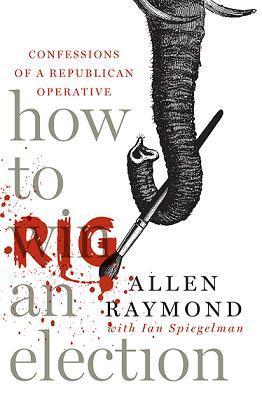

From HOW TO RIG AN ELECTION: Confessions of a Republican Operative:

The first sign of trouble at my sentencing hearing came when the judge cut off my lawyer in the middle of his statement.

"What about common sense!?" Judge Joseph DiClerico said, referring to me. "What about a personal moral compass?"

My lawyer had been making the point that I'd consulted an attorney before committing my crime, to ascertain if it was in fact a crime in the first place. That attorney, a legal advisor for the Republican Leadership Council — and before that the general counsel for the Federal Election Commission — hadn't thought so, but it obviously concerned him enough not to put it on paper. That didn't set off any alarm bells for me, however. Back in 2002, just about every

Republican operative was so dizzy with power that if you could find

two of us who could still tell the difference between politics and

crime, you could probably have rubbed us together for fire as well.

In GOP circles in 2002 it seemed preposterous that anything

you did to win an election could be considered a crime. For ten

years I'd been making phone calls with the intent to manipulate voters; hell, I'd been handsomely rewarded for it. In my business, communication devices were all lethal weapons — and every fight was

dirty.

The judge could prattle on all he wanted about my "moral compass" because he didn't understand that any compass that doesn't

lead a campaigner to victory is utterly useless in American electioneering. At worst, I saw my campaigning snafu in the New Hampshire general election as just some more political tomfoolery to cap

off a decade in which my party had gone from getting our asses

kicked out of Washington to treating all three branches of the federal government like our own personal amusement parks. It had

been no easy trick, but Bill Clinton had opened the door for us with

his '93 tax hike just after I'd gotten out of grad school with a master's

in political management. Who would have thought that we could

convince so many blue-collar workers that raising taxes primarily

on white-collar workers was intrinsically wicked enough that they

and other voters should give us both the House and the Senate? If

we could get elected by convincing our own hard-up constituents

that they were in the same boat as the rich, what wouldn't a voter believe? Those were heady times — and we were just getting started.

We spent the next eight years giving the truth such a furious

beating every time it showed its face that it eventually just stopped

coming around altogether. Candidates, voters, the press — no one

wanted anything to do with it. The reporters gave up asking serious

questions, the voters stopped reading past the headlines, and it was

a very cozy arrangement for everyone.

By the time I was working in presidential politics, a bunch of our

guys got together and pretty much stole the presidency. And the

voters? Hell, they were so offended that they actually voted to maintain our congressional majority in the 2002 election.

How could we commit a crime when we could do no wrong?

But my sentencing hearing was held in the winter of 2005, and

by then the country was starting to consider unfettered GOP rule

just a little bit disastrous. Even the guys who didn't expose undercover CIA operatives, proposition congressional pages, buddy up

with Enron, and send other people's children off to die in an impossible war wouldn't rat on the ones who did.

Everywhere you turned, so many Republicans were screwing

up so outrageously that even the press wasn't afraid of them anymore. When some GOP fixer--even in the White House itself--did

something wrong, reporters actually went ahead and put it on the

news just as if the Bush administration hadn't done everything it

could to stamp out any remaining traces of a free and open society.

Given the changes in the political climate, Judge DiClerico of the

United States District Court in New Hampshire certainly saw no

reason to be timid with the likes of me.

Until the judge tore into me, I had been thinking I'd get nothing

worse than a few months of home confinement, a bit of a break that

could be used to catch up on some relaxing little projects around the

house. From the second the FBI came to my door I'd done everything they wanted, connecting all the dots between the shady tactics

of the New Hampshire Republican Party during the John E. Sununu

Senate campaign, the Bushie who'd orchestrated the whole thing,

and me. The Department of Justice was getting ready to indict, because of my testimony, President George W. Bush's main political

guy in New En gland. The DOJ went so far as to argue that I should

be given the best possible treatment by the court for my exemplary

cooperation. Why wouldn't I have cooperated? After all, when the

shit hit the fan, my political party and my former colleagues not

only threw me under the bus but then blamed me for getting run

over.

After he finished with my lawyer, Judge DiClerico said, "I understand someone here wanted to make a statement."

Suddenly the chairman of the New Hampshire Democratic

Party, Kathy Sullivan, popped up and spoke from the gallery. "What

Mr. Raymond did was unforgivable," she said. "He assaulted democracy. It is a travesty that this could happen here at home, made

all the worse by the fact that Iraqi citizens just had their purple

thumbs in the air in triumph for having had their first free election."

The argument lacked reason, sure, but it was brimming with the

broken bones, missing limbs, and body bags that give politics flavor when substance is in short supply. She did everything but glue a

beard to my face and call me Saddam.

That would have been bad enough, but the judge followed up

by calling on the most damning speaker of all. "Would the defendant like to address the court?"

Now I was truly screwed. I'd been given no warning that I'd be

expected to speak, so I had nothing prepared. All of my political

training dictated that you spend as much time as possible preparing

for any eventuality and that there was only one thing to do if you

were ever caught off guard: bullshit them.

But in the three years between my crime and my sentencing, all

the bullshit had been thoroughly knocked out of me. My old pals at

the Republican National Committee were spending almost $3 million on my co-conspirator's legal defense because he was still a loyal

member of the GOP family, while at the same time labeling me a

liar, a rogue, and a thief to any news outlet that would listen. From

former bosses to business partners, colleagues to clients, the Party

Elite couldn't lie about me fast enough, and they didn't send a dime

of Republican defense money my way even though I'd served the

cause for its entire glorious decade, from the Contract with America

to taking back the White House.

What was I going to say? "You can't trust these guys — I should

know, I used to work with them!" The idea of spinning my own

trial — the idea of spinning anything ever again — made me feel sick.

For both the Democrats and the Republicans, this trial, my trial, was

merely another campaign. But it was my reputation, my family, my

life.

The experience left me a spirited proponent of the truth.

Standing there, withering under the judge's glare, all I could

think of was being a little kid and having my mother tell me that

when you did something bad, you had to apologize.

"Your Honor," I said, "I did a bad thing."

He looked at me like I was just giving him more of the spin my

indictment had generated in the press, like I was still the same full-of-shit GOP operative I'd been since I first hit the ground politically.

But this was me, to the bone, and maybe that was the saddest part.

After a decade of slashing and burning my way up the ranks of

American politics to become a high-level Republican Party campaign op and then a highly compensated Republican political consultant, I stood in that courtroom in all of my natural glory: a

privileged, newly minted felon who had spent a career carefully

massaging ideas into messages but who now couldn't string together

a couple of coherent sentences.

I tried again.

"It was a terrible endeavor to undertake. While what I did was

outside of my character, I take full responsibility for those actions. I

apologize to the court and to the people of New Hampshire."

In the next national election cycle, Republicans would be apologizing to towns and cities and states all across America, but for the

first time in thirteen years I'd have nothing to do with who won

those elections. After serving out the sentence the judge was about

to impose on me, I wouldn't even be allowed to vote.

From HOW TO RIG AN ELECTION: Confessions of a Republican Operative by Allen Raymond with Ian Spiegelman. Copyright 2008 by Allen Raymond. To be published January 2008 from Simon and Schuster. Reprinted by permission.

Read author Ian Spiegelman's piece on the Huffington Post, "If You Can't Vote for Anyone, You Can Always Vote Against Someone: How I Learned to Quit Whining and Get Involved"