By Rebecca Traister

In the first week of August, just as Hillary Clinton began to pull ahead significantly in the polls, Donald Trump prophylactically claimed that the only way he will lose in November is if Clinton cheats her way to victory. "I'm telling you, November 8, we'd better be careful, because that election is going to be rigged," Trump said. The next day he dug in further, suggesting that without stricter voter-ID laws, "people are going to walk in, they are going to vote ten times maybe."

Related: Hillary Is Poised to Make the 'Impossible Possible' -- for Herself and for Women in America

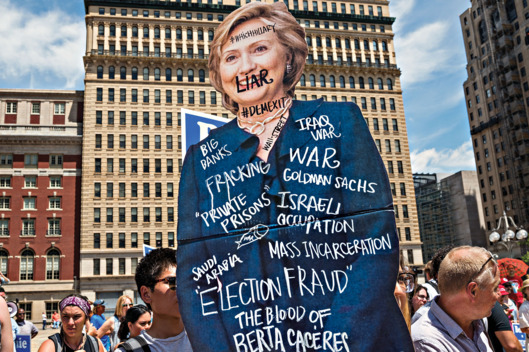

This idea of the system being rigged in Clinton's favor echoes recent rhetoric from the left. Some Bernie Sanders supporters spent portions of the Democratic convention accusing Clinton of having rigged the primaries -- a notion that was quickly picked up by the right: "Do you think the general election could be rigged?" Fox News' Sean Hannity asked in a tweet. But it was Trump's friend and sometime adviser Roger Stone who really bellied up to the bar, telling Milo Yiannopoulos that "this election will be illegitimate ... We will have a constitutional crisis, widespread civil disobedience, and the government will no longer be the government ... It will be a bloodbath."

While the blaming of an anticipated loss on voter fraud is certainly not exclusive to this election cycle -- Google "Diebold" and "2004" -- the language used by Trump and his allies, the language of delegitimization, is especially telling, and potentially powerful, in a race against the first woman ever nominated for the presidency. It channels a conviction that has deep roots in our culture: A woman could never really win, not over a man. Her purported victory must, on some level, be inauthentic -- whether because she cheated or because she shouldn't have been allowed to compete in the first place.

Not coincidentally, this was also the argument used in many attempts to delegitimize the presidency of our first black commander-in-chief. The "birther" movement -- led in part by Trump -- questioned Barack Obama's claim to the highest office in the land by suggesting that he was foreign-born, his very citizenship illegitimate. Even after Obama produced his birth certificate, questions about how real his electoral victory was persisted. In the brief period of Election Night 2012 in which it appeared that Obama might have won the electoral college but lost the popular vote, Trump tweeted furiously that his victory was false: "He lost the popular vote by a lot and won the election. We should have a revolution in this country!"; "The phoney electoral college made a laughing stock out of our nation. The loser one! [sic]"; "This election is a total sham and a travesty ..."

Now, surely Trump presents a particularly acute case of White Male Authority Dysfunction, but in his impulse to cry illegitimacy when faced with potential insurrection by a woman or a person of color, Trump is not un-American. In fact, it is a response that runs throughout our history.

Salamishah Tillet, professor of English and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania, argues that one of the first acts of delegitimization was a change in birthright laws designed to ensure that babies born to enslaved women and their owners could not be legitimized through their white fathers. In 1662, Virginia declared, in an inversion of European laws long based on patrilineal succession, that "all children borne in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother." Black citizenship, Tillet says, "is always something that has to be proven again and again and again," a reality made clear by the birther movement, which persists to this day.

Demanding proof of legitimacy is also central to the increased voting restrictions designed to throw voters of color off the rolls. A recent New York Times piece included the report that in Sparta, Georgia, the majority-white Board of Elections was "systematically questioning the registrations of more than 180 black ... citizens -- a fifth of the city's registered voters -- by dispatching deputies with summonses commanding them to appear in person to prove their residence or lose their voting rights." It's no accident that these voters made up Obama's base and are the ones most likely to vote for Clinton.

This disqualification of African-American civic legitimacy is linked to the history of American women's precarious hold on rights to full civic participation. Linda Kerber, historian at the University of Iowa, argues that this too goes back to the founding of the country. "When the framers make the nation in the name of free white men," she said, "you always need an other. You need boundaries. So the boundaries become Native Americans, who are dehumanized as savages; slaves, who are chattel; and women." Two hundred and forty years later, she says, you still "can't have a black man legitimately presiding over you, and you certainly can't have a woman directing you into battle."

Women's attempts to assert political authority were regularly regarded as unnatural and therefore illegitimate. Kerber cites Elihu Root, secretary of War under Theodore Roosevelt and winner of the 1912 Nobel Peace Prize, who said that women's suffrage would be "an injury to the state, and to every man and woman in the state ... Woman in strife becomes hard, harsh, unlovable, repulsive ..." Does this sound familiar?

Even after women won the vote, they were barred from serving on juries in many states, in part because the notion that women might be in a position of power over men -- deciding their guilt or innocence, determining their sentences -- was a perversion of the "natural" order. "The argument was: Could you imagine women on a jury sending a man to the electric chair?" says Kerber. (This was also the strain of argument deployed by some white suffragists after the suffrage and abolition movements were split by the enfranchisement of black men but not women of any color: "Think of Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a monarchy and a republic ... making laws for [white women]," Elizabeth Cady Stanton famously said.)

This line of thinking is so pervasive that it even crops up among some on the left who likely consider themselves feminists. "I don't cut the Bernie people any slack for what they're saying about it not being fair," Kerber says, noting that undergirding it is the conviction that "it's not right, it's not natural, that this woman could beat him. It's deeply rooted in assumptions that go back as far as the founding."

It's true that the major hit on Hillary Clinton has long been that she is untrustworthy, which makes it a short step to suggesting that her electoral victories are fraudulent. Surely some of this stems from a reputation and history particular to her. But it seems unlikely that Clinton is, by political standards, uniquely dishonest; former New York Times editor Jill Abramson has written of how her many journalistic investigations into Clintonian malfeasance revealed that Clinton was "fundamentally honest and trustworthy." The fact that "she can be so seamlessly rendered synonymous with all things untrue," says Tillet, is at least in part because "religious narratives tell us that women are inherently untrustworthy ... The idea of woman as a liar and as evil goes back to the Bible."

But the delegitimization of Clinton may also just be a primal, psychological reaction to the fear of being bested by someone who has been historically considered inferior, an attempt to restore the "natural order" -- or at least rationalize its temporary upheaval. Kerber pointed me to a recent piece in The New York Times Magazine, a profile of 19-year-old swimmer Katie Ledecky, that includes paragraphs on the experiences of the men Ledecky has swum against in practices. They speak of being "broken" by her, the victory of woman over man still an anomaly we associate with physical destruction. No wonder a presidential candidate currently polling below a female opponent is talking about how it is impossible for her to beat him fair and square. As one 17-year-old male swimmer said simply, "I'm not gonna lie, it can be annoying when she beats you ... You're just not used to getting beat by a girl."