WARNER ROBINS, Ga. — The Rev. Raphael Warnock has been through this before. A few times, actually. And quite recently.

“In the course of the past two years, between primaries, general elections and runoffs, this will be the fifth time my name has been on the ballot,” Warnock told a crowd of military retirees and union members outside the headquarters of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 987, which represents non-military workers at the massive Robins Air Force Base. “Each of the first four times, I finished first. And I’m going to finish first again.”

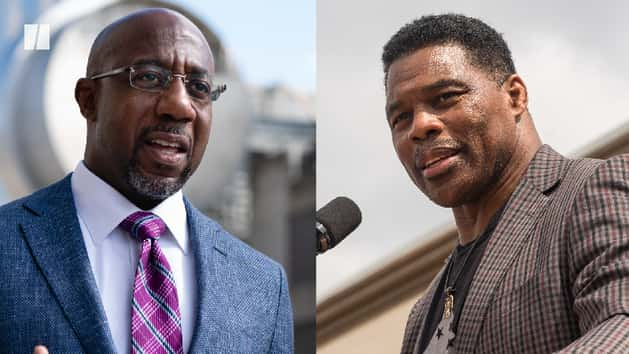

Warnock, Georgia’s incumbent Democratic senator, is facing a Dec. 6 runoff election against GOP nominee and University of Georgia football legend Herschel Walker. Peach State voters, who may be tired of nearly three straight years of attack ads, have seen this all before.

This runoff, however, is taking place in a drastically different political environment than the one Warnock and Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-Ga.) triumphed in two years ago, handing Democrats a majority in the Senate.

The apocalyptic rhetoric the GOP deployed then has faded, replaced by efforts to portray Warnock as just another political hack. A Republican-led overhaul of Georgia’s voter laws has created additional confusion and cut the time to campaign for the runoff in half. And compared to 2020’s all-base-all-the-time faceoff, both Democrats and Republicans are still working to persuade the critical slice of the electorate that backed both Warnock and Georgia GOP Gov. Brian Kemp in the first round of voting.

Warnock, having led Walker by about a single percentage point in the first round of voting, is a slight favorite in the runoff. The first public survey of the contest, conducted by a bipartisan duo of pollsters and released by AARP’s Georgia chapter, found the incumbent with a 51% to 47% edge over Walker.

Warnock’s edge, in both polling and in the first round of voting, was built on a delicate balance of wooing independent voters and turning out Black voters. The first was an unqualified success in Round 1, the second a mixed bag, with rural Black turnout lagging. Republicans, however, are going after both in hope of denying Warnock a full term.

From Threat To Hack

As Warnock spoke in Warner Robins, a van with electronic billboards paid for by Walker’s campaign circled the event. It blared two messages: “BELIEVE ALL WOMEN, BUT NOT YOUR WIFE?” and “SLUMLORD MILLIONAIRE.”

The truck neatly illustrated how GOP attacks on Warnock have shifted. Two years ago, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene called Warnock a “heretic” for supporting abortion rights. GOP ads suggested he was a Communist. A cavalcade of Republicans warned victories for Warnock and Ossoff would lead to the collapse of the First and Second Amendments to the Constitution.

While the apocalyptic rhetoric has not disappeared entirely, much of it has been replaced by efforts to instead portray Warnock as a disposable politician, someone who engages in the same self-enrichment and hypocrisy voters have come to expect from a member of Congress.

“He paid himself for child care, all that stuff — why don’t he keep his own kids? Don’t have nobody keep your kids,” Walker said at a campaign stop earlier this month, criticizing Warnock for using campaign funds to pay for a nanny for his children — a step that is entirely legal. (There’s also the matter of Walker having multiple children whose lives he has played minimal roles in, but we digress.)

The more potent version of this attack has focused on the conditions and treatment of residents at a housing complex owned by the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Warnock remains head pastor and where civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was co-pastor at the time of his assassination. The church gives Warnock a $89,000-a-year housing allowance, while some residents of the housing complex have received eviction notices — though none have actually been evicted so far.

Both Walker’s campaign and outside Republican groups have aired ads attacking Warnock on the issue, with one featuring a Vietnam War veteran threatened with eviction saying he could lose his apartments over $119. Talking to reporters after an event in Macon, Warnock was terse when discussing the issue.

“I’m proud of the work that my church does to feed and house the hungry,” Warnock said. “I don’t think anyone is surprised that Herschel Walker continues to lie.”

While these attacks can damage Warnock’s image with swing voters, they also look to tap into the cynicism many Black voters feel about politics. While those voters are unlikely to back Walker, they could stay home, Democrats warn, even as they note their internal polls show Black voters remain sufficiently engaged.

Warnock is a historic figure: When he was born in 1969, both of Georgia’s senators were avowed segregationists, and he’s the first Black Democrat elected to the Senate in the South since the passage of the Voting Rights Act. But combating the cynicism Republicans aim to engender about him requires regularly sounding like a more traditional pork-barrel politician.

In Macon, it meant the city’s mayor pro tem emphasizing how the American Rescue Plan, which Warnock voted for, helped the city hire more police officers. In Warner Robins, it meant talking about how he worked with Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) to help get money to widen a highway connecting military bases in Texas to those in Georgia.

“I’ll work with Ted Cruz for 15 minutes if it helps the people of Georgia,” Warnock said.

From Motivation To Persuasion

In 2020, the two Senate runoffs were entirely focused on motivating the party’s respective bases, with each party pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into field operations to reach voters during the heart of the coronavirus pandemic.

In 2022, persuasion is as big a part of the equation. At the center of it are the thousands of Georgians who split their ballots between reelecting GOP Gov. Brian Kemp by seven percentage points and giving Warnock a 1-point edge over Walker in the Senate race. Winning at least a portion of these voters back is critical to any chance Walker has. And what better messenger to reach them than Kemp himself?

“Herschel Walker will vote for Georgia, not be another rubber stamp for Joe Biden,” Kemp says in the 30-second ad paid for by Senate Leadership Fund, a super PAC controlled by allies of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. The super PAC has also transferred millions of dollars to Kemp’s political operation to keep the field operation he ran during the general election alive during the runoff.

Warnock has countered with his own ads and events highlighting his backing from Kemp supporters — something the campaign was reluctant to do during the general election when Democratic nominee Stacey Abrams was still on the ballot. On the same day Walker and Kemp campaigned together earlier this month, Warnock held a counter-event where Kemp supporters explained why they were backing him.

“The more I heard about Herschel Walker, the more I became concerned about his honesty, his hypocrisy, his ability to lead,” a woman named Lynn says in one of Warnock’s ads after saying she was “proud” to vote for Kemp. “At the end of the day, I have to vote for someone I can trust and that has integrity. And I don’t believe that is Herschel Walker.”

Some internal Republican polling of the race has found the two parties tied on measures of enthusiasm, a bad sign considering Walker trailed Warnock during the November election despite Republicans being more fired up. The GOP had long feared Walker’s personal failings would make it difficult to turn out voters for him if control of the Senate was no longer on the line.

Democrats’ ability to defend incumbent senators in New Hampshire, Nevada and Arizona, while picking up a GOP-held seat in Pennsylvania, has made that scenario a reality.

If Warnock wins, Democrats will have a 51-seat majority in the Senate, which would actually grant them substantially more power than their existing 50-seat majority, including the ability to issue subpoenas without GOP sign-off and a free hand to quickly move nominees. But that’s far less of an enticement for voters than the $2,000 checks Democrats were able to promise if they won in 2020.

From Slog To Sprint

When the field team from the New Georgia Project Action Fund knocked on the door of the single-story brick house in South Atlanta with a wrecked Dodge Ram 1500 out front, they got a response they were prepared for.

“We just voted!” an older man told the organizers, clad in neon yellow shirts with the type “OUR VOTE. OUR RIGHT. OUR MIGHT.” They explained to him the runoff was on Dec. 6, and helped him make a plan for how to get to his polling place to vote early.

Compared to the two-month-long slog of 2020, the Nov. 8-to-Dec. 6 turnaround for this year’s runoffs is a taxing sprint. The group, which functions as the political arm of the nonprofit founded by Abrams to turn out Black and progressive voters in the state, gave its organizers just two days off after Election Day. They took a lone day off for Thanksgiving, and were back knocking on doors on Black Friday. (The organizers were paid time-and-a-half.)

The lack of a precedent for this election — beyond the time frame, the rules are also different — means both parties are struggling to glean much information from early voting. While turnout among Democratic-leaning demographic groups and counties has encouraged party operatives, Republicans are expected to dominate Election Day voting.

But the timeline switch, which was mandated by Republicans’ 2021 law overhauling the state’s elections in the wake of President Donald Trump’s rampant lying about voter fraud, has also generated significant voter confusion: Many counties in the state were unsure or unclear on when they would send out mail ballots, and the state initially said there would be no early voting on the Saturday after Thanksgiving. After Democrats sued, the state Supreme Court ruled voting could take place.

“There’s a lot of confusion going on right now. The timeline’s been shortened,” said Simran Jadavji, a New Georgia Project Action Fund spokeswoman who expressed frustration with the idea — popularized by Republicans who backed the law and some in the national media — that relatively high turnout in Georgia’s elections meant the voting overhaul did not suppress votes. “Absentee ballots are not as reliable this time around.”

The impact of that shortened timeline was visible on Tuesday and Wednesday of this week, when roughly one-third of the early voting centers in Fulton County — which contains most of the city of Atlanta and is a key county for Democrats — reported wait times of more than an hour, with some reporting wait times of over two hours.

“People are living busy lives,” said James Mays, the New Georgia Project’s deputy field director. “People are working multiple jobs, trying to take care of their kids. I think people getting caught up in day-to-day living is the biggest hurdle we face right now. That’s the reason we have to be out here.”