And why would you? The cover just grabs your attention and keeps out the dust (and the fleas). It takes only a moment to crack open the book and get a sense of whether the writing, the subject, or the plot is interesting to you.

Anybody who has more than one child or has tended a litter of pups can attest that there are huge variations in sibling personality and behavior.

And appearance -- when we see a mother dog with a litter of very different-looking puppies, we often assume there were different fathers. If you've ever seen street dogs breed, you know this can happen, but it's also possible to have extreme variation within a litter from the same stud and dam.

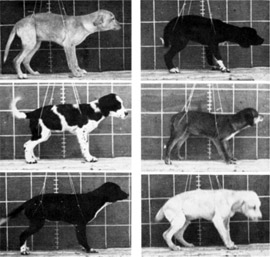

Look at these pictures, which come from well-known research in the 1960s. These pups are the second-generation cross of a cocker spaniel and a basenji. That's a lot of variation!

Look at these pictures, which come from well-known research in the 1960s. These pups are the second-generation cross of a cocker spaniel and a basenji. That's a lot of variation!

John Paul Scott and John L. Fuller published these photos as part of their studies of breed and behavior, Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog. They were trying to differentiate innate vs. learned behavior by comparing the behavior of generations of the cocker-basenji cross with that of purebreds of each breed. Ultimately they found that the parents' breed isn't a good predictor of the behavior of mixed-breed puppies.

Their conclusions were in line with what we know about the evolution of the modern dog:

Behavioral differences among breeds have often been regarded as remnants from past selection during the breeds' origin. However, the selection in many breeds has, during the last decades, gone through great changes, which could have influenced breed-typical behavior.

("Breed-Typical Behavior in Dogs--Historical Remnants or Recent Constructs?" by Kenth Svartberg, in Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 2005)

So instead of a dog being judged by its cover -- its superficial appearance -- research such as Svartberg's shows that its individual behavioral characteristics more closely follow those of its close relatives than traits associated with its breed.

Svartberg's study found that "basic dimensions of dog behavior can be changed when selection pressure changes, and that the domestication of the dog still is in progress." Dog breeders have known this for a long time and that's why we see "lines" within a breed: relatives who exhibit similar characteristics.

Everyone can think of such examples, and not just in animals: talents that run in families, personalities that seem "typical" of related individuals. Kind of like how people named Manning reign in the world of quarterbacking, or Kingsley and Martin Amis in literature.

Do genetics matter? Yes. Can we stereotype and predict across an entire breed or type? No.

For many years, dogs were bred with that same understanding: more for function, less for look. Today breeds are still categorized as working dogs (herding), hunting, and so on. But things have changed:

Historically, dog breeds were groups of dogs with similar behavioral characteristics, such as hunting or herding ability, and members of a breed did not necessarily resemble each other physically. Since the turn of the twentieth century, however, there has been a shift from purpose-based breeding to breeding on the basis of appearance.

("Rethinking dog breed identification in veterinary practice," by Robert John Simpson, Kathryn Jo Simpson, Ledy VanKavage, in Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, Nov. 2012 [download requires subscription])

Most dog shows are conformation shows: judges evaluate the contestants by how closely they compare to the official breed standard. The judges look at how a dog's form would fit its function, but not how it actually performs that function. (Events such as herding and field trials do test a dog's performance.)

And thus the gap widens between the cover and the contents.