Wentworth Miller first became widely known for his looks in a Mariah Carey video, and then through the starring role in the 2005-2009 Fox series "Prison Break." But despite possessing just about everything that's valued in American society today--fame, beauty, money--Miller's life wasn't easy. Perez Hilton and similar blog bullies posted photos of Miller strolling and riding in cars with gay actor Luke MacFarlane (who had a starring role as a gay character on ABC's "Brothers and Sisters"). Along with these photos were, for lack of a better word, accusations that Miller was secretly gay. Miller responded by denying his rumored sexuality, which is always a lose-lose proposition for anyone in the public eye: doing so more often than not only fuels bloggers' fixation on outing a celebrity, while also giving everyone permission to accuse the celebrity of being anti-gay.

Miller eventually came out via an open letter published on the GLAAD website in 2013.

For many LGBT people--and I am no exception--such apparent hypocrisy conjures mixed feelings. On one hand, it can feel like an offense to our nature to witness someone deny his or her sexuality, because doing so implies there is something shameful about it. On the other hand, all of us (or at least those of us of a certain age) understand how difficult it is to be honest about who we are when society overall condemns our natures, and the courage it takes to go against a culture has to be amplified exponentially for someone whose private life is fodder for tabloids.

If a person has to do a mea culpa for denying his or her sexuality, Miller's 2013 speech to the Human Rights Campaign is a strong template. Heartfelt, genuine, and so confessional that it's hard to watch, Miller's speech describes cultural pressures that made it difficult for him to accept his sexuality--but he came to terms with it eventually, and in the process struggled with severe depression and suicidal thoughts.

A central part of that speech deals with community:

I've had a complicated relationship with that word, 'community.' I've been slow to embrace it. I've been hesitant. I've been doubtful. For many years I could not or would not accept that there was anything in that word for someone like me. Like connection and support, strength, warmth.

Ultimately, Miller accepted that he is part of the LGBT community--which can be a warm and accepting place--it has to be said--especially for someone who is conventionally attractive. Gay or straight, many men are eager to accept a pretty package.

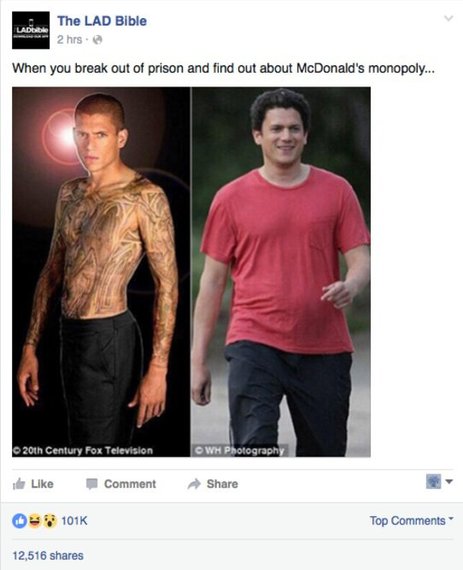

But what happens when pretty turns...well, average? This morning on Twitter, I saw a story detailing Miller's response to a fat-shaming blog post comparing side-by-side photos of Miller shirtless in his "Prison Break" heyday and then in 2010 at his heaviest, burdened by the evident weight of depression. In his response, Miller discloses that he was suicidal at the time, having struggled with mental health challenges throughout his life.

The same story appears in UK LGBT magazine Attitude, followed by a phone number for a suicide hotline, followed by a link to an article (actually just a collection of photos) called "Wentworth Miller's Hottest Moments." It's probably unnecessary, but I'll just take a moment to point out the (typical) irony of an LGBT publication following a story about a gay man being driven to suicidal ideation in part by being shamed for his body with an article celebrating the man's body when he was in better shape.

This is where, for me, community is everything. I've written about it before and I'll write about it again as long as I have a platform, but gay men have to find a way to appreciate other gay men for more than appearances.

Many of us were upset when we read last week that gay country singer and underwear model (whom I'd never previously heard of) Steve Grand claimed victimhood for being a "young, good-looking, white gay" man. The reason for offense isn't jealousy; it's because we know that conventionally pretty people are prized and treated as royalty by the gay culture, and just as it may be human nature to give preferential treatment to those who are conventionally attractive, it may be human nature to resent Marie Antoinettish hypocrites who want to have their cake, eat it, too, and all while complaining about not having enough of it.

We have to do better as a community. For every Wentworth Miller who is beautiful and strong enough to overcome deeply seated depression anchored in shame about sexuality and appearance, there are countless ordinary, plain, overweight, non-male-model types who are equally human and equally deserving of respect. It's not politically correct to say so, but I'm far from the only gay man who feels that, as Lamar Dawson wrote yesterday, "some gay men [watched] Mean Girls and took it a little too seriously."

When we think about the disturbingly high rates of suicide among LGBT people, we tend to associate the depression that leads to it with bullying by straight people. This is its own form of gay denial. I know it and you probably know it, too, even if Steve Grand, Davey Wavey and the ghost of Marie Antoinette will remain eternally oblivious.

We -- gay men -- need to be able to look at chubby Wentworth Miller and see through the packaging. We need to be able to look at hot Wentworth Miller and see through the packaging. We need to relearn what it means to be fully human, to look at Joe Average and understand that the skin and muscle are only the decorative containers for hearts and minds that contain deeper, more rewarding forms of beauty. People in other strata of society -- albeit not those featured on the Bravo network -- value these invisible aspects of what it means to be human. Maybe we should, too.

___________________

If you -- or someone you know -- need help, please call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. If you are outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention for a database of international resources.