflict, be they the United Nations, the United States, or local military police.

Gregory Green, Through the Night Softly, 2011, 2552 hand-made metal tire spikes, dimensions variable, courtesy of Anna Kustera Gallery.

Scattered across the floor of the gallery the sharply beveled edges of Green's tire spikes in Through the Night Softly glint in the halogen light from the gallery ceiling tracks, as though caught in a spotlight at night. They evoke the more abstract scatter pieces of Robert Morris or Carl Andre, but in this glinting of light are closer to Robert Smithson's Map of Atlantis and the work from which Gregory Green has borrowed the title, Chris Burden's video performance, Through the Night Softly. Where Chris Burden's own body cuts through the screen of the television monitor, Gregory Green's tire spikes pierce into the actual space of the gallery. It is the kind of move that has parody swinging over into allegory's broader and more scattered, range of effects.

Shown on television after the 10:00 news, Burden's piece was made at the height of the Vietnam War. I asked Gregory Green about Chris Burden's influence upon him, and below is an excerpt of the conversation that ensued.

Gregory Green: Chris Burden was a major influence on my work as a student in the late 70s and 80s, and in certain respects it's a homage to Chriis, but its also a natural extension of a lot of work that I've been doing for the last 20+ years. On some levels it's aestheticized and formal as opposed to my earlier works, the title itself is a major change from my normal didactic and descriptive approach to titling for instance. ...one of the things I like about through the night softly and some of the other works in my studio right now, is that in some ways they are even less defined than previous works, while also being more open, poetic, allowing the viewer to foster varied interpretations of the piece on many different levels, from a simple didactic to much more that may be tied not only to OWS, but to Burden's beautiful night sky and the potential of all of us to have a voice in our world. There was, in this installation, an attempt to re-create a little bit of that beautiful video by Chris Burden.

Catherine Spaeth: In Chris Burden's piece it's like a cracking up of the monitor screen onto the street. Acknowledging that you are turning to more poetic, formal pieces I really enjoy the way that this is interacting with the gallery space as a formal piece. In an earlier interview you described yourself as a romantic anarchist, and I notice that in your work from the first pipe bombs until now there's an interesting tension. Anarchy is a troubled word, it's so hard to use as an activist, burdened as it is by terrorist bombings, and has become a political concept torn asunder by its own meanings which can range from the terrorist bomb to the utopian harmony of bees. I see that in your work whether it's the bomb pieces or the future realization of an actual state attached to a piece of land. What I am thinking about in this particular piece is the question as to whether or not this is resistance or control in the gallery space. What kind of meanings accrue to power as its handed to us by such a thing as the gallery space?

GG: That's something I've been exploring my entire career in all of my various bodies of works. Subverting and disrupting the ivory tower, the white box, and to change not only what the viewer might expect when entering a gallery space, but also the physical space itself and its traditional relationship to the outside world. Its sense of authority, safety and other related issues. My relationship to the art world has varied throughout my career, there has been a love of it and an educated occasional suspicion. So these pieces are intended to break up the standard relationship and expectations of the viewer and public to that space.

CS: But you are in practical daily life drawn to pacifisim, how does the Free State of Caroline belong here, it's a documented concept that's going to take a different shape as things turn in history. The difference between our first invasions into Afghanistan, to a model of intentional community such as Zuccotti Park changes the parameters of the imagination for such a place as the Free State of Caroline. How do you see your work shifting in response to historical situations?

GG: The project started out on a pretty straightforward level of trying to get recognized authority, trying to claim and establish my own territory, country, community. From the very beginning I was uncomfortable with the megalomaniac aspects of the basic idea, and over time parodying the idea of creating your own country became more and more prominent within the project, to the point where now it's the primary strategy within most of the recent New Free State of Caroline works. One of the things that Caroline does, as well as some of my other bodies of works, is to exist primarily within the real world, outside of the gallery space. It's a form of relational intervention, social sculpture, or as Jeffrey Deitch once described it in an essay for the Saatchi Gallery, "conceptual terrorism". One could think of myself and the works as a form of a merry prankster, disrupting the normal flow of the system, even if symbolically. In many ways that's what the Occupy Wall Street folks are doing.

Catherine Spaeth is an art historian and critic currently lecturing at Purchase College and the Pratt Institute.