In the previous blogs in this series, we looked at the unique underlying terms of the Business & Human Rights (BHR) field that have arguably led to its booming success in the last decade, at least in terms of corporate engagement. We also looked at prominent voices that have recently expressed concern that these terms -- the magic "&" that brings these two once disparate worlds together -- may not be sufficiently mutually understood to lay the foundation for the move from an era of so-called "groundbreaking" commitments to an era of measurable progress. Along the way, I suggested that a key issue was resource disparity and negotiating power: that it is and will remain a constant struggle on the human rights side of the & to not fall into a secondary role in response to the business world's agenda-setting (and profit-maximizing) instincts.

What's missing?

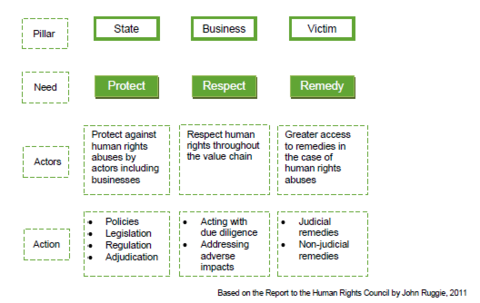

If the problem is conceptual drift, pushing back on the surface level will only go so far; the real answer is the structure that is failing to hold. For structure, we need to look all the way back to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), the foundational text whose negotiation created the BHR deal and set the stage for all to come. The UNGPs set forth the "Protect - Respect - Remedy" Framework: three "Pillars" that reference core principles and also serve to allocate or divvy up responsibility between core stakeholders. Consider the fuller statement of the three pillars in the form of the chapter headings in the final UNGP document:

Is something missing? I have always thought so. The first two pillars establish a nice subject-object rhythm: X has a duty to advance Y. I'm no MBA, but even I recognize this as sound management practice: immediately upon creating a task, giving someone primary responsibility to complete it. The elaboration of these Pillars in the principles that follow each heading are as expected, with Section I principles describing what "States must..." do and Section II principles describing what "Business enterprises should..." do.

But then there is a jolting transition to the Third Pillar, which is stated passively and not assigned to any particular stakeholder or institution. Digging into the principles, we find that the UNGPs actually allocate responsibility for the Third Pillar to the subjects of Pillars I and II -- States and business enterprises -- with four "States should" principles, one "business enterprises should" principle, and one "[i]ndustry, multi-stakeholder and other collaborative initiatives should" principle.

If fulfillment of the Third Pillar is to be accomplished by States and business enterprises, why not just include these responsibilities among the many others assigned in Pillars I and II, respectively? This is how BHR practitioners have received it in substance: for example, a prominent UNGP "toolkit" for states produced by the International Corporate Accountability Roundtable (ICAR) simply lists the State obligations as consisting of ten principles from Pillar I and five from Pillar III.

A reason to not just "leave it at that" is because, below the surface, the three-pillar system may be more cogent, just incomplete. There is a constituency, a stakeholder, an institution in the broadest sense, whose natural (though not exclusive) role is to assure fulfillment of access to remedy. When Oxfam approached this question in a 2013 technical briefing on the UNGPs, it tried to resolve it by casting victims as the source of agency behind the Third Pillar:

In my view, this comes close, but remains incomplete. The actual source of agency, or constituency, or institution behind Pillar III is victims' advocates, or perhaps victims and their advocates. The community leaders, organizers, lawyers, public interest groups, issue-based groups, and other components of civil society that have, in fact, led the fight for meaningful remedy for decades. Where are they in this Framework?

Issues with advocates

I have found the reaction that I get when I pose this idea -- that victims' advocates or civil society are the natural heirs of Third Pillar responsibilities -- to be telling. It is dismissive, to be sure, but it also often carries a whiff of contempt, even from members of the advocacy community itself. Who are they (advocates) to think they deserve such a prominent role? And yet, as noted, this dismissiveness is completely counter-factual: advocates have always sustained the demand for remedy, and it was civil society that arguably conceived, and certainly drove, the process that (with many twists and turns) led to the UNGPs and BHR in the first place. The core enterprise of BHR has been, as described by one leading professor in the field, "getting states, businesses, and civil society actors ... to actually talk to each other." These three, in the real world, are your pillars.

Some of the resistance to the idea of advocates as a Pillar may come from legitimate concerns about advocate domination and the need to preserve the agency of victims to speak for themselves. But some of it appears to be a perhaps unconscious reflection of a narrative propagated by business groups and their allies over the last few decades that has sought to cast advocates -- lawyers, in particular, but also community leaders and to some extent victims themselves -- as greedy, corrupt, and even criminal. In a well-known broadside, originally funded by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce but quickly transplanted in academic, policy, and public opinion circles, Jonathan Drimmer characterized human rights remedy efforts as "the plaintiffs bar go[ing] international" in "an effort to inflict maximum punishment on companies" and "force them into lucrative settlements." Another writer referred to remedy efforts as the "new plaintiffs-lawyer product line." A more recent Chamber of Commerce report took direct aim at novel efforts to finance the upfront costs of pursung a remedy (costs being a salient and unresolved problem in the remedy discussion), demonizing them as the "sale" of lawsuits, unethical across the board. A recent U.K. law aimed to shut down the economic model that had supported a small handful of successful human rights suits. Beyond lawsuits, corporations (and states) have attacked a range of advocacy and activism tactics as everything from irresponsible to criminal.

Self-fulfilling prophecies

These attacks can only be fully understood in relation to a critical underlying truth which they are designed to conceal, and, indeed, that our own sense of justice often helps conceal as well. Remedies don't happen by themselves. We want to believe that a truly meritorious case will somehow float its way to a just resolution, perhaps on the winds of benevolence -- the corporation will recognize the gravity of its wrong and offer to make amends; the judge will recognize a deserving victim's lack of sophistication and act to prevent her from being crushed by litigation tactics; the truth will, somehow, come out. But the reality, at least outside of jurisdictions that host a relatively powerful institution of advocacy (such as a "plaintiffs bar"), is that corporations almost never settle and rather have proven adept at outmaneuvering and overwhelming their adversaries in courts and similar forums with little or no resistance. What we know about remedies is not only that they don't happen by themselves, but that they tend to require years or even decades of struggle and single-minded focus to come about.

Of course, as noted above, remedies are not left to themselves in the Framework, but rather are committed to the responsibility of States and businesses, the subjects of Pillars I and II. But leaving the remedy pillar in these hands is not an inspiring strategy. States and businesses are essentially the targets of remedy; the liability-holders. Pillar III tries to address this conflict of interest by endorsing only "access to remedy"; a crafted compromise that seems related to the (true) fact that not every remedy demand is meritorious. But distancing the right by providing only "access" to it raises the spectre that the principle would tolerate the provision of remedial process that falls short of a remedy even in a meritorious case. While we know that this describes the real world -- meritorious demands for remedy will sometimes fail -- it should not be built into the system. The entire BHR enterprise presumes the existence of some business violations of human rights; as to those violations, there is no good reason why the right to a remedy cannot and should not be absolute in principle.

Even putting the "access" obligation too squarely into the hands of states and businesses is problematic. States tend to think that their protection efforts under Pillar I obviate or undermine the urgency of the need for remedial processes, at least with respect to that aspect of remedy that goes beyond individual compensation and seeks to set precedent and institute reform. As a practical matter, a comprehensive ICAR review of state National Actions Plans (NAPs), required under the UNGPs, reports that while states are making slow progress in understanding their Pillar I obligations, "in most of the NAPs [Pillar III] is addressed only very briefly or not at all." Another ICAR report details the layers upon layers of obstacles that victims, usually poor and beleaguered by multiple forms of harassment, face when they consider bringing their claims to existing justice systems, and observes that not only is the situation not improving since the adoption of the UNGPs, but rather many States "have taken regressive steps" to keep a remedy even further out of reach.

So while states will inevitably have the obligation to provide the platform and ultimately deliver the remedy, a broader or more essential responsibility to fulfill, effectuate, or drive the right to remedy lies elsewhere. While it might seem strange to give responsibility for remedy to an institution that doesn't technically have the power to deliver it, victims and their advocates do ultimately have the most relevant power -- the power of the right, the power of the demand. And, to the extent they lack power, giving them responsibility only helps empower them.

Recognition and enforcement

Recognizing the Pillar-esque role played by victims and their advocates would provide a strong and much-needed dose of validation. The Pillars impose responsibilities in the sense of duties, but they equally provide responsibility in the sense of authority. If you have responsibility to carry something out -- to assure access to a remedy -- you necessarily have authority to act, and others may have an implied responsibility to help you, or at least to not stand in your way. Articulating advocates' role in the system could also help clarify ethical guidelines and push the broader BHR community to reach consensus as to the legitimacy and necessity of many aspects of advocates' work. The corporate demonization narrative noted above feeds on outrage over the fact that victims and advocates engage in tactics such as "public-relations campaigns complete with documentaries, community organizing, political lobbying and efforts to drive down stock prices of companies and multinationals with a U.S. presence." Yet most advocates consider these kinds of tools to be perfectly legitimate -- and absolutely necessary given the practical impossibility of surmounting the obstacles imposed by States and businesses to the remedies they purport to provide.

Understanding advocates as a constituency or "institution" under Pillar III would also serve to support the solidarity, intersectionality, and collective influence that advocates for victims always seek, but that can be hard to prioritize given the brutal pressing realities of their individual struggles.

And then there is the question of negotiating power. As we saw particularly in Part II of this series, there is an ongoing tug-of-war in BHR over not just leadership but who is defining the content of key terms of the BHR deal as we move from principle to practice. How can victims, advocates, and civil society expect to maintain their due role -- and the primacy of human rights in the framework generally -- without a proper and cogent seat at the table? The problem here has been obscured in part because some elements of civil society do have influence -- lots of it. But a look at who exercises this influence and how only deepens concerns about what exactly business has agreed to as part of its engagement with the BHR framework.

Agree to disagree

As noted, certain leading civil society organizations were key players in creating the BHR framework in the first place, and today continue to play an absolutely central role, almost like Masters of Ceremony in the way they drive the conversation. Among these I would include ICAR, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), the Institute from Human Rights and Business, Oxfam, and a few others. The part of the BHR/Pillar III deal that seems clear is that the business community agreed to engage with and accept this segment of the advocacy community, along with the conceptual importance of remedies as a general matter. But what about the countless, more local and situation-specific advocates -- the community leaders and organizers, the local unions and human rights groups, the local lawyers, and of course the victims themselves? These groups and individuals may at times find themselves in solidarity with others on larger systemic issues, but their fights are fundamentally local and always geared toward remedy. Their demands are the beating heart of the larger, conceptual BHR insistence on remedy. Did the business community agree to engage with and accept the legitimacy of these advocates as part of the BHR deal?

It is one thing for a mining executive to sit down with a professional issue advocate from an elite NGO and discuss the concept of remedy generally. It is another to sit down with a local organizer, who not only has dirt under her fingernails but that dirt has contamination from the executive's mine, and she wants to know specifically what the executive intends to do about it. The BHR framework seems designed to avoid the latter: companies instead conference with governments (and, de facto, elite NGOs) to decide what rights mean and what remedy structures should look like, and then engage communities (often through consultants) to realize the substance of those decisions in specific situations. The suitability of this model for the sorts of real disputes that now lurk just outside the BHR campfire is questionable. It's not so much that victims and their advocates will insist on being included in these higher-level, scoping decisions (although this is true), but that they hold unique information about their situations, their demands, that is going to be necessary to reach legitimate and sustainable resolutions. In the U.S. context, victims' advocates (read plaintiffs' lawyers) have been particularly demonized, but looking past the rhetoric and the handful of bad apples, one finds individuals who think deeply about the issues at stake in the remedy concept and whose responsible efforts have been key to achieving just resolutions and critical reforms across countless situations and industries.

Remembering the Forgotten Pillar

Similar to the critique that companies should not be allowed to divert attention from their negative impacts by sponsoring heart-warming human rights promotion projects elsewhere, companies should not be able to embrace the importance of remedy in the abstract while rejecting it in the specific form it is served on them. They should not be able to embrace remedies without explaining how remedy is served by its lawyers moving to dismiss a case from a jurisdiction capable of rendering and enforcing a verdict to a jurisdiction where those capabilities are in doubt. And returning to the rather sound logic that corporations inherently lack the incentive to hold themselves accountable and understand the scope of their impact, any company-led remedy efforts such as Operational Grievance Mechanisms (OGMs) should be understood to require a much higher standard of independence than has been seen in the initial round of efforts.

States and businesses lack both the perspective and the incentive to hold the line on these devilish details. Indeed, they never have. The sprawling, multi-faceted "institution" of civil society and advocacy (yet no more sprawling and multi-faceted than business, or even states) always has.

Many have taken to calling Pillar III the "Forgotten Pillar." Reports have been issued, projects have been launched, high-level meetings have been convened. These are all important steps. Yet consistent with the theme of this blog series, real reform may lag until human rights advocates force some reconsideration of the terms of the BHR deal, which in this case might be a renewed understanding of their role or some other way of addressing the Third Pillar's almost built-in lack of leadership. A firmer place for advocates in the BHR framework would allow it to better reflect the real world of disputes and thus better facilitate real remedies and resolutions.