One of the cool things about travel is that it is like being a baby: everything is new, and the smallest achievement is a triumph. I promised myself a week to get acclimated, without having to produce anything noteworthy. Here is the first three and a half days:

Arrival: My apartment is in Pest near the Margit Bridge and St. Istvan Blvd. I take the mini-bus from the airport and enter through a heavy double door into a covered hallway with chipped mosaic tiles and a courtyard. After lugging my suitcases up a flight of stone steps, I find my apartment, with curtained glass double doors, and many locks, on the outdoor corridor.

Say what you will about stereotypes, there are definite national and cultural traits. Resourcefulness is not one of Hungary's. "Nem tu dom" in Hungarian means "I don't know." It is a conversation stopper. If you ask someone where to find something or how to do something, the answer is simple: Either they know or they don't. If they don't, they turn away. The idea that they might find out doesn't even occur to them. The young woman who has come to let me into my apartment, a recent college grad in Marketing and Communications, does not know how to turn on the heat or load the washing machine. Nem tu dom. There are all sorts of things she does not know, although she has been paid by my landlady to orient me. She just shakes her head.

My friend, Berne, an expat of 15 years teaching Business Communications in the university here, says that while no one liked Big Brother, everyone still expects someone out there to take care of things. They shrug. It may not be taken care of well, but it is not their responsibility. I shrug in return.

My apartment is spacious and airy with high ceilings and French doors, decorated in a sort of European shabby chic, with lots of fringed lampshades and oriental rugs. In a word, perfect. I spend the evening unpacking and, like an animal, marking my territory. All my clothes are put away, and I have managed to turn on the hot water heater.

Day One, Easter Sunday: When I awaken, happily rested after 12 hours of sleep and much melatonin, I have a wicked cold, picked up from the airline air, exacerbated, no doubt, by breathing in side smoke in the Kiev airport. I make coffee and loll about till afternoon. Fortunately, I brought along plenty of vitamin C and golden seal.

Eventually I go out to explore the neighborhood. The shabbiness of people's clothing surprises me. I saw this when I was here in 1979, but I thought 20 years of capitalism would have changed the poor quality of fabric and work. I walk over the Margit Bridge, where I can see the Danube, the Basilica, and the Houses of Parliament. I am here at last. Young people with bicycles are meeting and greeting. I wind up at the Europa Café, where I indulge in a Makos pastry, light pastry dough filled with poppy seeds, while I watch people. I imagine what they are saying from their body language. It seems the women are complaining or whining about something, and the men are either annoyed or trying to placate them. Nem tu dom. No place to go and nothing to do. I can't even read. I came with only one slim volume of T.S. Eliot's poetry, Four Quartets, about engaging with emptiness.

With some trepidation I manage to put my debit card into the ATM and get out Hungarian forints (I have read that cards sometimes get eaten by machines here). Delighted with my achievement, I buy tomatoes, water, wine and some sort of smoked fish. I get take-out for dinner with as many vegetables as I can find. Whatever it is, I eat it at my kitchen table. It is delicious! I am happy.

Day Two, Easter Monday: I still have some sniffles. It is gray and raining outside my window, but I am undaunted. Foregoing the pencil skirt and high-heeled spectator pumps I had planned for a more sensible ensemble of Katherine Hepburn pants and rubber-soled walking shoes with my new raincoat, I head out to Szent Istvan Basilica for Easter Monday Mass. I cross the boulevard. The winding streets turn to cobblestone and widen. The buildings have balconies and terraces. Many are made of golden sandstone that reflects light. This is why I have come. This is what I imagined, just this: the color of the light reflected on the cobblestones and shimmering off the buildings. I breathe it in, and am guided to my destination by the sound of bells that resound through my body, harmonizing my soul with the soul of the Celestial.

The Basilica is the Middle Age's multi-media. Designed to overwhelm the senses with God's majesty, there are many domes painted with angels and gold. The old white man with the beard looks down from the center dome. Basilica St. Istvan's claim to fame is the possession of the right hand of its namesake saint. The charm of displaying the arm of a dead person escapes me, and frankly grosses me out. Obviously it bespeaks a very real cultural difference. It seems very Central European somehow.I wonder if someone could explain it to me.

Berne comes by and we go to a restaurant in the neighborhood, where we celebrate my arrival with Hungarian wine and an all goose dinner: appetizer of smoked goose and (minimal) salad, another appetizer of goose liver, followed by an entree of crispy goose leg with red cabbage, and a good bottle of Hungarian wine that tastes remarkably like pinot noir. I'm definitely not in Kansas---or Napa--anymore.

Day Three: Everything is open again after the holiday weekend. The streets bustle. Implementing my new "pleasure before business" plan, I decide to go first to the covered market before dealing with electronics and banking. The tram goes along the Danube, from whence I can see the hills of Buda, the houses of Parliament, and floating nightclubs and restaurants along with the tour boats. I note a jazz club and a Frank Sinatra piano bar. Alas, just as we approach the famous Elizabeth Bridge, the tram goes into a tunnel covered with graffiti, much like NY or Springfield MA, except it is in Hungarian. There is a certain comfort in not being able to read the words.

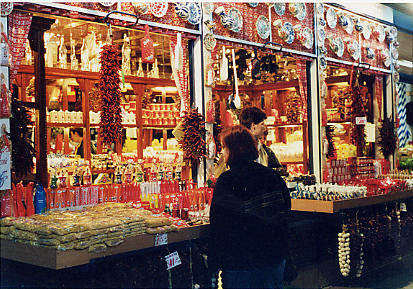

My reaction to the market is nothing less than ecstatic. Here are small stalls and shops run by individuals proud to sell fresh food. In the little stands are every kind of paprika and saffron, caviar, goose, duck, various meats and cheeses, dried porcini mushrooms, locally raised vegetables, all fresh.

I walk around the market with tears in my eyes, too happy to speak and unable to choose. A young man sees me looking stunned, and asks if I need help. He tells me about the local honey, Finally I find my way to the dairy shops and, with some help from a gentleman who speaks French, I purchase fresh churned butter, farmer cheese, goat kefir, and a smoked sheep cheese. Then I find lettuce, local asparagus, raw honey, coffee, eggs, a turkey cutlet for dinner, a bag of paprika and garlic to cook it with, and a couple of bottles of Hungarian wine recommended by my friend. I may become one of those European women who shops daily.

Shopping this way is a sensorially different experience from shopping in America, even at Whole Foods or the local coop. While I appreciate and am grateful for the proliferation of farmers' markets, somehow that is not the same, either.

Shopping in a market with food hanging on display everywhere, with smells and color that permeate the environment, turns the everyday task of shopping into a pleasure, rather than a chore. When something is a pleasure, we don't need to be in such a hurry. Life is right here, not someplace I have to get to. I remind myself that I can take as long as I want; it's OK to lollygag looking at all the different kinds of paprika or salami. In America we sort for efficiency. If it is more efficient, we think it is better, as if that were an end in itself. I have nothing against efficiency, when it is in the service of something greater. But it is a means, not an end. Efficiency is not sensual, fun, or enlightening. It is not beautiful. I do not want an efficient orgasm or an efficient dinner. Nor do I want an efficient life. I want a beautiful one.

The afternoon is spent on errands, and by evening I have my phone hooked up through the wonders of VOIP. I can communicate with clients and friends in the US as if I were still there. My local US VOIP numbers, hooked to my Internet router, ring here. Quite remarkable. If it were not for that availability, I could not afford to do this.

And yet... there is a part of me that misses getting lost, as one could when I first traveled Europe, and the only way anyone could find me was by sending a hopeful airmail letter on onion skin stationary to the closest American Express office. In those days travelers would arrive in a new city and go there directly, hoping for a word from home. In between, we were anonymous and un-moored. There was nothing to remind us of who we were or who we had been the day before. We were free to explore and invent, to discover ourselves in each moment. I could be anyone, as I wandered through the Plaka in Athens; I could be a CIA agent, an incognito movie star, a courtesan. Who knew?

One of the joys and the fears of travel -- not the kind that is safe and monitered so you never have to deal, but real travel -- is that existential moment of just casting yourself out onto the world. In that moment it is just you. It is immediate. You are nobody. Your identity and accomplishments are meaningless. There is only what you create and experience, without a buffer, without a net.