A North Korean Taepodong-2 missile is about the size of six U-Haul vans sitting bumper to bumper. North Korea is smaller than Mississippi. So how is it -- given a skyful of satellites, every other manner of electronic surveillance and legions of human spies -- that we were surprised by North Korea's April 5 Taepodong-2 launch?

At the same time, the lives of Kim Jong Il and his family could be made into a soap opera. How is it that we remain in the dark not only about which of them will succeed Kim, but, at times, whether they are alive or dead?

How is it that we know so little about North Korea?

Research for my novel Once A Spy (Doubleday, 2010) has brought me into contact with an array of intelligence community personnel and experts ranging from a temp to a Director of the CIA. I asked several with relevant experience: What's the problem with intelligence collection in North Korea? And what, if anything, is being done about it? Taepodong-2s currently are capable of reaching the United States. Granted, they are the Edsels of ballistic missiles. But the North Koreans (a) are working out the kinks, if this week's nuclear tests are any evidence, and (b) might sell the technology to all comers.

The primary obstacle to collecting intelligence on North Korea, I learned, has been the country's singularly insular nature. As has been well-documented, practically no civilians have telephones, let alone access to e-mail. A glance at a nighttime satellite imagery may best sum up the situation: "You see South Korea all lit up; the North is completely dark," says an expert on the region (not the temp*).

And even if we were to airdrop BlackBerrys to all North Koreans, it's doubtful that we would learn much, the latest escapades of Kim's personal troupe of strippers notwithstanding. "Gossiping can get people shot," said the expert.

The bottom line, according to an intelligence analyst:

Lack of sources in a highly dangerous, ethnically defined, ruthlessly guarded area. We tend to rely on third parties for access to such areas. Look at how hard the National Clandestine Service is trying to reinvent itself to deal with the realities of Iraq and Afghanistan, away from the consular cocktail party environment of the cold war.

A case officer adds:

We don't have any decent agents [North Korean nationals recruited by American intelligence officers]. It's simply too risky to communicate with them. And it's not that North Korean counterintelligence is especially good, it's that the society is so closed that information is strictly compartmented and there are very few opportunities to recruit penetration agents or for defectors to defect. To know what's going on in North Korea you have to penetrate at high levels of government, and to know plans and intentions you need to be in Kim's office. We don't have an embassy or other secure facility to work out of. We're more or less limited to legal traveler operations where we brief people before they go in and debrief them when they return.

I also spoke to former CIA operations officer Ishmael Jones (a pseudonym). In his memoir The Human Factor: Inside the CIA's Dysfunctional Intelligence Culture (Encounter, 2008), Jones writes:

After President Bush gave his 'Axis of Evil' speech, the Agency began sending my colleagues on missions to these and other rogue states. They didn't conduct any intelligence operations there -- just visited, stayed in hotels and returned to write detailed after-action reports about their itineraries...This became known around HQs as Axis of Evil Tourism.

While recognizing that "the new administration and the CIA get a pass for the incidents in recent days because North Korea is such a difficult place to operate," Jones faults the agency historically: "North Korea is our oldest and most obvious intelligence target," he told me. "We've known it for sixty years. To get at the target, we had millions of South Koreans who spoke the language and had relatives in North Korea. Even using our antiquated embassy structure, we should have been able to establish intelligence networks. More than ninety percent of [CIA] employees live in the United States. We need to get more of them abroad, closer to the targets."

In the interim, what about all of our satellites and drones? (The Musudan-ri test facility reportedly is watched more closely than the ball in Times Square on New Year's Eve, and, for what it's worth, the Taepodong-2 was photographed during the preparation for its April 5 launch).

"Eyes in the sky can't tell us everything we need to know," says the case officer. "[The North Koreans] could be moving empty tubes around for all the eye can tell."

Accordingly, the bulk of U.S. intelligence on North Korea, what there is of it, comes from our liaison counterparts in South Korea, Japan and China.

"The South Koreans [Agency for National Security Planning] have an ear to the ground and an ability to penetrate that the others don't," the regional expert says. Adds the case officer, "But they have the same problems we have. Japan doesn't have a foreign intel service -- unbelievable but true. They use a branch of the National Police, which is now very good." On the North Korean case, however, "basically all they do is liaise with other intel services."

And China? The Ministry of State Security plays it close to the vest. "The Chinese may pay lip service to UN attempts to get North Korea to drop its nuclear program, but they won't do anything concrete about it," the case officer says. "China isn't a target and it gets some pleasure from the fears the rest of the region displays over North Korea's aggressive behavior."

So what do we do?

Logic dictates that the threat of being turned to powder will deter North Korea from launching a Taepodong-2 at the United States. The problem is that logic may have no role in Kim's planning -- it's debatable whether "Dear Leader" is crazy like a fox or garden-variety certifiable. In either case, the threat remains that he'll sell nuclear material -- or even a plug-and-play atomic bomb -- to Al Qaeda.

So our dealings with North Korea have become analogous to a hostage situation -- think Kim wearing a vest packed with high explosive in a crowded shopping mall, his finger on the button. Our diplomats negotiate with him. Meanwhile our intelligence agencies scramble behind his back for ways to neutralize the threat.

Myriad plans for removing him from power have been and continue to be explored. The fresh regime-changing wounds from Iraq dim even staunch advocates' enthusiasm, however. And then there's the youngest of Kim's three sons, Kim Jong Un, the odds-on favorite to assume the top spot in Pyongyang: He may cause us to look back fondly on the devil we knew.

As a result, continued isolation of North Korea is regarded as the best tactic for now, the goal being containment. In the worst-case scenario, should Kim Jong Il push the button, the hope is that America need not respond unilaterally -- after all, others have more chips on the table.

The greater hope is that the CIA or DIA or NSA or SEALs have some other, innovative operation underway -- an operation about which a novelist has no need to know -- that will yield a better outcome.

*I prefer not to use anonymous sources, but this post would consist of little more than questions and conjecture otherwise. One source at least publicly uses a pseudonym.

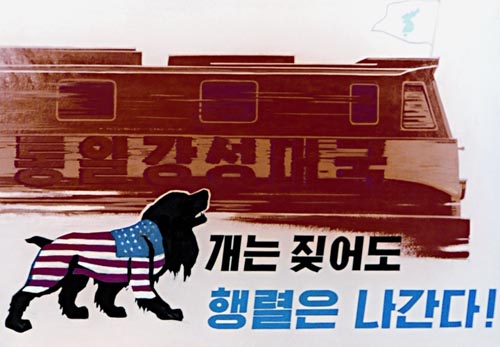

"When provoking a war of aggression, we will hit back, beginning with the US!"

"Though the dog barks, the procession moves on!"