Is knitting news?! How could it be; knitting is so boring. Maybe, but then again, maybe not.

In this ongoing foray into Forgotten Women, sometimes a single, and singular, woman, such as Madame C.J. Walker, gets the focus; sometimes it's a group, like the women of the MCNY Notorious & Notable exhibition; and sometimes it's an amorphous group that (excuse the pun) knits us all together in our shared humanity. In this case, that would be women who knit.

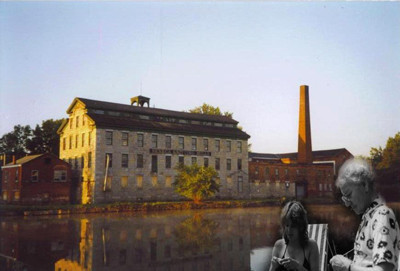

Knitting has in fact made news lately: The National Women's Hall of Fame announced its list of 11 new inductees on March 8, making up 247 women whose stories will soon be told in their new home, the Seneca Knitting Mill. The imposing limestone structure, whose elegance lies in its simplicity and solid utility so characteristic of the country's burgeoning Industrial Revolution, was built in 1844. It ran continuously for 155 years, employing mostly women (operating the knitting machines, sewing socks together, etc.) until it closed in 1999.

Knitting has in fact made news lately: The National Women's Hall of Fame announced its list of 11 new inductees on March 8, making up 247 women whose stories will soon be told in their new home, the Seneca Knitting Mill. The imposing limestone structure, whose elegance lies in its simplicity and solid utility so characteristic of the country's burgeoning Industrial Revolution, was built in 1844. It ran continuously for 155 years, employing mostly women (operating the knitting machines, sewing socks together, etc.) until it closed in 1999.

The NWHF hopes to begin work on the site this year. The Seneca Falls institution, which began in 1969 as a way to honor the birthplace of women's rights (1848, four years after the Mill was built, marked the first Women Right's Convention) will move from its current locale in a converted bank building to its new home.

I couldn't help but think how extraordinarily fitting this is, based on my conversation with Debbie Stoller, author of the "Stitch 'n Bitch" knitting books. I first met Stoller when I interviewed her for the release of her most recent book in the successful series, "Superstar Knitting."

But Stoller has another "day job" in addition to her knitting tomes, as editor of Bust, a feminist magazine that she began on a shoestring (or should I say a strand of yarn?) back in 1993.

Her interest in feminism took hold as a child: "The women's liberation movement was booming all around me," she says. But knitting was woven into her Dutch ancestry on her mother's side, and she "grew up with needlecrafts." Summer vacations were spent in Holland with aunts and her beloved grandmother (pictured inset, teaching the author to knit), where Stoller felt that "home and domestic life [were] more valued... elevated, admired and respected."

She remembered her American aunts as busy working women who "didn't even know how to sew on a button." When she and her siblings would attend family gatherings wearing the clothes her mother made, the aunts would say, "Oh that's so cute; can you make one for my daughter?"

Her back went up, Stoller remembers: "I felt insulted for my mother, as if it took no work, time or skill at all to make these clothes." She also notes, with wry amusement, the disconnect women bring to the Stitch 'n Bitch knitting circles when they first join: "They think they'll leave in two hours with a completed scarf." Both are indicative of how the work is underappreciated and devalued, she says.

Stoller's attraction to feminism eventually landed her in grad school for psychobiology and social psychology, but she was acutely aware of "straddling two different cultures. ... My feminism is tempered by having a close connection to a non-American culture."

In pondering women who "are important in history" (she gives Amelia Earhart and Joan of Arc as examples), she realized recognition came only for the ones who "did the same kinds of things men have always done. ... [Their accomplishments] had value, because it's what men do." Her intent is to reclaim the value of endeavors like knitting; she asserts that there really is no disconnect between this kind of work and the feminist mindset.

This prompted me to look into to heroes of knitting: Mary Walker Phillips, whom the New York Times said "liberate[d] knitting from the yoke of the sweater" and "gave it bold new life as a modern art form to be displayed on the walls of museums around the world."

Or Elizabeth Zimmerman, who brought a mathematical precision to the craft that the New York Times termed "a sculptor's sensitivity to revolutionizing the ancient art of knitting." Zimmerman is know for stating, "Knit on with confidence and hope, through all crises." Her obituary also included a quote noting that Zimmerman "brought intelligence and validity to a craft that had been trivialized as women's work."

This underscores the hierarchy of importance that has taken root, which bears reexamination. In reading through other articles marking Women's History Month, I came across Marianne Williamson's "Feminism 2.0," which perfectly articulates this situation:

Women worked hard, and many at great personal sacrifice, to provide for the modern Western woman the extraordinary opportunities and powers that we now enjoy. ... [Y]ou come to realize that as far as a difference between being "out in the world" and "being at home" is concerned, there actually is no difference.

So the gorgeous symmetry of having the NWHF in the knitting mill is threefold: the Industrial Revolution marked the beginning of women moving into the workforce in large numbers; working in a knitting mill was a curious hybrid of women's "home" work transferred to a professional setting; and finally, knitting represents the women who kept the home fires burning, the food on the table and in our mouths that nourished us, the clothes on our backs so that we could go out into the world and tackle the realms of politics and business, arts and sciences. For most of those who have accomplished such acknowledged feats had wind beneath their wings, or in this case, knitting needles propping them up.

The NWHF does plan to "pay tribute to the Mill and the industrial workers of Seneca Falls." Perhaps there will be a special corner in their new home for those famous and faceless women who kept the needles clacking 'round the world, to remind us and to remember our interconnectedness and interreliance.

Because, in a sense, we're all a circle of knitters -- whether it be knitters of words into ideas, knitters of communities, knitters of families -- all forming the fabric of a society in flux, and weaving together our shared history.

***

For more on women then and now, see Gerit Quealy's column on StyleGoesStrong.com.

Image of the Seneca Knitting Mills courtesy of the National Women's Hall of Fame; black-and-white image of Debbie Stoller and her Dutch grandmother courtesy of the author and Workman; special thanks to Maureen Conlon.