They're demonstrating on West 45th Street in New York again. Seventy-seven years ago, crowds swarmed from Pennsylvania Station to West 86th Street, shouting "Free the Scottsboro Boys." Now the message is protest the Scottsboro musical, which is currently running on Broadway. The case still inflames passions.

I admit I approached the play, which I saw off-Broadway, reluctantly. Having spent several years researching and writing a book about the incident and its almost half-century aftermath which convulsed the country and reverberated around the world, I could not imagine how this agonizing and shameful chapter in our recent past could be turned into a musical.

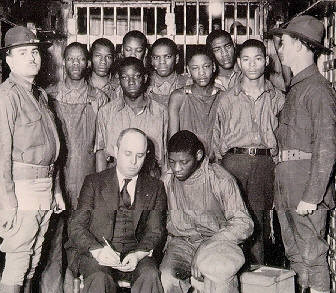

The story is chilling. Briefly told, in 1931, a year when the economy was in even worse shape than it currently is, and more than 200,000 kids under the age of twenty-one were hopping freight trains, and hitchhiking, and hoboing around the country in search of an odd job, or a few scraps of food, or the little bit of fun that is supposed to be the birthright of youth, an Alabama posse stopped a freight train and rounded up nine African-American young men and boys. They tied them together with a plow line and loaded them into the back of a flatbed truck to take to the local jail. Then the posse found two girls in one of the freight cars, and though they showed no signs of abuse, fast as anyone could say Jim Crow, the cry of rape went up.

In four days, and with grossly inadequate and probably drunk defense counsel, the state of Alabama tried, convicted, and sentenced eight of the nine defendants to the electric chair. A mistrial was declared for the ninth, a thirteen-year-old, whom some, but not all, of the jurors deemed too young for capital punishment.

The musical Scottsboro is electrifying theater. My reluctance to see it evaporated only minutes into the opening number. The cast is young, vibrant, and hugely talented. The score by John Kander and the late Fred Ebb, while not as memorable as Cabaret or Chicago, is rousing and witty and sophisticated. And the minstrel show format, while often jarring and offensive, as it is meant to be, displays plenty of stagecraft. Perhaps that is the problem.

Stagecraft is meant to dazzle. By nature, it lacks subtlety, nuance, or ambiguity. In this particular minstrel show, the nine Scottsboro Boys, as they became known, are heroic. It is no accident they wear white. Everyone else in the cast is racist, venal, opportunistic, or a combination of all three.

The boys were admirable in many ways. Several of them taught themselves to read during the long years they spent in jail. Haywood Patterson, the brilliantly portrayed heart and pivot of the show, lived a life in and out of prison that is both horrifying and inspiring. But they were not the only ones in white hats. Many men and women endured hardship, jeopardized their careers, and risked death to try to clear the innocent young men. Not all of them were northerners.

Judge James Edwin Horton, Jr., who presided over one of the trials and set aside the verdict, was voted out of office and never served again. The poet Muriel Rukeyser was thrown into jail, where she contracted typhus. But perhaps the character most ill-served by the musical is Samuel Leibowitz, the chief defense attorney who was the catalyst for that demonstration so many years ago.

Leibowitz was an ace criminal defense attorney, who had won acquittals in seventy-seven of seventy-eight first-degree murderer cases, with one hung jury. His clients were not the most savory characters, but he was a scrupulous and courageous man. A liberal FDR Democrat, he made the International Labor Defense, a communist front organization which approached him to defend the boys, promise it would not interfere with his handling of the case. (It will surprise no one to learn that the ILD welched on the promise.) He paid his own expenses. Most important, he risked his life.

Inside the courtroom, anti-Semitic slurs flew. Outside, rabble-rousers called for lynching the Jews as well as the blacks. One pamphlet on sale during the third set of trials was entitled "Kill the Jew from New York." His wife so feared for his life that she jeopardized her own to go down to Alabama to cook for him. She was afraid not of the kitchen staff, who were African-Americans, but of others who might slip something into his food on the way from preparation to table. Nonetheless, Leibowitz repeatedly turned down offers of protection from the local National Guard, though he did accept the two detectives sent down by Mayor LaGuardia. He was, after all, a New Yorker.

Though the play has a witty and devastating song about anti-Semitism, it nonetheless portrays Leibowitz as a crass opportunist determined to climb to the pinnacle of his profession on his clients' backs. His defense of the Scottsboro boys did propel his career upward. Such is often the result of being in the forefront of a fight for a just cause against insurmountable odds. I believe he was sufficiently savvy to suspect that would be the result when he took the case. But to suggest that personal ambition was his sole or even central motive plays fast and loose with the facts.

The word Scottsboro has become iconic in American lore. Everyone knows it stands for a terrible racial injustice. But these days few know the details of the incident or its long aftermath. That is why it is so important to get the retelling right. And that is why the musical Scottsboro, for all Kander's and Ebb's good intentions, the cast's prodigious talent, and the production's high spirits and polish, does not so much illuminate a terrible injustice as perpetrate one more Scottsboro myth.